This longread was written in collaboration with The Initium《端傳媒》, who has published the Traditional Chinese version. You can become a member of The Initium and support their longform journalism here.

I’ve been informed by Substack that this piece might be truncated by Gmail because it exceeds their usual email size — you can click a link when you reach the bottom to read it in its entirety in Gmail, or read it in your web browser. Sorry about this, but it didn’t make sense to me to break a story into two emails!

A Perfect Storm for an Outbreak

By Kirsten Han

“They’ve contained the coronavirus. Here’s how,” read the New York Times headline on a piece about best responses to COVID-19. Alongside Hong Kong and Taiwan, Singapore was held up as a model for the rest of the world.

That was March 13, when Singapore had 200 confirmed cases of COVID-19. It’s a wildly different situation now. As of the time of writing, Singapore has confirmed 11,178 cases of the coronavirus.

The main reason for this skyrocketing figure has been the discovery of the virus spreading like wildfire within dormitories housing migrant workers. Over 80% of the country’s COVID-19 cases are migrant workers living in dormitories. In the dormitory with the largest cluster thus far, over 15% of the population of 13,000 men have tested positive. The resulting scramble to contain this tsunami of infections has highlighted uncomfortable truths about the city-state’s treatment of the men who built it.

Dormitories on lockdown

Sungei Tengah Lodge, on the western side of Singapore, looked tranquil from a distance on a late Saturday afternoon. But things were far from normal. On April 9, two blocks in the 10-block complex were gazetted by the government under the Infectious Diseases Act as an “isolation area”; the remaining eight blocks were gazetted the following day.

Two days after the initial lockdown order, men in surgical masks stood at the main gate, blocking unauthorised entry. But even from the outside, I could hear, and feel, a faint hum in the air — the hum of about 24,000 men shut in with nothing to do.

The men living in Sungei Tengah Lodge are only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of workers, mostly from countries like Bangladesh, India, and China, who have come to Singapore to fill a range of supposedly “low-skilled” jobs, from cleaning to construction work. If one includes female domestic workers — who are required by law to live in their employers’ homes — the number of migrant workers in the city-state number almost one million, or close to a fifth of the country’s population.

About 200,000 male migrant workers live in purpose-built dormitories — campuses, run by private operators, that also contain canteens, minimarts, and recreational facilities. Others live in former industrial buildings that have been converted for habitation, and still others stay in temporary lodgings on their work sites, or privately rented accommodation.

On April 5, the first two dormitories — housing 13,000 and 6,800 men respectively — were declared isolation areas under the law. Others, including Sungei Tengah Lodge, were soon added to the list. As of the time of writing, 21 dormitories have been gazetted, their inhabitants confined to their rooms. All other purpose-built and factory-converted dormitories have also been placed on lockdown. These drastic moves have restricted the movement of 323,000 men, while other construction workers not living in dormitories have been told to serve 14-day stay-home notices.

A press release from the Ministry of Manpower issued on April 11 claimed that “[safe] distancing measures have been implemented at dormitories gazetted as isolation areas. Dormitory residents are required to stay in their rooms and only leave their rooms to collect food and other supplies, or to use the washroom.”

But that afternoon at Sungei Tengah Lodge, men were standing in corridors or mingling in stairwells. From outside, I could look in through the wide open windows to see fluorescent strips of light flickering in rooms as ceiling fans whirred. It was clear that safe distancing — maintaining a distance of at least one metre from another person — wasn’t being practiced.

One can’t blame the men; while safe distancing has been widely recommended as a way to reduce transmission, it’s simply not feasible in an environment constructed specifically to house a maximum number of people in a (legal) minimum amount of space.

Under Singapore’s regulations, the living space standard for each person in a dormitory is 4.5 square metres, including facilities such as “living quarters, kitchen, dining, and toilet areas”. According to migrant labour rights group Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), a typical purpose-built dormitory room houses about 12 to 20 men sleeping in bunk beds. Hanging one’s clothes, towels, or damp laundry across the bunk is often the closest a man can get to privacy. With no air-conditioning in a humid tropical country where temperatures hover around 30˚C, sitting in a room with so many others is stifling.

A segregated population

It was February 8 when the first migrant worker was confirmed to have the coronavirus. He was case 42, in the early days when Singapore was keeping a lid on the spread. His work site eventually saw a cluster of five cases. The real estate company behind the project told the media that it shut down the site for cleaning and disinfection, and cooperated with the authorities for contact tracing. In response to reports of workers from his dormitory being turned away from work, the Ministry of Manpower reassured employers that his close contacts — 19 people in all — had been issued quarantine orders.

Speaking to the press on April 14, Minister for Manpower Josephine Teo said that cases of migrant workers testing positive for COVID-19 in mid-March had been “few and far between”. She explained that epidemiologists found that infected workers had been linked via common work sites, or socialising within their dormitories and on their weekly day off.

On an average Sunday before the outbreak, Singapore’s Little India district would have been chock-a-block. South Asian migrant workers gravitate towards that area on their rest day, because it’s where they can do their shopping for prices much lower than at the malls that Singaporeans prefer to frequent. Little India also provides a space for them to meet up with friends, grab a meal that tastes a bit more like food from back home, or send money to their families.

These regular social activities weren’t always well-received by Singaporeans or other residents, who complained about groups of workers hanging out near or in their neighbourhood estates. In 2016, a member of parliament was forced to apologise after referring to crowds of migrant workers as “walking time bombs and public disorder incidents waiting to happen”. Earlier this month, the former minister for communications and information also had to apologise for a Facebook post that included the comment “[but] it takes a virus to empty the space” when commenting on the way migrant workers used to congregate within his constituency. Surveillance and policing in Little India has been observed as operating on “the assumption that migrant men are a threat to public order”.

This forms part of the context within which COVID-19 made its way into the migrant worker population: brought to Singapore to do work that locals refuse to undertake (at that rate of pay, anyway), migrant labourers aren’t only housed separately from the rest of the population, but also perceived and treated differently. The spread of the virus through close contact at work, in dormitories, and common areas for socialising — such as Mustafa Centre, a popular 24-hour shopping centre in Little India — is also enabled by the fact that spaces in which workers are able to congregate have been limited from the outset.

Debbie Fordyce, TWC2’s president, tells me that the long-standing segregation of migrant workers affected the COVID-19 response, too: “In keeping with the attitude that we’ve always felt has been directed to migrant workers... [they’re treated as] a whole different category, almost as if they’re a whole different species of animal, so they matter in a different way.”

In the early stages of the outbreak, the Singapore government was proactive in putting out advisories, urging Singaporeans to step up hand-washing, and to seek medical attention if unwell. Temperature checks and contact tracing registration sheets popped up across the island, and Singaporeans complied with these requirements without much fuss.

But Fordyce says that these measures weren’t quite as well communicated to the workers. “They were aware of this, but they weren’t being asked to do anything differently,” she says.

When safe distancing isn’t possible

In March, Zakir Hossain Khokan was still working on a construction site as a supervisor. The 41-year-old Bangladeshi, a former journalist, has been in Singapore since 2003. As a poet, he’s won the Migrant Worker Poetry Competition more than once, and has given talks at schools and literary events. In a country where the space for migrant workers to speak for themselves is extremely limited, Zakir recently founded Singapore’s first migrant literature festival.

When asked back in March how migrant workers were coping with the coronavirus outbreak, Zakir said that temperature screening had been implemented at his site, and workers urged to see a doctor if unwell. The men were also regularly briefed at work on hygiene and safe distancing.

But he noted that safe distancing just wasn’t possible a lot of the time. While the men kept a metre away from one another while queuing for the bus, they were still sitting side-by-side in the bus. The same applied at their lodgings; workers would maintain distance while waiting to scan their resident cards, but were still living in close quarters and sharing communal facilities once inside.

Safe distancing isn’t the only problem. Even in “normal times” migrant workers exist in extremely precarious conditions: their work permits are tied to their employers, who are allowed to cancel them at any time, with or without reason. When so many have taken loans, pawned possessions, or leased family land to raise the thousands of dollars needed for recruitment fees, the threat of repatriation is a huge disincentive to speak out, complain, or do anything that might run the risk of displeasing their bosses.

Fordyce points out that this long-standing problem is likely also a factor in the coronavirus spread. The official advice might have been to stay home and seek medical attention if unwell, but it was unlikely any migrant worker would have heeded such a call if they feared the consequences of taking sick leave. Some employers have even been known to impose fines if men fail to show up for work.

While the government might have been concerned about the disruption of shutting down work sites, workers were worried about losing their jobs if they asked for time off. “In the minds of both, it was the economy,” Fordyce says.

What was being created — from the crowded conditions in the dormitories and the inability to maintain safe distancing, to the lack of adequate labour protections that left workers too afraid to report sick — was a perfect storm for an outbreak.

“Two separate categories”

The issue of COVID-19 spreading in the dormitories has presented the Singapore government with a headache of epic proportions.

Two days before Singaporeans began their “circuit breaker” — a partial lockdown period, lasting up to June 1, during which non-essential workplaces are closed, students undergo home-based learning, and gatherings of any size in any space are banned — the government announced the game plan.

Lawrence Wong, Minister for National Development and co-chair of the multi-ministry task force on COVID-19, laid it out at a press conference. The government was splitting locally transmitted cases into “two separate categories”: cases in dormitories, and everyone else. Workers would be largely confined to their lodgings, “so that there will be no infection to the rest of the community.”

“With the foreign worker dormitories, looking after the workers there, taking care of their welfare, looking after all their well-being but also taking all of these precautions, I think we would be able to ring-fence and contain the infected cases in the foreign worker dormitories,” the minister said, before moving on to talk about “cases within our own community, by residents in Singapore.”

Once again, as Fordyce has pointed out, migrant workers were being treated as “a whole different category”. The government’s daily update on the number of new COVID-19 cases also separates dormitory cases from community cases.

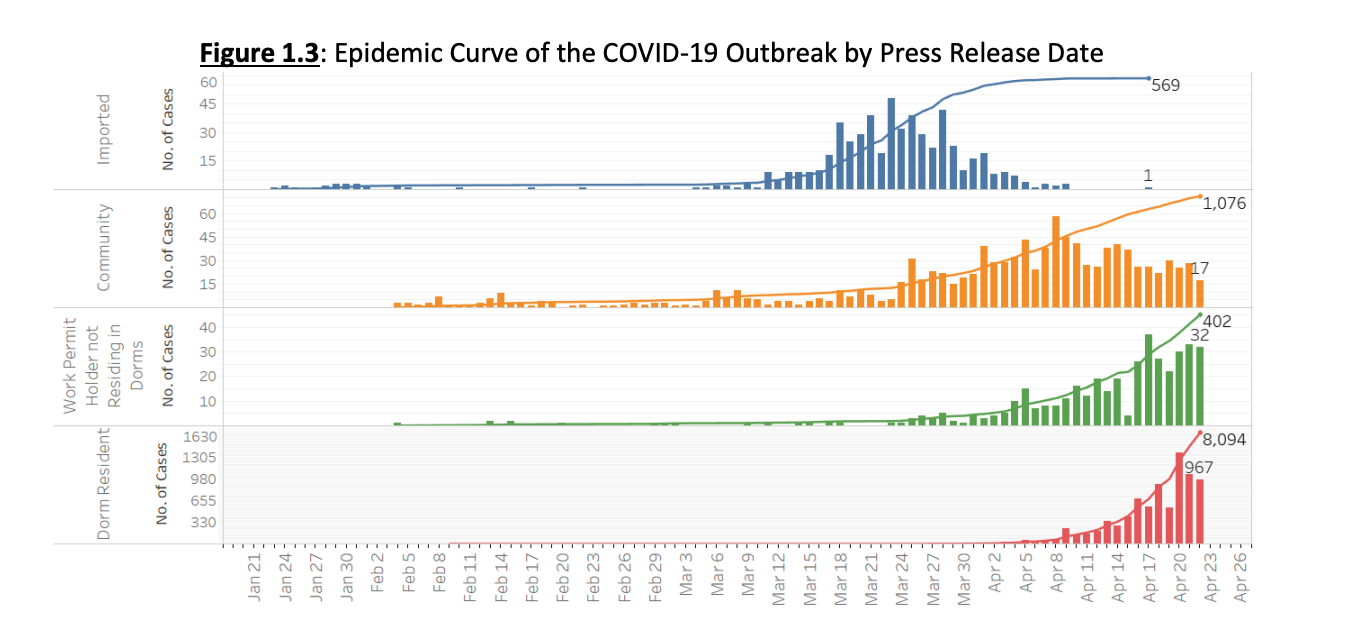

(A screencap from the April 22 situation report, with cases disaggregated into “Imported”, “Community”, “Work Permit Holder not Residing in Dorms”, and “Dorm Resident”.)

Dr Paul Tambyah, president of the Asia-Pacific Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infection, tells me that making such distinctions between dormitory and other community cases doesn’t make sense from a public health point of view, “as there is considerable overlap in the categories. The workers clean our offices, build our homes, repair our roads, etc. They also lay our high-speed internet cables in our homes and shop at some of the same stores that we do. There are many other reporting approaches used by the authorities for other conditions such as by age, or residential location, as we do for dengue.”

While the move to distinguish cases into “two separate categories” might have been motivated by practical or logistical concerns, it ends up Othering an already marginalised population, leaving them open to racist attacks and stereotypes.

A letter to the Chinese-language newspaper Lianhe Zaobao urged Singaporeans not to blame the government for the spread of COVID-19 within dormitories, instead pointing the finger at the “poor personal hygiene” of the workers, who the writer characterised as coming from “backward countries”.

Migrant workers are acutely aware of these prejudices. A Bangladeshi worker in a gazetted dormitory agrees to speak with me over the phone. But when asked if he would like his name to be included in this piece, he refuses.

“I think [there’s] no need to put my name,” he says. “[Some] Singaporeans don’t like foreign workers. [Most Singaporeans] are okay, but there are [some] who don’t like us.”

Confusion behind the (ring)fence

While this isn’t the first attempt to ring-fence COVID-19 — previous examples like the lockdown of Wuhan, or the quarantine of the Diamond Princess cruise ship, come to mind — the Singapore government is faced with a daunting task. With thousands of men confined to their rooms in now-quarantined dorms, there are immediate questions in need of urgent answers; issues of food, cleanliness, hygiene, access, and communication that all have to be dealt with right away.

While Ministry of Manpower press releases speak of dormitories where conditions have been “stabilised”, comments from the minister point to the pressure the civil service is under.

“The [Ministry of Manpower] team is fighting the battle on many fronts — job security, business viability, wage/leave issues, manpower surplus/excess in different areas, loss of income by self-employed, concerns from employers about domestic workers and vice versa — a long list,” wrote Josephine Teo, the manpower minister, in an April 11 Facebook post. “My team is stretched to the limit.”

The demands of rapidly locking down complexes housing thousands of people has led to confusion on the ground. Conditions vary from dormitory to dormitory; while some workers say that things are all right where they are, others have run into problems.

On April 10, a day after the gazetting of Sungei Tengah Lodge, TWC2 received a call from a worker with a hip injury. He was in need of paracetamol to manage his pain. He’d first asked the dormitory’s security officers for help, and had been told to pay S$150 for an ambulance to take him to hospital.

The NGO spent the rest of the day, and most of the next, trying to figure out if there was an on-site medical team, and if it would be possible for the worker to get what he needed. Finally, a TWC2 volunteer decided to bite the bullet and simply drive over to Sungei Tengah Lodge with two boxes of Panadol. I met him there.

That day, TWC2 was successful in handing over the medication; the man in charge at the gate was friendly and made sure that it reached the worker in need. But other workers have flagged a variety of issues, from the quality of food to cleanliness within the dormitory, and even a case of being literally locked inside their room.

“For the nation, for our migrant brothers”

On April 14, Zakir, the migrant poet, began to feel feverish. By that point, COVID-19 clusters had been identified in his dormitory, and the complex was already gazetted as an isolation area. “I was thinking that, in the dorm, there was no one checking temperature, so I went to [the] security [officers] and I told them that I would like to go to the hospital,” he tells me over the phone.

By the time he got to hospital, Zakir was feeling so ill that he could barely sit in the waiting area. Nurses had to help him into a bed. He was transferred to a ward the next day, where he shares a room with three other migrant workers, all from India. He was informed on April 17 that he’d tested positive for COVID-19.

When we speak in the evening of April 18, Zakir sounds a little more like his old self, barring a cough. He says he’d been unable to eat for the past couple of days, but had just had dinner. “I think this is the first time I eat all the rice, and the chicken and the vegetables, after I enter the hospital,” he says.

Zakir’s anxiety has shifted from his own situation to that of his peers. He’s been coordinating donations of essentials, such as face masks, hand sanitiser, and cleaning products, to various dormitories in need. He’s using the network he built with One Bag One Book, a migrant worker-driven initiative seeking to inculcate a love for reading among workers in Singapore. Zakir says there are One Bag One Book readers in most purpose-built dormitories in Singapore, and some, across 13 dormitories, have come forward to help with the distribution of essentials.

There have been previous successes at distributing items, but they’ve run into obstacles. Donors had tried to deliver masks and other necessities to a dormitory where workers had flagged a need. Unlike TWC2’s fortunate encounter, the donors were told that their items could not be distributed, even though One Bag One Book’s volunteers were already present within the dormitory. They were told that all donations now have to go through the Ministry of Manpower.

Driven by worry for the safety of his fellow migrant workers, Zakir’s still coordinating One Bag One Book’s activities from his hospital bed, communicating with donors and migrant worker volunteers. His wife back in Bangladesh can’t even call him properly, he says, because calls keep coming in from various dorms asking for supplies. He’s also found that donors are much more receptive and generous if they’re able to hand things over to workers directly, and worries that regulations blocking deliveries to dormitories will affect One Bag One Book’s efforts.

Migrant workers aren’t allowed to officially register organisations in Singapore; the rules don’t even allow them to be committee members of NGOs meant to represent their interests, such as TWC2 or the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME). One Bag One Book is, therefore, an informal entity.

Nevertheless, Zakir hopes that migrant workers will be allowed to play a greater role in the fight against the coronavirus. “We [want to] take part in this crisis for the nation, for our migrant brothers.”

Some coordination efforts are underway. On April 17, the Ministry of Manpower said that an inter-agency task force on COVID-19 in dormitories is collaborating with a number of organisations to provide for the workers’ well-being and distribute essentials.

“It is critical that these efforts are coordinated in an orderly way,” the ministry said in a statement. “Having dedicated vast amounts of public resources across the whole of government, we must not risk uncoordinated actions compromising the integrity of ground operations and weakening their effectiveness.”

At the centre of these operations is the Migrant Workers’ Centre — an initiative of the Singapore National Employers Federation (SNEF) and the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC), the national labour movement that’s closely intertwined with the ruling People’s Action Party — as well as smaller NGOs. Both TWC2 and HOME, two migrant labour rights organisations that have been outspoken about the need for structural and systemic change, weren’t mentioned in the press statement.

“You couldn’t stay here for 10 minutes”

It’s not enough to fence off the dormitories. Without safe distancing within, a lockdown would only leave the virus to sweep through the population, passing from one crowded room to another. As a matter of urgency, it’s imperative to spread the men out.

With thousands of men to move, all sorts of housing options have now been roped in, or are being considered. Military camps, vacant public housing blocks, floating lodgings, sports halls, hotels, car parks, and cruise ships are all part of the effort to relocate men.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Singapore’s utilitarian bent has come to the fore. Healthy men working in services deemed essential, such as cleaning housing estates or maintaining the country’s broadband networks, have been prioritised; according to Minister Josephine Teo on April 14, 7,000 have already been shifted to alternative accommodation. “Medical screening was conducted to ensure that the workers did not have symptoms before moving into the alternative accommodation,” the Ministry of Manpower said in a statement.

It’s not clear if all these men have been tested for the virus; while the ministry’s statement only mentioned screening for symptoms, Minister for Health Gan Kim Yong mentioned on April 21 that essential workers were being tested. While working on this story, I sent questions to the Ministry of Manpower — including questions about testing and the government’s plans for moving men out the dormitories — and followed up a couple of times, but haven’t yet received a response.

Dr Paul Tambyah, the infectious diseases expert, says prioritising these workers runs the risk of further issues down the line. “Separating ‘essential’ workers also has problems from a public health point of view, as some of them may be incubating the virus and thus they could spread the infection to those they are living and working with,” he says. (According to the small number of studies that have been carried out thus far, individuals who are incubating the virus could test negative until about a day or two before symptoms appear.)

“It makes more sense to use the strategy used in February, which was to quarantine all close contacts regardless of whether they were family or work contacts. Keeping them in single rooms reduced the risk of secondary or tertiary spread.”

In any case, Debbie Fordyce of TWC2 says that all this should have been prepared and executed much earlier. “The thinning out [of the dormitories] is happening very, very late, and confining people to dorms with large numbers of people is extremely dangerous,” she says. Now, with the men spending their days cooped up, “it’s almost as if the workers are locked into certain areas where they might all catch [the coronavirus].”

This reality is hitting the workers hard. The Bangladeshi worker who had asked to remain anonymous tells me that stress levels in his gazetted dormitory are rising. “We understand [that the] Singapore government is trying their best, but it’s very difficult. Our life [now], every moment is panic, every moment is danger. Every moment someone is crying... Even myself, my wife [in Bangladesh] — and I have one small baby — every time I’m talking to them, they’re crying, thinking too much.”

The poor conditions of the dormitory are also sinking in like never before. As the worker points out, they’ve never spent so much time in their rooms before. Previously, these bunk beds had only been somewhere to grab a few hours of sleep before another day of work. Now, their days are confined within the limits of the cramped room.

“I can say to you, [Singaporeans] cannot stay in my room for five to 10 minutes. You cannot, you all are used to aircon and everything. You can’t stay here for 10 minutes,” he says.

There are 12 men, with their accompanying luggage and belongings, living in a room the worker estimates to be about six metres by eight metres. There isn’t even a metre between the beds, he says. There’s only one door, and two windows on one side of the room. There are two ceiling fans. The heat is unbearable; one is soaked in sweat even from a half-hour nap.

Outside the room, the worker says that eight to 12 toilets, shower cubicles, and basins are shared by over 100 men. Cleanliness is difficult to maintain at that level of heavy use. Other facilities are also being shared. “We all wash our [clothes] and dry them at the same place,” the worker says.

“I don’t know if [the room closest to mine] has the virus or what, I put [the clothes in the] same place, my friend also puts [his in the] same place, everybody’s [in the] same place.”

These are all issues that need to be tackled right away, but the system is already strained under the weight of all that needs to be done. As former diplomat Bilahari Kausikan put it in a Facebook post, Singapore “did drop the ball” when it came to migrant workers and the coronavirus outbreak; the famously efficient country simply wasn’t prepared for this.

It’s led to suboptimal moves: instead of seeing a reduction in density within their room, this worker has seen the number of men in his room increase from nine to 12. When the men asked the dormitory management why they were getting new roommates in the middle of a lockdown, they were told that rooms were being emptied out to be converted into isolation or quarantine areas, so their occupants had to be shifted to other rooms with spare bunks. (This seems to be in line with what Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in his address on April 21, when he said some workers with mild symptoms of COVID-19 will be housed in separate facilities within dormitories, while others will be moved to community care facilities.)

The management assured the bewildered workers that the newcomers would only be there for two weeks, but it isn’t clear what’s going to happen next. None of the men in that room have been tested for COVID-19.

Fordyce is bracing for things to get worse, not only because the number of infected workers continues to rise, but also because other issues are going to come into play soon enough. “Right now we haven’t quite seen all the shit hit the fan yet,” she warns.

“Right now the fear is still about whether they’re going to catch the virus and how to keep safe from it,” she continues. “In the longer term, it’s going to be about whether they are going to get money out of this time they aren’t working, and what will happen to their jobs.”

Almost S$675 million will be paid out to employers as part of a first tranche of foreign worker levy rebates, to help bosses care for the upkeep of their workers during the lockdown. Although the government has stated that workers in dormitories should continue to be paid while under quarantine, NGOs say more needs to be done to make sure this happens. Even before the coronavirus, wage theft and debt bondage were common problems handled by NGO case workers. At a time of crisis and economic slowdown, employers might be looking to tighten their belts further.

“HOME has already seen numerous cases of workers who have been laid off overnight and consequently lost access to their accommodation and food,” wrote the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics in a statement.

The challenge with tests

In the early days of the outbreak, Singapore was getting kudos for testing and tracing. But the numbers are now stacked against the system.

From the beginning of the outbreak in January until April 14, the country tested 94,796 swabs, from 59,737 unique persons. But with over 320,000 migrant workers stuck in dormitories and at risk of having (or getting) COVID-19, testing this population would require Singapore to carry out more tests than it’s ever done.

“In effect, we would have to screen each and every one of them… We may have to do an entry as well as an exit [test], which means 200,000 [the number of men in the 43 purpose-built dormitories] times two, 400,000 [tests],” Dr Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious diseases physician, told the Straits Times during their weekday talk show The Big Story.

“That’s a major tall order, huge amount of resources implemented. And mind you, we’re a small country which is fighting for all these reagents among the big players, including Germany, USA, and Korea. Will... our requests for reagents get fulfilled? That’s another issue.”

The government says they are “aggressively” testing migrant workers. On April 21, Kenneth Mak, the director of medical services at the Ministry of Health, said that the country is doing up to 3,000 tests per day, of which 1,500–2,500 are being carried out on migrant workers. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has also assured the nation that Singapore is working on both procuring more test kits from abroad, and developing its own.

That said, even up to 2,500 tests a day likely still isn’t enough when there are 323,000 workers living in dormitories, and every reason to expect COVID-19 to still be spreading within those complexes.

To speed up the process, TWC2 has suggested pooled testing, where samples are taken from multiple people and put together for testing. But Dr Paul Tambyah isn’t sure that it will work here: “Pooled testing is done in blood banks where 10 patients are sampled at one time in batches, so if one batch is positive for Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C or HIV for example, then that batch is broken up and the 10 samples are tested separately. That works for a rare condition… The number of people infected here is just too high.”

“One other approach would be to assume that everyone is exposed and/or infected and just try to isolate everyone, and then slowly test them as the labs are capable of doing the testing,” he continues. Those who are not well can then be sent to hospitals, clinics, or community isolation facilities as needed. He also adds that the Ministry of Health is “exploring multiple different platforms, and hopefully in the next few days will have some high throughput systems in place.”

Zakir is recovering in hospital. He says that another roommate had tested positive for COVID-19 before him and is also hospitalised, but his other roommates haven’t been tested. He’s also heard that there are still cleanliness issues in the shared toilets and bathrooms at the dormitory.

“This is actually… ignoring migrant health from the dormitory [management] side,” he says. “If they aren’t ignoring [this], they have to clean the toilet area. The toilet area is so dirty, people cannot enter, [it’s] very dirty, but they [didn’t] clean.”

Communication is also an issue. Men aren’t always told the result of their colleague or roommate’s test — or sometimes even their own. “Some people are tested and then they’re moved someplace else and they themselves don’t know the result of the test,” Fordyce says. “They don’t know if they’re being moved and they’re going in with healthy people, or because they’re sick and they’re going in with sick people.”

The worker who asked to be anonymous is hoping that he and his peers can be tested soon. “I don’t know when they will test us, maybe it’s better for us to test. Once we test, I can understand [that] I am virus-free, or I’ve got [the] virus. Now it’s [just] panic.”

Learning from this outbreak

It’s going to be some time until Singapore’s struggle against COVID-19 is over. The country’s “circuit breaker” partial lockdown has been extended from May 4 to June 1, after which the government will assess the situation before making a decision about whether to lift it.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has said that “almost all” infected workers identified so far have only had mild symptoms. “We hope that the situation in the dorms will remain this way: most of the cases being mild, and very few needing oxygen or intensive care,” he said in his address to the nation on April 21.

But the possibility that some will develop more serious symptoms remains. Some of the Bangladeshi workers who’d been among the early infected cases were observed to have spent a relatively long period in hospital. The very first worker who tested positive spent over two months in intensive care before being transferred to a general ward on April 16, where he will require further rehabilitation like speech therapy.

No matter how the situation develops, shock at the scale of the problem in dormitories has prompted calls to improve conditions. Parliamentarians have called for the raising of living standards for workers, while analysts predict a tightening in regulations for dormitory operators.

Fordyce thinks it’s important for everyone to remember that it isn’t just an isolated issue. “Now everyone is focused on the dorms, and it’s once again as if all the other things that migrant workers are meant to put up with are getting ignored,” she says.

“It’s always been the case that migrant workers were expected to exist under very different conditions. It’s not only the workplace, it’s the job as well. And it’s also the amount of remuneration that they’re getting.”

COVID-19 has spurred an unprecedented amount of public awareness and momentum for advocates of migrant labour rights. More action is going to be needed once the worst is over; Josephine Teo, the manpower minister, has promised as much. Until then, the anonymous worker says there’s little else to do but hope for the best.

“We’re all praying to overcome this situation,” he says. “I hope my Singaporean friends are also praying for us.”

If you would like to donate to organisations supporting migrant workers at this time, you can donate to Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) or Healthserve, or to the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME).

Thank you so much for reading this piece! I’d really appreciate it if you could share it with your friends and family (and anyone else, really). If you have any questions, feel free to ask them in the comments — I’ll try to answer as much as I can without compromising the safety of sources.