This is a weekly wrap that isn't really like a weekly wrap — it's a chonky issue mainly focused on one story. There was just so much detail I wanted to include that I couldn't condense it into a single section.

“Think you’re having a bad day? Trust us, it could be worse.”

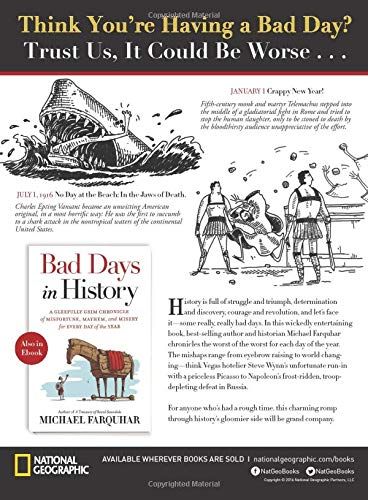

These words, muttered on a Zoom call, came through the speakers in the courtroom. Those of us sitting in the public gallery burst into laughter, just from the sheer absurdity of the situation. I worked out that the voice belonged to Pannir Selvam, reading from a page in an issue of National Geographic that he was holding up to the webcam and showing to his friends.

The context was too surreal. Taken alone, those two lines were just a catchy pitch for a book on historical misfortunes. Spoken by Pannir, a death row prisoner — while he was dialled into a Zoom hearing at the Court of Appeal with 23 other men with death sentences, waiting for the judges to return with a verdict on their appeal — the words took on a whole new meaning.

Devastatingly, the day (or, by that point, the night) did get worse.

The originating claim

There were so many little rectangles on the screen on Thursday afternoon: Supreme Court staff, court interpreters, three prosecutors from the Attorney-General’s Chambers, three Court of Appeal judges, and 24 death row prisoners calling in from Changi Prison. We could see them on the multiple screens spread across the Court of Appeal, where we were gathered to watch the Zoom hearing. Writing it out like this, it almost sounds like a ridiculous set-up for a reality TV show. But the stakes couldn’t have been higher for the 24 inmates on Thursday: if they succeeded in this appeal, Abdul Rahim bin Shapiee (plaintiff #2) would be spared the noose the next morning, and they would all be safe from the gallows as long as the case was pending.

The application at the centre of the hearing spoke to a long-standing frustration of death row prisoners and their families; namely, the struggle to get legal representation post-appeal. While people charged with with capital offences can get lawyers appointed for them under the Legal Aid Scheme for Capital Offences (LASCO) at the trial and appeal stage, things are different post-appeal. The threshold for seeking a review is very high, and, since Kho Jabing’s case in 2016, I’ve seen late-stage applications get labelled as “abuse of process”. Recently, we’ve also seen lawyers get slapped with hefty cost orders for applications deemed an abuse of court process. Both activists and the families of people on death row have found it increasingly difficult to persuade lawyers to take on late-stage applications, and lawyers have brought up the fear of having to pay cost orders as a disincentive to get involved in late-stage cases.

The 24 prisoners pointed to these troubles in their originating claim, arguing that the Attorney-General’s Chambers’ habit of seeking cost orders had created a chilling effect that made it more difficult for them to get legal representation, thus undermining their right to access to justice.

Case in point: they couldn’t find a lawyer to represent them in this application, and could only file it through the prison and represent themselves. This wasn’t an easy thing to do. They’d wanted to file the application on 28 July, but weren’t able to because the prison said they had to find out the specific documentation needed to file such applications, and how much such a filing would cost, themselves. (In a press statement, the Singapore Prison Service asserted that while their staff are familiar with filing criminal motions and judicial review applications, the civil suit that the prisoners wanted to file was a “non-routine application”.) After some effort, the application was finally filed in the afternoon of 1 August, costing $717.60.

But there was one serious problem: between 28 July and 1 August, Rahim had been issued an execution notice, informing him and his loved ones that he would be hanged on 5 August.

Proceeding at breakneck speed

With the clock ticking for Rahim, the application, once filed, proceeded at a breathless pace. Such civil suits usually take weeks and months, likely involving applications, submissions, affidavits, reply affidavits, and multiple case conferences. For the death row prisoners, though, it all happened in four days:

- After the application was filed on 1 August, a case conference was scheduled for 10am the next day.

- At the case conference on 2 August, the AGC indicated that they would apply for the prisoners’ application to be struck out in its entirety. Both sides were told to file submissions by 6pm the same day. A hearing was fixed for the next morning.

- On 3 August, the prisoners had to argue their case, in chambers (i.e. not open to the public), at the High Court. A verdict was delivered that afternoon, ruling in the AGC’s favour. Although the judge granted Rahim an interim stay of execution that would remain in place until after the appeal, the appeal hearing itself was fixed for the next afternoon. If the appeal was dismissed on the same day, the interim stay would no longer be in effect, and the prison would be able to hang Rahim on 5 August as planned.

Addressing three Court of Appeal judges — Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, Justice Tay Yong Kwang and Justice Woo Bih Li — on Thursday afternoon, Iskandar bin Rahmat, speaking on behalf of all his fellow inmates, said that this expedited timeline had put the prisoners in an impossible position. The statement of claim that they’d filed, which the High Court judge had criticised for being too broad, had only meant to set out the main points that they were relying on, with the intention that they’d fill in the details as the case progressed. They’d planned to do this by following up on the originating claim with more supporting documents and evidence, such as affidavits from friends and family members recounting the difficulties they’d faced.

These plans went out the window with the sped-up process. The prisoners didn’t have a lawyer, and even though some of them have done a lot of reading over the years, none are actually legally trained. They live in solitary cells, with very limited access to the outside world. They needed the help of relatives — who can more easily look up information, or find people who might have the answers — to prepare, but visiting days are usually only Saturdays or Mondays, which meant none of them had been able to meet their families since the application was filed. The only person who could receive family visits was Rahim, because family members are allowed to visit daily in the seven days leading up to the execution. (If not for Rahim’s family visits, those of us outside wouldn’t even have found out about the extremely tight deadline that the prisoners had been given at the case conference on Tuesday.)

“We were caught off-guard and totally unprepared to prepare for such an urgent hearing,” Iskandar told the court. “This has cost us our right to a fair hearing.”

Datchinamurthy a/l Kataiah — who’d represented himself back in April after the authorities issued him an execution notice while he was still party to a civil suit, and won a stay of execution — added more details about the obstacles in their path. Before their appeal hearing, Datch had asked the prison officers for permission to meet Iskandar so that they could discuss and prepare for the case together. His request was rejected.

Both Iskandar and Datch were of the view that the prison’s actions — asking the prisoners to find out the requirements for filing their application themselves, and the refusal to allow them to meet — stemmed from a desire to keep to the execution schedule that had been set. “To me, the only reason the prison [refused my request] is because they don’t want the court decision to become favourable to us, so they can proceed with the execution on Friday,” Datch told the court. He said he didn’t know where else he could air this grievance.

“I feel like prisons are so desperate to execute us, and are putting us in a difficult state,” he said. “I want the court and public to know that we as death row inmates are not being treated fairly when we are fighting to prepare our case to fight for our lives… I hope the court will look into this.”

In response to Datch’s allegations, the Chief Justice said that the court is not in a position to give the prison directions, unless application is filed and a matter brought before the court. When Datch asked how he could file the application, CJ Menon told him that he couldn’t give legal advice, and that he had already given Datch the courtesy of listening to what he had to say even if it wasn’t relevant to the case at hand.

In response to the inmates, the prosecution denied that the prison had delayed their application on purpose, saying the fact that Rahim had received an execution notice in the interim had been "pure coincidence".

The prosecution also argued that there was a difference between access to legal advice and getting legal representation. They said that death row prisoners are able to ask to see lawyers, and that lawyers can go into prison to meet them. Prisoners are also allowed to meet and talk to their families, who can assist them. (Oddly, activists were also brought up as people death row prisoners could get help from, even though activists have no access to prison and can't actually meet the inmates.)

The prosecution even went as far as to say that the fact that the 24 were able to appear in court to argue their own case was proof that there was equal access to justice, and that they had suffered "no prejudice" even without legal representation.

Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin, a prisoner who had almost been executed in 2020, pushed back on the prosecution's points. "As a layperson, access to a lawyer, to me that is being represented. That is when I believe [when I think of] access to legal counsel'," he told the court. He also pointed out that visitation rules tend to only allow immediate family members, which means he can't meet friends or activists who might be able to assist him with his case.

Rahim’s individual application

During the hearing, the court was also informed that Rahim had filed a claim against his trial lawyer, alleging that the lawyer had not followed his instructions to call the woman who had been arrested with him as a witness in his defence. A case conference had been fixed for 1 September.

Speaking through a court interpreter, Rahim asked the court for a stay of execution. He said that he had new evidence, in the form a witness, that he wanted to put before the court. He’d asked his trial lawyer to call on this person during the trial, but the lawyer hadn’t done so, and had also told Rahim’s younger sister that switching lawyers would complicate the trial. He told the court that, if only they granted him a stay of execution, his family could find him a lawyer to handle the claim that he’d filed.

Treating Rahim’s request as an oral application separate to the joint appeal, CJ Menon began asking him about who this new witness was, whether he’d mentioned his unhappiness to his trial lawyer, why he hadn’t brought it up with his appeal lawyer, why he hadn’t said anything earlier, etc. Honestly, though, I didn’t think that was what Rahim had intended; it seemed to me that all he wanted to tell the court was that he hoped they could allow him a stay so that he could live to see the claim he’d filed proceed on its own timelines (with the case conference on 1 September being the first step). He certainly hadn’t been prepared to suddenly have to argue the merits of a formal stay application right there and then.

Hanging out on Zoom

The court stood down around 5pm for the judges to deliberate and come to a decision. For Zoom hearings, appellants tend to get put into the waiting room during this time. But given how many appellants there were in this case, and how long it had taken to check their connections, audio quality, and that they were linked to interpreters, it was decided that the prisoners would get to stay on the call, while the judges would move into the waiting room.

Thus began the death row Zoom social.

There’s still a lot about conditions on death row that we don’t know, or don’t have a clear picture of, but I think it’s safe to say that it is extremely rare for so many death row prisoners to be able to be in the same space (albeit virtually). They weren’t going to let this opportunity go to waste, and the Zoom meeting room that had been so solemn and serious quickly turned into a chat room where friends — some of whom might have been moved into cells further away from one another, depriving them of the ability to easily communicate with one another — discussed the proceedings, teased one another, cracked jokes, chatted, and shared how much they missed those who’d already been executed. For a long time, the virtual meeting room buzzed with conversations in Malay and Tamil, and most strikingly, with laughter.

It was heart-warming to see them enjoy one another's company. But it was heart-wrenching too, watching that screen, listening to the chatter, witnessing how full of life that online space was, while knowing that the state intends to eventually kill every single one of them.

A seven-hour wait

The judges were supposed to return with their decision at 7:30pm. But they didn’t.

At about 8:50pm, we were told that it would take another 20 minutes or so. But they didn’t come back then, either.

In the courtroom, we were still watching and — for those who could understand either Malay or Tamil — listening in to the conversations that the prisoners were having, until they were told to turn off their cameras. After that, the only person left onscreen was one of the Malay interpreters; an older man who we proceeded to watch as he prayed and waited. And waited. And waited some more.

As the hours crept by and it approached 11pm, a friend also sitting in the public gallery with me wondered out loud if perhaps court had adjourned for the day and the judges had gone home, and they'd just forgotten to tell us. But surely they would have told the interpreter? And so we stayed put.

Over at Changi Prison, Rahim’s family were waiting anxiously for news, every minute shredding their nerves. (Because the inmates were all on standby on Zoom, they were also losing precious visitation time with Rahim.) Relatives of other death row prisoners, past and present, were sending WhatsApp messages too. “Any update?” “Are the judges back yet?” “What’s happening?” Nervousness battled with exasperation as time passed.

In the end, the judges returned at 11:55pm — seven hours after court stood down.

“Having a bad day? Trust us, it could be worse.”

The Court of Appeal upheld the High Court’s decision to strike out the prisoners’ originating claim.

They ruled that even if the AGC seeks cost orders, it’s still the court that decides whether or not to impose them — something that they’re empowered to do under the law. They said that, when cost orders were imposed, there were grounds of decision making it clear why they were imposed, and that a “high threshold” exists for giving lawyers such fines. They drew a distinction between cases that turned out to be “weak on its merits”, which would not be subject to cost orders, and cases that were “unmeritorious”, which would be. (How lawyers will parse this difference while deciding whether or not to take on a case, I am not sure.)

Although the 24 prisoners were saying that it was their lived experience that it was difficult to get post-appeal legal representation, and that lawyers were scared off by the spectre of cost orders, the Court of Appeal ruled that any “reasonable” counsel would not refuse cases that had merit. If the inmates had trouble finding lawyers, they said, and if those lawyers were citing cost orders as the reason for staying away, then those lawyers were either misunderstanding how cost orders are awarded, or they'd felt that the applications the prisoner wanted to file had no merit and would therefore attract cost orders they wanted to avoid (which would mean that the provisions were working as intended). The Court of Appeal ruled that there was no legal basis for the 24 death row prisoners’ arguments in their application.

Rahim’s request for a stay of execution, too, was denied. The court determined that the civil suit against his trial lawyer had been an “afterthought”, since he hadn’t brought up his complaint earlier, particularly at the appeal stage. Without the stay, Rahim’s execution could go ahead as planned.

“I just want to rest”

Between the court hearing and the highly unusual — likely even unprecedented — long wait for the judges to return, Rahim spent the last afternoon, and a large chunk of the last night, of his life sitting on a Zoom call, only for it to all come to nothing.

As CJ Menon read out the court’s grounds of decision, and it became clear that things were not going his way, Rahim sat slumped with his arms crossed on the desk, his head buried in his arms. After the court session ended at 12:40am on the day of his scheduled execution, he was allowed to see his family one last time for about an hour. It was about 2am by the time their visited ended; by then, he had only four hours left to live. He told his family that, because of the seven-hour wait, he hadn’t had his last meal.

Rahim had tried to speak up for himself in court, but hadn’t succeeded. His case was closed. He felt that he had come to the end of the road. “I just want to rest,” he told his sister. He thanked her for everything she’d done for him, and told her to convey his gratitude to everyone outside prison who’d tried to help. He told her he was sorry for the trouble he’d caused everyone.

At around 6am, on 5 August 2022, Abdul Rahim bin Shapiee and his co-accused, Ong Seow Ping, were taken from their cells and executed.

Thank you for reading. Feel free to share this widely.