I don’t think it’s going to surprise anyone that Altering States contains discussion of drug use, but this issue also contains mentions of suicide. If you would like to speak with someone or seek help, you can find an international list of helplines here and here.

On Wednesday morning (UK time) I woke up to the terrible news that Lee Sun-kyun, the Korean actor known for his roles in critically acclaimed dramas like My Mister and the Oscar-winning sensation Parasite, was found dead in his car. I won’t go into details, but all the reporting so far indicate that he died by suicide. He was only 48, and leaves behind a wife and two children.

Lee’s death has been linked in the media to him having been under investigation for alleged drug use. News reports say that he’d been questioned by the police three times—the final session lasted for 19 hours. He'd reportedly claimed that he’d been tricked into consuming illegal substances. Although the investigation hadn’t yet come to a close, it was enough to attract plenty of media attention and seriously damage his image—with professional repercussions.

This loss is bad enough, but it also made me think of Yoo Ah-in, another brilliant actor whose career and reputation has taken a serious hit due to drug investigations. Yoo is currently standing trial for charges related to incitement to destroy evidence and breaching the narcotics law. As KBS World reported: “At the hearing, the actor’s legal counsel admitted to marijuana use but claimed that much of the prosecution's case on the alleged use of propofol are not fully factual or exaggerated.”

News of the investigation into Yoo also triggered public furore, and was commented on as a sign of how little margin of error is allowed to idols and celebrities in South Korea. They’re often treated as if they exist on a different plane, and expected to live up to unreasonable standards. The public’s heart can be fickle, especially when directed by media outlets who scramble to make hay out of any sort of ‘scandal’ that can be conjured up.

Even before the police had come to any conclusion, Lee Sun-kyun had lost work and sustained damage on a long-standing reputation built after decades of hard work. For Yoo, the public outrage was at such a level that someone threw coffee at him on the day of an appearance in court in May 2023 and another person threw cash in his face after a pre-trial detention hearing in September 2023, telling him to “use this money in prison”. He, too, lost work, such as his leading role in the second season of the Netflix series Hellbound. Other projects were postponed or withheld from release even if shooting had already been completed.

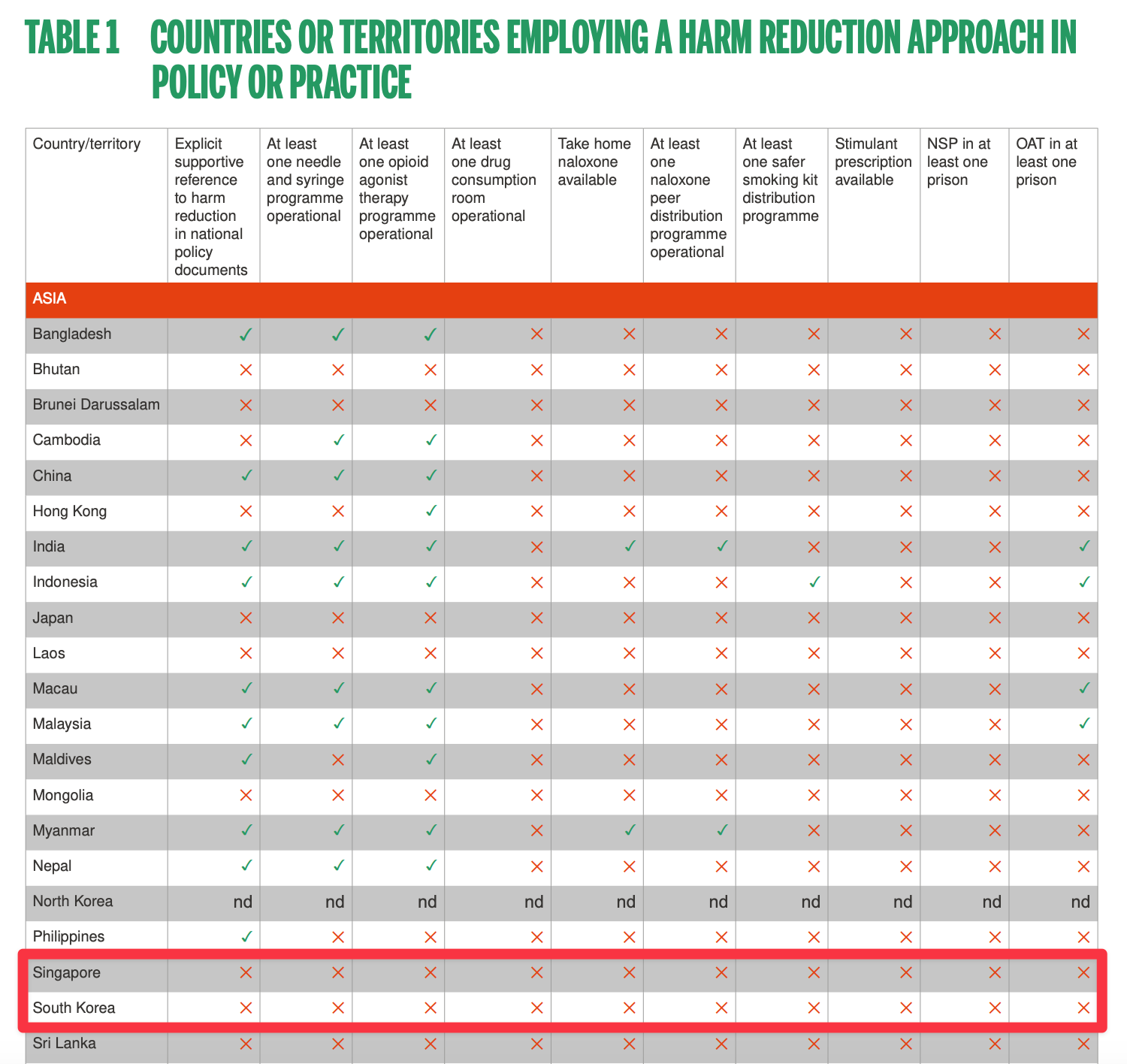

Situations like this don’t just come down to media sensationalism and celebrity culture. Politics and policy come into play too; the only reason the media can make such a huge ‘scandal’ out of a drug investigation is because there’s demonisation of drugs in the first place. Like Singapore, South Korea has very strict laws on drugs. For instance, both countries’ policing of their citizens’ bodies extend beyond their own borders; for both Singaporeans and South Koreans, drug consumption is illegal anywhere in the world, even if it’s actually decriminalised or legalised in that state or country. South Korea also has the death penalty for drug-related offences, although, unlike Singapore, they haven't executed anyone since 1997. This anti-drug stance doesn’t just lead to governments spending resources on policing—it also feeds into public stigma against people who use drugs (or are suspected of using drugs).

I’d followed Yoo’s case a little more closely before because I’m a fan of his work and was really sad to see the public reaction and the treatment he’d been subjected to. When I hear of people using drugs, I first wonder why: What prompted them to make that choice, especially if they live in countries with such tough drug legislation? What were they trying to achieve with their drug use?

I don’t know Yoo, of course, and have no way of knowing what motivated him, but it did strike me that one of the drugs he’s been accused of taking is propofol, a sedative that’s been classified as a controlled substance in South Korea since 2011. He has claimed that the use of propofol, as well as other substances, were for medical purposes, but even if he did consume it for other reasons, a sedative like that doesn’t strike me as the sort of substance someone would go for if they were well and happy and thriving. (For reference: a study of 38 propofol users in South Korea found that users reported using the substance for "stress relief and the maintenance of a sense of well-being".) How terrible, then, for a police investigation, public condemnation and a cratered career to be the response to someone who might already have been struggling in the first place.

Both Lee Sun-kyun and Yoo Ah-in were fantastic at their jobs. I don’t know what either of them really were/are like as people but I mourn the loss of Lee's talent, and hope Yoo can make a comeback someday. But the significance and impact of these cases don’t just come from their celebrity status. The news of Lee’s death prompted me to write something, but it’s not fame and stardom that makes this issue matter. It’s also because super high-profile cases like this make me wonder what it might be like for someone who might not have the same amount of social/cultural cachet and resources as these established actors.

Again, like Singapore, South Korea doesn’t really do harm reduction when it comes to drugs. In Harm Reduction International’s flagship The Global State of Harm Reduction 2022 report, both Singapore and South Korea strike out completely in the table that lists the harm reduction approaches “in policy or practice” that countries adopt, which means there are limited avenues for people who use drugs to seek help. There aren't enough drug rehabilitation options in South Korea. But more resources are being put into law enforcement instead: in April 2023, South Korea’s President Yoon Suk-yeol announced that “the government will join all forces to win the war on drugs”, amid a surge in drug seizures. The government has also announced a new narcotics investigation unit.

Drugs and minors

It's worth acknowledging that part of the concern about drug use in South Korea, leading to Yoon's pledge to clamp down on drugs, were cases in which substances were sold to minors: for example, drinks laced with methamphetamine reportedly marketed to kids as helping them to study better. There are also reports of teenagers trading in prescription medicines like appetite suppressants.

It's of course very worrying that children are being exposed to substances. There are risks to substance use, and kids might not be able to fully appreciate these dangers and make informed choices. Politicians often use "think of the children!" narratives to get the public behind their War on Drugs policies, and it's not surprising that it sounds extremely persuasive. But the War on Drugs might not help minors that much either; as long as there isn't sufficient rehab infrastructure, and the default response is punishment, then the lives of minors who have used drugs can also be derailed by "zero tolerance" policies. We can see fears of this from reports that drug dealers who sold drugs to minors also blackmailed their parents with threats of reporting the kids to the authorities. This blackmail works because of the state's reaction to and criminalisation of drug use—the anti-drug rhetoric leaves parents terrified that their kids' lives will be ruined if law enforcement got involved.

Moving away from the War on Drugs doesn't mean leaving it open for anyone to sell or provide drugs to minors. There can still be regulations stipulating age restrictions and prohibiting people from selling to kids. It's not new: we already do this with alcohol and cigarettes. And of course, public education—in schools and elsewhere—about the risks of substance use, as well as where to seek harm reduction, help and treatment, is crucial regardless.

The investigations and/or prosecutions of celebrities like Lee and Yoo allow the authorities to show that they are doing something about drugs, but I wonder what message these cases send, and whether it helps. If even beloved, admired and awarded actors—who seem so much brighter and more beautiful than the rest of us—can seemingly be abandoned and ostracised in a heartbeat, what signal does that send to ordinary people who have their own struggles with substances and addiction? At this point, it doesn’t even really matter if the celebrities are guilty or not—the public backlash and outrage have already done damage.

I send my condolences out into the ether and hope it reaches the people who love Lee Sun-kyun the most. I hope Yoo Ah-in and everyone else caught in conflict with the law because of drugs, wherever in the world they might be, have support structures around them that can provide care and help with healing. I also hope that more of us will realise the harm that’s being done in the name of “fighting drugs” and “saving lives”.