WTC Long Read: A mother’s concerns in a time of POFMA

The following piece is one that I’m publishing only after a lot of thought and consideration, more than any other piece I’ve done. I’ve ultimately decided to publish it because I feel like the issues raised, particularly those related to accountability, independent oversight, and the climate in Singapore for truth-seeking, are important to public discourse..

Except where indicated, I’ve used people’s given names.

Normalah has been worried about her son, Sallehin, for a long time. He’s a “lifer” — sentenced to life imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane in 2017, after he was convicted of importing not less than 378.92 grams of methamphetamine.

But it isn’t just Sallehin’s imprisonment that’s worrying his mother; she’s more anxious about how her son is being treated within the confines of Singapore’s Changi Prison.

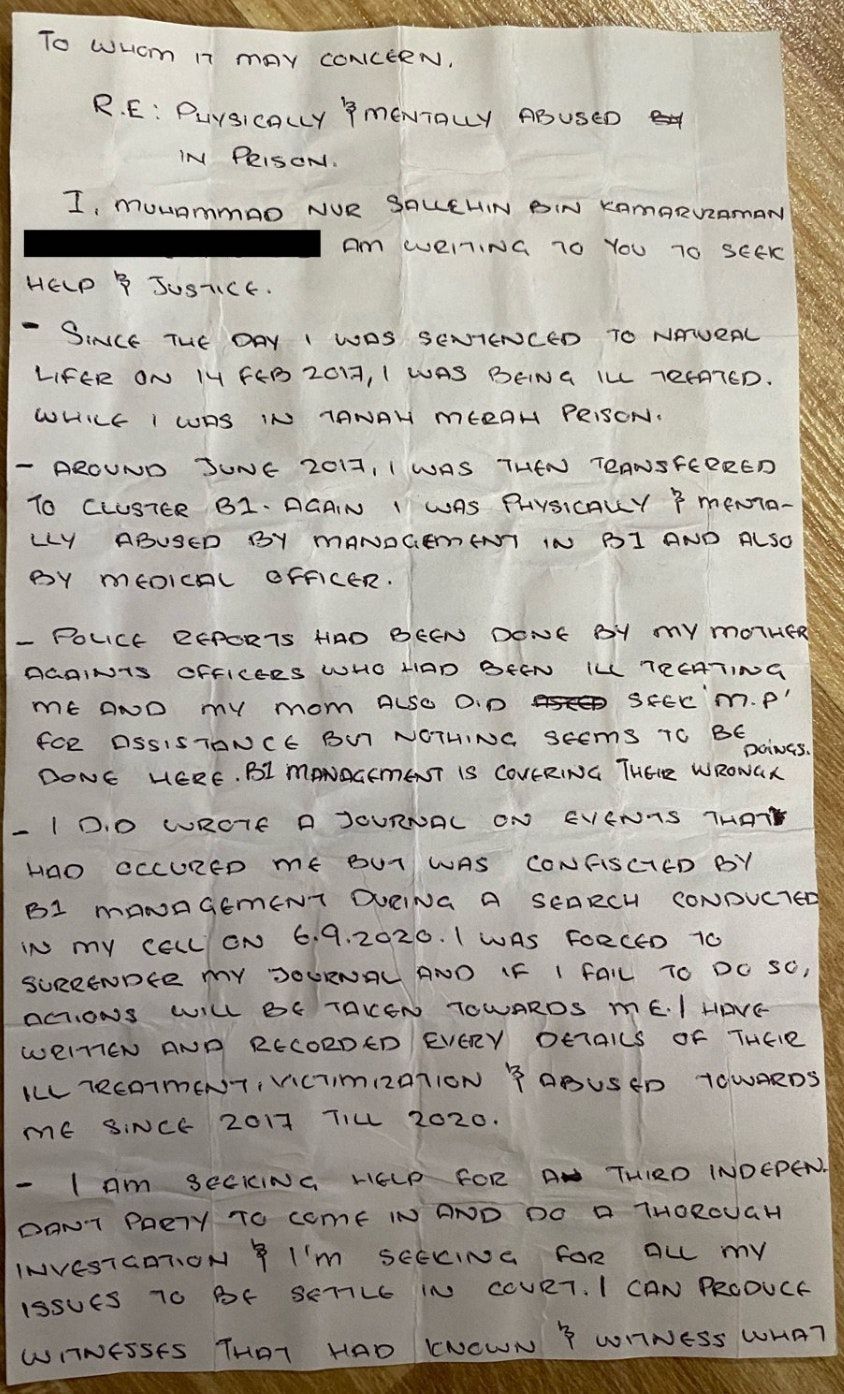

It was 2018 when she first told me of her fears. She showed me accounts that Sallehin had written; she’d meticulously kept them all in a file. In small, curved capital letters, Sallehin wrote about his treatment behind bars and his troubles with various prison officers.

Sallehin’s allegations

In these written accounts, Sallehin claimed that his dietary needs had been ignored by the prison. According to Sallehin, in December 2017, after days without food (he wrote that he couldn’t eat the meals given), he was brought to the prison clinic and sent to the psychiatric ward, where his hands and legs were cuffed to the bed.

“I asked the prison staff why am I being treated this way and what they told me was because I have not been eating for four days and this is all doctors instruction we can’t do anything to help you,” he wrote.

In his account, Sallehin wrote that both the leg cuffs and one hand cuff were eventually removed, but that he was still kept cuffed to the bed even when it was time to bathe. His blood sugar kept dropping, and he was eventually taken to Changi General Hospital after blacking out.

After being discharged from the hospital, Sallehin wrote that he was again put in an isolation ward in the prison and cuffed to the bed. He then alleges that, when he was returned to his cell, the prison doctor did not see him even after he reported sick.

In another written account, Sallehin claimed that he was assaulted by a prison officer in January 2018 after he’d taken issue with the food that he’d been given. He wrote that the officer had roughly pulled his arms behind his back, ignoring an injury in his left arm that made it painful to move, and that he’d been pushed to the ground and stepped on, including near his groin.

“My injury from this whole incident are left elbow abrasion, left knee abrasion, bump on my right forehead, both my shoulder spraint, left knee sprain and a swollen right wrist,” he wrote.

He was then sent to the detention housing unit. He wrote that when he asked prison officers to photograph his injuries, they told him there was no need to do so. Again, Sallehin alleged that he did not receive medical attention in prison even after reporting sick. On 16 January 2018, he wrote, he was warded in Changi General Hospital, where he remained until early February, for high blood pressure and low blood sugar.

In a note written in 2020, Sallehin reiterated claims of ill treatment. He also alleged that the prison had confiscated his journal, in which he had recorded instances of abuse.

Normalah’s efforts

Alarmed by what she’d heard from her son, Normalah took action. From 2018 up to this year, she tried various ways to get the matter addressed: she contacted the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), filed police reports, and went to see Members of Parliament. She also showed me letters, written by lawyers who were then acting for Sallehin, sent to the Attorney-General’s Chambers and the prison to lodge official complaints in 2018. An October 2020 letter from the prison highlighted that she’d written to them 14 times over the past two years.

“All avenues I tried, but I was disappointed,” Normalah tells me in an interview with the help of an interpreter. She speaks some English, but prefers to speak in Malay. “But whatever happens, I will still continue my effort.”

The authorities have denied all of Sallehin’s allegations. In a letter dated 16 March 2018, a quality service manager from MHA wrote:

“The Ministry of Home Affairs does not condone any mistreatment of inmates and assure you that the safe and secure custody of inmates is our paramount concern. Our investigations indicate that Sallehin has not been abused or mistreated in the incidents that you have raised. Sallehin has committed 12 disciplinary offences in prison to date. Even while he was segregated for investigation into his disciplinary offences, the SPS has ensured that there was adequate food and water for him, and he is accorded necessary medical attention when he reported his ailments to the medical service providers.”

The Singapore Prison Service reiterated this denial on 16 August 2018, adding that:

“Sallehin was not denied medical attention. He has repeatedly refused to consume his hypertension medication prescribed by CGH and we have accorded appropriate medical attention to him and advised him repeatedly to comply with his prescribed medicines. Our Prison Medical Officer has also informed the CGH Specialist that your son has refused to consume his hypertension medicine and we have since stopped this medication for him. In addition, Sallehin did not report to staff that he had a swelling on his head on 19 July 2018 and there was also no record of him reporting sick in the month of July 2018. It was in January 2018 that Sallehin had repeatedly hit his own head against the wall.”

Normalah hasn’t found any of this to be reassuring. Although she’d met with prison officers face-to-face, she says her request to meet the prison officers with Sallehin also in attendance, so she can listen to both sides at the same time, was rejected.

“I told them, ‘if my son is not there, the experience is not mine, how can I answer you properly?’” she says. “If my son was there, then he can explain what he has undergone. Obviously when it’s just me alone then the officers would only tell me one side of the story. If face-to-face with the officers and my son, then I can get the two sides’ perspective, I might be satisfied.”

In one letter dated 21 March 2019, the prison claimed that Normalah had given up on her request to meet with both the officers and her son at the same time. They said she had “agreed that the request to meet up with officers, Sallehin and other family members may be futile if Sallehin continues to have differing views from officers on what had happened in prison.”

Normalah insists to me that she’d never agreed to any such thing. Although prison officers have suggested to her that Sallehin is lying, she tells me that she believes her son and is worried for his safety and welfare.

After Sallehin’s time at Changi General Hospital, she’d asked for his medical documents, but was rejected. “I wanted the medical certificates direct from the hospital, they wouldn’t let me,” she says, adding that she was told the prison would have to give permission for her to see her son’s medical records.

An email sent to Normalah by a prison staff officer in April 2019 stated that she could obtain a medical report on her son from the Prison Medical Officer. She would first have to pay $240.75, and the report would be ready two to six weeks after payment. But Normalah says that’s not what she wants.

She appears to have lost faith in the prison system. “I asked them for the medical documents direct from the hospital, this was not given,” she says. “If I get medical documents that come from the prison authorities, they can fabricate stories… I need to get it direct from the hospital, not mediated by the prison authorities.”

In a letter dated 7 October 2020, after Normalah filed a police report and met PAP MP Mariam Jaafar, the Singapore Prison Service addressed Sallehin’s claims about his confiscated journal: “The officers had confiscated the stack of papers from Sallehin during a scheduled search, as they were used inappropriately and without authorisation.”

In a letter dated 28 October 2020, after Normalah made further appeals to Mariam Jaafar for help, the Singapore Prison Service again reiterated that Sallehin’s allegations were “not substantiated”.

“Please be informed that the Singapore Prison Service (SPS) takes a serious view towards any groundless accusations made by inmates, and hence, Sallehin will be liable to answer to this disciplinary offence,” the letter said.

Normalah says this response still doesn’t address her worries. “I’m not satisfied, I will do it [lodge complaints] again!” she tells me. “There’s no answer… my son kena beating, [and the prison says] ‘Oh everything settle, check already, clear already!’ After that, they close the case. But I’m not happy.”

A journalist’s headache

Listening to Normalah, watching her splay the documents out before me, a dilemma grew in my mind. How should I do this story?

There isn’t much transparency into how Singapore’s prisons are run and what happens behind those walls. Yet the prison service is an organ of the state, and people are incarcerated in places like Changi Prison and Tanah Merah Prison in the name of keeping Singapore and Singaporeans safe. If the rights of prisoners aren’t being respected, or if there is mistreatment or maltreatment going on, it’s a matter of public interest. If, as Sallehin is alleging, prisoners have problems getting adequate medical attention and treatment, and are being bullied or even assaulted by prison officers, people should know about it.

The “ownself check ownself” system of internal investigations is also problematic. Singapore doesn’t have an ombudsman to whom citizens can lodge complaints against public institutions, nor does it have any other independent mechanism that will scrutinise organs of the state and other public agencies. When Normalah filed police reports about her son’s allegations against the prison, she was informed by the police that her appeal had been “referred to the Singapore Prison Service for their consideration”.

There is the Board of Visiting Justices, appointed by the Minister of Home Affairs, that’s meant to inspect the prisons and make sure that prisoners are being taken care of. Under the Prison Regulations, Visiting Justices should “hear any complaint which any prisoner may wish to make to them, and shall especially enquire into the condition of those prisoners who are undergoing solitary confinement.”

In their written communication, the Singapore Prison Service informed Normalah that the Board of Visiting Justices had seen Sallehin in September 2018, but that “[the Board of Visiting Justices] understood and did not raise any further queries after we explained to them that the allegations raised by Sallehin were baseless.” From this, it doesn’t sound as if the VJs conducted an independent inquiry into Sallehin’s claims themselves.

Media access to prisons is also limited, particularly to freelance journalists like myself; anyone who visits a prisoner like Sallehin will have to first apply with the prison authorities and seek their approval.

In January 2019, a British journalist from the Daily Mail was banned from any further visits to the British inmate Yuen Ye Ming, after conducting an “unauthorised interview” with Yuen about his experience in prison. Yuen’s family had registered the journalist for a tele-visit, saying that he was a family friend.

“SPS does not allow interviews to be conducted with prison inmates without prior approval,” the Singapore Prison Service told Channel NewsAsia.

This is not to say that the prison service definitely lies or engages in cover-ups. But it isn’t unreasonable or ridiculous for people to point out the conflicts of interest inherent in allowing an institution to investigate itself. This leads to “he said, she said” impasses like the one between Normalah and the authorities right now, with no independent third party able to carry out a thorough investigation.

I can’t verify Normalah or Sallehin’s claims. Nor can I verify the statements made by the authorities. So how can I tell this story, without being accused of spreading “fake news”?

The POFMA problem

In 2018, the government talked about tackling the scourge of “fake news”. The Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, or POFMA, came into effect in October 2019. The law gives government ministers the power to issue orders to “correct” false statements of fact on the Internet, demand that they be taken down, or insist that social media platforms block Singaporeans’ access to that content.

POFMA also lays out criminal penalties for those who communicate statements that they know, or have reason to believe, are false, and that might be against the public interest, such as diminishing public confidence in an organ of the state. If convicted of such an offence, the penalty for an individual is a fine of up to $50,000, imprisonment of up to five years, or both.

While still committed to writing about human rights issues, I’m not keen to walk straight into getting POFMA-ed, or charged for deliberately spreading falsehoods. This uncertainty and concern led me to drag my heels on this story for much longer than I would otherwise have had. I met Normalah over and over again over the years, talking about her son’s situation in prison multiple times. Each time, she was consistent and persistent in speaking up for her son.

Previous deaths in custody

On more than one occasion, Normalah mentioned the case of 21-year-old Dinesh Raman Chinnaiah, who died in prison in 2010 following a scuffle with eight prison officers. The state accepted responsibility for Dinesh’s death, and a deputy superintendent pleaded guilty to one charge of causing Dinesh’s death by negligence not amounting to culpable homicide. However, the internal disciplinary proceedings of the other officers involved were not disclosed. As activists noted at the time, the Ministry of Home Affairs also did not make the findings of its Committee of Inquiry audit into prison systems public, and the State Coroner discontinued his own inquiry, saying that the criminal proceedings had made it redundant.

In a public statement, the Ministry dismissed some of the allegations made by Dinesh’s family against the prison as “false” and casting “aspersions on the integrity of the prison service, police investigations and the criminal justice system”. They described the compensation quantum used to compensate the family for the loss of Dinesh as a “generous approach”, and said that the family had been “prepared to ‘settle’ the matter for substantial windfall amounts”.

In 2011, Lian Huizuan died in Changi Prison from overmedication of drugs prescribed to her while in custody. A post-mortem found that the blood level for a drug in her system was 19 times higher than the expected therapeutic range. The prison psychiatrist told the coroner’s court that he’d had to see too many patients within a limited amount of time. He also said that he hadn’t been aware of other aspects of her medical condition — such as the severity of Hepatitis C — or multiple reported cases of falls and fits documented in her Inmate Medical Records. Other lapses, such as nurses failing to follow prison requirements to record dispensation of medication into the prescription chart, were also identified.

Her father told The Online Citizen that he and his daughter had both made multiple complaints or reports about her condition to the prison officers, but felt that no one had paid any heed.

Cases like Dinesh’s haunt Normalah. “What if something like that happens to Sallehin?” she asks. “Then it will be too late.”

“This case I will bring forward no matter what,” Normalah insists. “It’s not just my son who I am trying to defend, but also the [other] inmates inside the prison.”

What other former inmates say

With Normalah’s help, I met other former inmates, people who’d known Sallehin and spent time in the same part of the prison he’s currently in (other clusters or blocks within the prison system might be run differently).

Over a period of months, I spoke to six ex-prisoners about their experience behind bars. I met them to further understand conditions inside Singapore’s prisons, and to see if I could corroborate the things I’d read in Sallehin’s letters and the documents that his mother had collated. I’ve replaced their names with initials to protect their privacy.

For the most part, the former inmates I spoke to were interviewed separately. There were things they said that were consistent from interview to interview; some even independently brought up the same anecdotes.

All interviewees said that Sallehin isn’t well-liked among prison officers, some of whom would make life difficult for him, finding reasons to punish him for real or perceived infractions, leading to the denial of privileges or time in punishment cells. None of them had witnessed Sallehin being beaten — one, though, said he saw bruises on Sallehin when they were being transported together to attend hospital appointments — but some had their own allegations of physical assault.

“Sallehin like to complain… so they don't like Sallehin. They don't like people, they hentam [beat] lah. Sometimes they never hentam, they use other ways, they do in a soft way, like never give us work, our request all reject,” said B, who spoke to me after spending over a year behind bars.

B said that Sallehin had told him about what he’d experienced when they met during yard time. “But when we ask officer, officer of course say no lah, correct? Say Sallehin lie lah, Sallehin wayang [pretending] lah, like that lah,” he added. “But I know this thing happen, because this thing ever happen to me, so I don't think they lie. I don't think Sallehin lie.”

As for himself, B said he was never beaten in Changi Prison, but had been assaulted while in Tanah Merah Prison: “We all also kena hentam, only for that place. They can hentam people anyhow, you know, I tell you… Hentam like nobody business, like no law like that.”

Z is another interviewee who claimed that he’d been assaulted at Tanah Merah Prison. Speaking in Malay through an interpreter, he said that prison officers had kicked and hit him while telling him, “If you’re a gangster let us show how powerful we are, you’re under our feet.”

W, who served time for robbery, explained that there were barriers to lodging complaints with the Visiting Justices. “Even when the Visiting Justice come, we can't complain,” he said, claiming that some inmates were worried about the repercussions of complaining to these external visitors. The asymmetry of power means that it can be easy for officers to come up with infractions to penalise inmates for, or to target particular inmates with extra spot-checks and scrutiny.

Reaching out to the authorities

Earlier this year, Normalah decided that she wanted me to meet Sallehin in person. She applied on my behalf to the prison, listing me as a friend. Permission was at first granted — I received a text message on 28 September 2020 informing me that the request had been approved — but Normalah was later told that it had been cancelled.

On 2 November 2020, I wrote to the Singapore Prison Service with a collated list of questions and a formal request to interview Sallehin. I wanted to get more information about the way the prison service deals with allegations of ill treatment, how investigations are conducted, how much external oversight Visiting Justices provide, and how the prison has dealt with other complaints it might have received.

These are the questions I sent, with slight edits to remove personal details like ID and prison numbers:

Firstly, I would like to make a request for an interview with [Sallehin].

Sallehin and his mother have made allegations about bullying and maltreatment, including physical assault, while he’s been in the prison’s custody. I understand from letters that the Singapore Prison Service wrote to his mother that an investigation was conducted and that his allegations were found to be baseless. How was this investigation conducted?

When a complaint of mistreatment or abuse is lodged, what is the prison’s standard process of investigation into such claims?

What power does the Board of Visiting Justices have to investigate complaints? Are they able to independently investigate allegations of abuse or mistreatment?

Some former inmates I have spoken to say that they were cautious of speaking to the Visiting Justices for fear of repercussions after making complaints. What is the Singapore Prison Service’s response to this? How does the Singapore Prison Service facilitate meetings with Visiting Justices?

I have also interviewed other former inmates who have alleged physical assault and unfair treatment in prison, such as punishments for perceived infractions if prison officers take a dislike to that particular inmate. Some have also said that it can be difficult to seek medical attention. I have a number of questions:

When there are such allegations, what avenues do prisoners have to lodge such complaints while in custody?

Has the Singapore Prison Service received such complaints before? If so, how often does the Singapore Prison Service receive such complaints?

How does the Singapore Prison Service deal with such complaints when it receives them?

Have there been instances where such complaints were found to be justified? What action did the Singapore Prison Service take then?

Have there been members of staff within the Singapore Prison Service disciplined or investigated in relation to complaints of assault or other forms of mistreatment?

Has the Ministry of Home Affairs or the Singapore Prison Service considered setting up external and independent oversight mechanisms to deal with complaints and allegations?

Truth-seeking in the POFMA era

I received a response from the Singapore Prison Service on 7 November 2020. This is the entirety of the statement:

International advocates and experts highlight the importance of external, independent monitoring. Many countries, like Northern Ireland and New Zealand, have external and independent oversight mechanisms like an ombudsman to address the sort of situation that Normalah is in now. But this isn’t the case in Singapore.

The lack of transparency and independent oversight, as well as the threat of laws like POFMA, are obstacles to truth-seeking in Singapore. It places journalists like myself, as well as activists and researchers, in the sort of dilemma I have described in this piece. It leaves people like Normalah and her son anxious and disillusioned, while institutions like the prison service have to deal with repeated reports and appeals from dissatisfied complainants.

Ultimately, I can’t conclude that Normalah, Sallehin, and the former inmates have lied, and I can’t conclude that they didn’t. I also don’t have any further insight into how the prison reviews and investigates complaints, nor can I independently verify the prison’s statements.

But I also can’t ignore this story, because it raises serious questions that are in the public interest.

If you would like to share this article, feel free:

If you’d like to become a Milo Peng Funder of this newsletter, just click the button below: