On 20 November, the Court of Three Judges suspended lawyer Lee Suet Fern for 15 months after finding her guilty of misconduct unbefitting an advocate and solicitor. This case has attracted public attention because it isn’t just any regular disciplinary complaint against a lawyer, but one that ties into the ongoing feud among Lee Kuan Yew’s children.

In this special issue of We, The Citizens, I’m taking a look at what the Court of Three Judges said in their 90+ page judgment.

At this point, anyone who’s been following Singaporean news, politics, and current affairs must know about the Lee family feud. If you need a refresher, you can refer to this GIF-laden round-up I did approximately a million years ago (or feels like it, anyway), in January 2019.

A quick sum-up: while the family feud also includes wider allegations of abuses of power, and has now entered the national political landscape with Lee Hsien Yang’s joining of the opposition Progress Singapore Party, a key trigger has been related to the family home at 38 Oxley Road. The younger Lee siblings, Lee Hsien Yang and Lee Wei Ling, are accusing their older brother, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, of wanting to preserve the house — and thereby go against their parents’ wishes for it to be demolished whenever Lee Wei Ling stops living in it — for his own political gain.

The younger Lees also took issue with a ministerial committee that had been convened to consider the matter. Lee Hsien Loong made statutory declarations submitted to the committee in which he expressed concerns about how Lee Kuan Yew’s final will had been made. He stated that although his father had had a “demolition clause” containing his wishes for the house in his First Will, that clause had been subsequently removed in later wills, but then “somehow found its way back into the Last Will.”

With this dispute, the confusing saga of Lee Kuan Yew’s many wills (and all the accompanying allegations/counter-allegations between the siblings) burst into public view.

In July 2017, Lee Hsien Loong and Teo Chee Hean made ministerial statements denying the siblings’ allegations of abuse of power and other naughty things (here’s my summary from back then). Following those parliamentary sessions, the siblings agreed to take the fight offline, although over the years we’ve seen occasional social media posts or public comments ranging from direct criticism to strategic breakfasting.

How does Lee Suet Fern come into this?

In January 2019, well over a year after the disagreement over LKY’s views and Lee Hsien Loong’s ministerial statement, the Attorney-General’s Chambers lodged a complaint to the Law Society against Lee Hsien Yang’s wife, the corporate lawyer Lee Suet Fern, for “possible professional misconduct”. The AGC said in a statement that Lee Suet Fern appeared to have prepared Lee Kuan Yew’s last will, triggering conflict of interest issues since her husband was a beneficiary.

NOTE: Although the AGC said that the Attorney-General had recused himself from the case, it’s worth noting that the current Attorney-General is Lucien Wong, who was previously Lee Hsien Loong’s personal lawyer. I’ll come back to this later.

What did the Disciplinary Tribunal say?

In February this year, a disciplinary tribunal found Lee Suet Fern guilty of grossly improper professional conduct and that disciplinary action should be taken against her.

The disciplinary tribunal found that there had been an implied retainer between Lee Suet Fern and Lee Kuan Yew, that she had acted as his lawyer in the matter of his Last Will, and that there was a clear conflict of interest in the matter. They said that her actions amounted to “grossly improper conduct” and that she “deliberately failed to discharge the duties that she was supposed to perform”. They even went as far as calling Lee Suet Fern a “deceitful witness”.

The Law Society then filed an originating summons to get the court to decide what disciplinary action to take; they were looking for her to be struck off, which would put an end to Lee Suet Fern practising law in Singapore.

So what’s all this with the wills, then?

One thing that’s been quite confusing to follow has been all the back-and-forth about Lee Kuan Yew’s many wills. The Court of Three Judges’ grounds of decision lays it all out — I have the full judgment, but only found a link to a case summary that’s publicly accessible online. I’m going to try my best to make it as simple as possible:

Between August 2011 and November 2012, LKY executed six wills, all of them prepared by Kwa Kim Li from the firm Lee & Lee. Each will superseded the one that came before.

There’s no need to know the differences between each and every will; all you need to know is that the First Will (dated 20 August 2011) gave each of LKY’s three children an equal share of his estate, and also included the “demolition clause” expressing his wish for 38 Oxley Road to be knocked down after Lee Wei Ling moved out. By the time it’d got to the Sixth Will (dated 2 November 2012), though, LKY’s instructions were to leave Lee Wei Ling a slightly larger share than her brothers, and the demolition clause had vanished.

In November 2013, LKY began talking about making changes to his will again. He discussed the matter with Kwa, his lawyer. An email that Kwa wrote to him on 13 December shows that he was thinking of going back to giving his kids equal shares. At the time, the discussion revolved around preparing a codicil to the Sixth Will, instead of replacing it entirely. There was some mention of the the possibility of the house being “de-gazetted” (which seems to indicate that LKY thought the house was gazetted? 🤔), but no mention of reinstating the demolition clause.

By 16 December, it seemed as if things had changed, and Lee wanted to revert to his First Will. So the idea was that he would re-execute the text of the First Will, making it his Last Will, which would supersede the Sixth Will.

That evening, Lee Suet Fern sent an email to LKY, Kwa, and Lee Hsien Yang. Attached to the email was a draft document that she said was “the original agreed Will which ensures that all 3 children receive equal shares”. She asked Kwa to engross the enclosed draft. For some reason, Kwa didn’t receive this email.

Shortly after that, Lee Hsien Yang emailed to say that he couldn’t get in touch with Kwa, who he’d removed from the email thread. He figured that she was away and it wouldn’t be “wise to wait till she is back”. He suggested that his wife get one of her partners at the law firm to get an engrossed copy of the will ready for LKY to execute. So Lee Suet Fern organised for a colleague to do that, and put that colleague in touch with LKY’s personal secretary. A little more than an hour after, LKY replied to the emails, agreeing to proceed with the execution of what would become his Last Will, without waiting for Kwa. On 17 December 2013, LKY executed the Last Will in the presence of Lee Suet Fern’s colleagues.

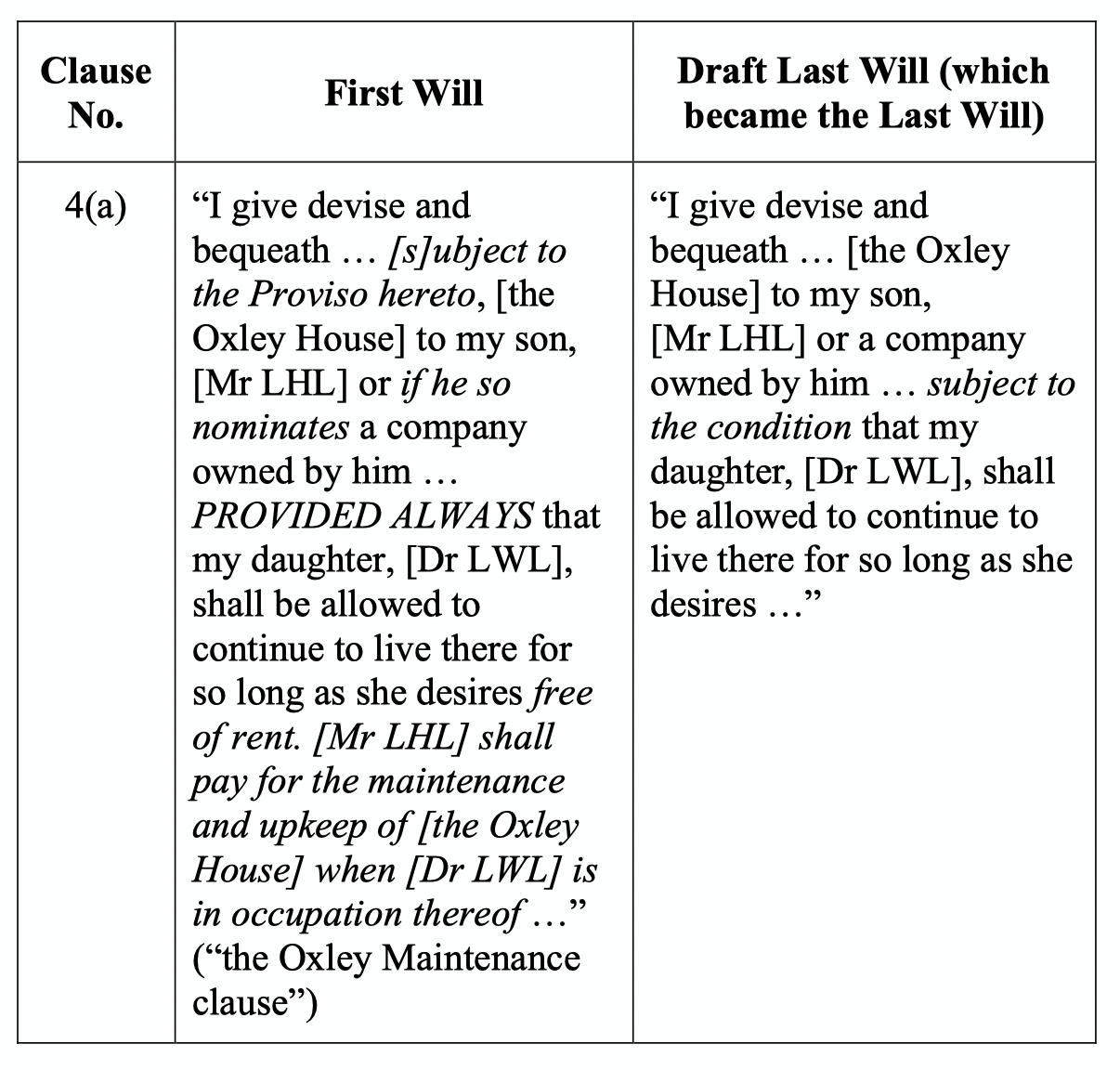

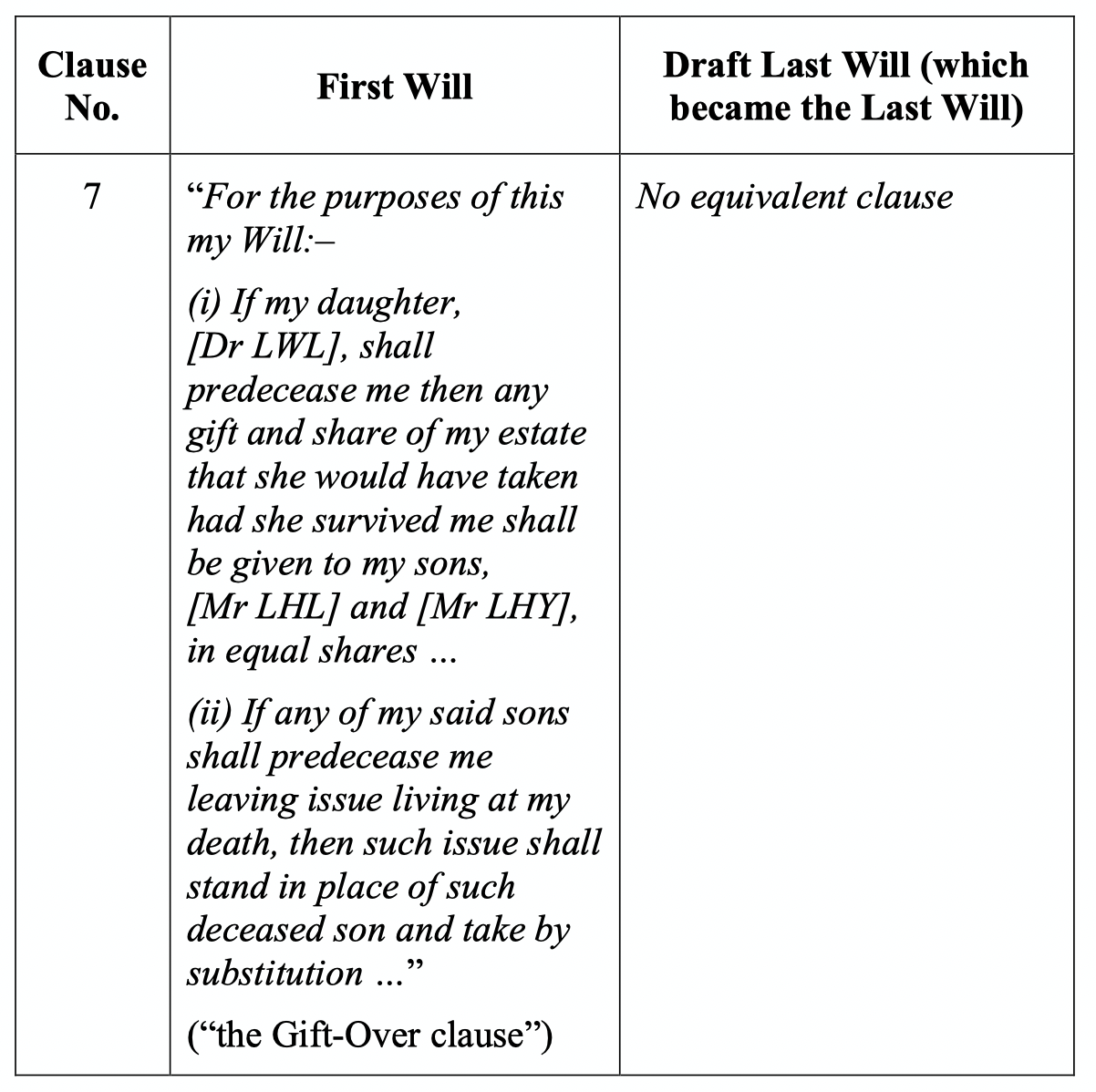

Now, the problem that crops up here is that LKY had wanted to go back to his First Will. But the draft that Lee Suet Fern had emailed was not actually the final text of the First Will — there were slight differences, laid out in the judgment:

The main differences seem to be that the Last Will, unlike the First Will, doesn’t specify that Lee Hsien Loong has to be the one to pay for the maintenance of the Oxley Road house while his sister is living in it, and there’s also no “gift-over clause” that specifies what should happen if any of LKY’s children die before him. (Both these points are moot now, since Lee Hsien Loong has sold the house to Lee Hsien Yang, and LKY did die before all his children.)

What seems to have happened is that Lee Suet Fern had forwarded the draft document without realising that it wasn’t actually the final-final text. In the judgment, it’s observed that she’d once had a more updated version of the document, since she’d tidied up some typos before LKY executed his First Will in 2011. In 2013, though, she’d sent an older version, thinking that it was the right one.

Did LKY know what he was signing?

Despite this boo-boo, it does look like Lee Kuan Yew did know what he was signing.

According to a contemporaneous note prepared by one of Lee Suet Fern’s colleagues who was present when LKY executed his Last Will, he was “certainly lucid”, and had “read through every line of the will and was comfortable to sign and initial at every page, which he did in our presence.”

Furthermore, two weeks after executing this Last Will, LKY himself prepared and executed a codicil to it, to do with bequeathing a couple of carpets — possibly including this one — to Lee Hsien Yang. LKY instructed his personal secretary to retain the original copy of his Last Will, along with this codicil, in her office. A copy was sent to his lawyer, Kwa Kim Li.

The Court of Three Judges also took into consideration that “while [LKY] had previously changed his wills several times, after the Last Will was signed, he was content with it. He lived for more than a year after executing it and did not revisit it, apart from providing for the bequest of two carpets to Mr [Lee Hsien Yang] in the Codicil.”

In other words, even though LKY didn’t actually revert back to his First Will as he’d wished, he had still been satisfied enough with what he’d executed as the Last Will that, apart from the carpet thing, he hadn’t seen the need to change anything anymore.

After LKY’s death on 23 March 2015, Lee Hsien Yang and Lee Wei Ling were appointed executors of his estate. According to Lee Hsien Loong, the Last Will was read to the family on 12 April 2015, during which there was a dispute between the brothers, which prompted him to look up old family email correspondences that he brought up in the statutory declarations to the ministerial committee. Lee Hsien Loong also said that he’d obtained copies of his father’s six previous wills in June 2015, allowing him to compare them.

Despite this, probate was extracted without opposition in October 2015. “I did not challenge the validity of the Last Will in court because I wished, to the extent possible, to avoid a public fight which would tarnish the name and reputation of Mr Lee and the family,” Lee Hsien Loong said in his statutory declarations. (This is ripe for one of those ‘How It Began — How It’s Going’ memes.)

What did the Court of Three Judges say?

In its judgment, the Court of Three Judges disagreed with the Disciplinary Tribunal, finding that there was not an implied retainer between Lee Suet Fern and her father-in-law, and that Lee Kuan Yew did not view Lee Suet Fern as his lawyer in this matter.

One might have thought that would be the end of the matter — if there’s no implied retainer, and Lee Suet Fern wasn’t acting as LKY’s lawyer, and LKY was content with his Last Will, then what’s the problem?

But the Court of Three Judges also noted that Lee Suet Fern is a very experienced lawyer, and that some of the alternative charges brought by the Law Society were framed in a way that did not require a solicitor-client relationship, because they used the “catch-all” provision in the Legal Profession Act that just refers to “misconduct unbefitting an advocate and solicitor”.

The court found that, while there was no dishonesty in her dealings with her father-in-law, Lee Suet Fern should never have claimed in her email that the attachment (i.e. the draft document) was the same as the First Will, since there was no way she could have actually known that — she didn’t have a copy of the executed First Will in the first place, so she couldn’t have compared it with the document she’d attached.

While this might have been excusable in the initial email, when Kwa Kim Li had been looped in — and therefore could be reasonably expected to be the one whose duty it was to double-check that it was indeed the right document that LKY intended to execute — the Court of Three Judges said that once Kwa was out of the picture, Lee Suet Fern, as an experienced lawyer, should have known to be much more careful and meticulous, instead of doing what her husband asked. Because of this failure to check, LKY probably ended up executing a will that wasn’t exactly what he’d intended, even if he was still content with what he did end up executing.

The court noted that “the harm caused in this case was at the lower end of the moderate range”, since the Last Will and the First Will were “materially similar”. But they also said that was just “fortuitous”, and that the “potential harm could have been far more severe than the actual harm that eventuated”. So while they felt that a striking off would be “disproportionate”, they decided that a 15-month suspension was in order.

What are Singaporeans to think?

All this drama about multiple wills and emails bouncing back and forth has been difficult — and also, let’s be honest, boring — to follow. Also, most of these details are private family matters; it’s none of our business how LKY wanted to split his estate between his kids, nor is it a matter of national concern how the kids are now tussling over the family home. It’s only become relevant to Singaporeans because public servants and institutions like Cabinet ministers and the Attorney-General’s Chambers have waded into the fray.

I do, however, have some comments/questions that I think are relevant in cutting through all the confusion to points that do concern Singaporeans:

- Lee Hsien Loong said that he did not challenge the validity of the Last Will in court, and allowed probate to be granted, because he didn’t want to air the family’s dirty laundry in public. Sure, I can see that. But if he didn’t express any opposition to probate being extracted — which would be the right time and place to raise concerns — then won’t he just have to live with the consequences of the Last Will being taken as the valid legal record of Lee Kuan Yew’s wishes, regardless of his personal misgivings?

That’s what any other Singaporean in that situation would have to put up with; who else would have the power to discuss concerns with the then-deputy prime minister, convene a ministerial committee, and make statutory declarations to that committee even after giving up on challenging the validity of the will in court? Are public resources and organs being used for a private family dispute? - The Lee siblings claim that it was actually on the urging of Lee Hsien Loong and his lawyer that probate was sought in 2015. They’ve asserted this multiple times, and I’ve not yet seen any refutation of this. If this is the case, then why did Lee Hsien Loong push for this, if he had misgivings? And if he did push for it, then shouldn’t he live with it (see point above)?

- Lee Hsien Loong’s personal lawyer in 2015, at the time of LKY’s death and when probate was granted, was Lucien Wong — the current Attorney-General (told you I’d come back to this). There was no complaint then by any of the parties, including by Lee Hsien Loong and his lawyer. Why, then, did the Attorney-General’s Chambers suddenly lodge a complaint against Lee Suet Fern with the Law Society in 2019? Why is a state organ getting involved in the private family matter regarding the preparation of a will that was already granted probate years ago? Again, are public resources and organs being used for private concerns? Do Singaporeans think this is appropriate?

One more observation: in his statutory declarations, one major point that Lee Hsien Loong appeared to be concerned with was the reappearance of the demolition clause in LKY’s Last Will. This is the concluding sentence of the summary that he posted on his Facebook page in 2017: “[Lee Wei Ling] and [Lee Hsien Yang] claim that Mr Lee was not prepared to consider any option other than the demolition of the House. For that they rely heavily on the insertion of the Demolition Clause in the Last Will. In light of the troubling circumstances set out above [questions relating to the making of the Last Will], I believe it is necessary to go beyond the Last Will in order to establish what Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s thinking and wishes were in relation to the House.”

What the Court of Three Judges’ judgment highlights is that the difference between the text that LKY had intended to execute as his Last Will (i.e. the text of the First Will) and the text that he ended up executing as his Last Will (i.e. an older version of the draft of the First Will) related to who would bear the cost of maintaining 38 Oxley Road, and a gift-over clause. Both these differences are now irrelevant anyway, because Lee Hsien Loong has sold the house to Lee Hsien Yang, and none of LKY’s kids predeceased him.

Despite the mix-up that Lee Suet Fern has been suspended over, as far as the demolition clause goes, LKY’s “thinking and wishes… in relation to the House” were clear: he did intend to have the demolition clause in his Last Will.

Hopefully that clears it up for Lee Hsien Loong.

If you enjoyed this issue, please feel free to share it!

This newsletter is supported by its Milo Peng Funders, who sign up for subscriptions at US$5/month or US$50/year (or more, if you like). Please consider becoming a Milo Peng Funder: