Apologies for not sending the weekly wrap on time; there was a lot to wrap my head around yesterday. I'm going to keep things focused on two big items this weekend.

"Despite his activism"

On Wednesday, Zakir Hossain Khokan, a migrant worker and prominent poet in the local literary scene, revealed on Facebook that he'd been forced to return to Bangladesh after working in Singapore for 19 years because the Ministry of Manpower had suddenly decided not to renew his work permit. At first, they told him that he had an "adverse record" — later they said that this had been an administrative error and that he'd simply been "ineligible" for renewal. The reasons for this ineligibility were not made clear to him.

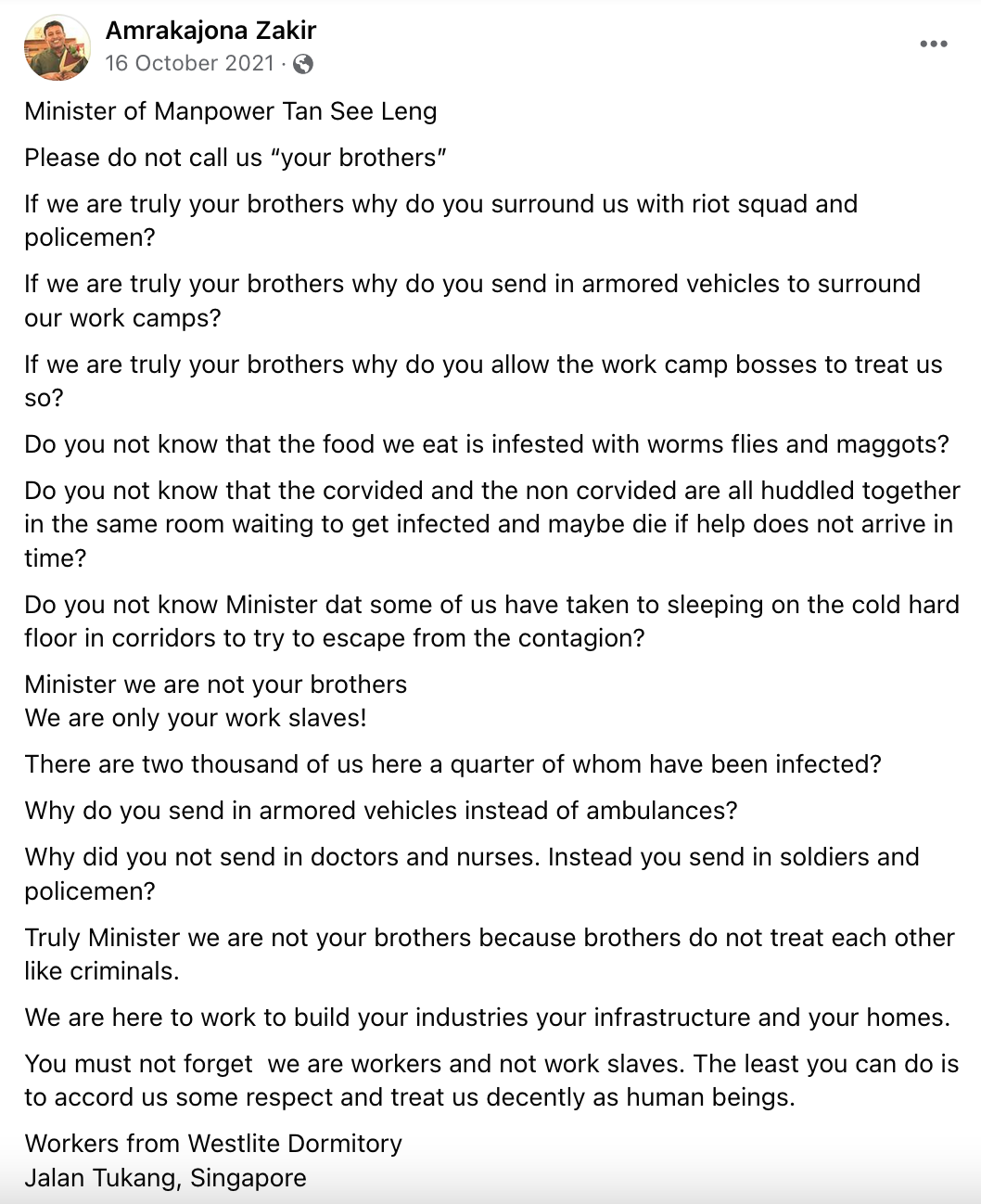

MOM's response came later in the day, in the form of a shockingly worded statement. Zakir, they said, had been "allowed" to work in Singapore a long time, and that they had previously renewed his work permit "despite his activism and writings". They took issue with this Facebook post that Zakir had written in October last year, in which he had called out Minister for Manpower Tan See Leng for referring to migrant workers as "brothers" when they're subjected to exploitative conditions and treated as security threats rather than equal human beings.

According to MOM, Zakir's post was a "false characterisation" of the situation. "There were no soldiers, let alone armoured vehicles, around," they said, adding that the post "could have incited migrant workers at Westlite Tukang and elswhere, inflamed their emotions and possibly caused incidents of public disorder."

What MOM is doing here is splitting hairs and throwing out speculative allegations to justify their decision to kick out a vocal migrant worker because they didn't like his social media post. Media coverage of the incident at the Westlite Jalan Tukang dormitory in October 2021 show that there was "a heavy security presence", with riot vans, police armoured vehicles, and riot police in intimidating gear. The fact that they were Special Operations Command and not actual military soldiers does not undermine the point that Zakir, a poet, was making in his post — that the reaction to the workers who the Minister for Manpower calls his "brothers" is to bring in the riot police as if they are threats to be managed rather than human beings who are justifiably angry, upset, and worried about their situation in a dormitory where there are insects in their food, and fellow workers infected with Covid in their rooms.

If anything were to "inflame the emotions" of migrant workers, it'd probably have been the poor living conditions they were subjected to, not Zakir's words. But if the authorities really thought that Zakir's post was an dangerous as they now claim, why didn't they take action then, rather than waiting for his work permit to lapse? If his post was false, why was there no POFMA order? Isn't POFMA meant to be for this sort of situation?

MOM ends their statement with: "Mr Zakir has been permitted to work in Singapore for a long time, though he was a long-time activist. His work pass has since expired. He cannot prolong his stay when he no longer has a job in Singapore. He has over-stayed his welcome." (emphasis added)

While they're denying that Zakir was targeted because of his activism, the statement still makes it clear that activism is not well-received by the authorities. It's a warning to other migrant workers who might speak out about the discriminatory treatment and exploitative conditions that they face. The government isn't interested in their voice, and doesn't want them advocating for themselves. They expect migrant workers to come here just to work, and to be silent and invisible the rest of the time (unless they are participating in government-supported initiatives, whereupon they're supposed to be effusive with their gratitude and enthusiasm).

This is a morally bankrupt position to take. Migrant workers are a part of the Singapore community, and they should be able to speak publicly about their own lived experiences, and organise themselves for better labour and living conditions. To kick Zakir out just because the authorities don't like what he has to say is bullying and unfair. And while this is a high-profile case because Zakir is well-known within the local literary scene, he certainly isn't the first vocal and critical person to be squeezed out (or ejected from) Singapore without transparent, fair reasons given.

Crossing the street = illegal procession

I'm still processing and trying to wrap my head around this, which is why this issue is coming to you later than usual.

Yesterday morning, Rocky Howe and I presented ourselves at the Bedok Police Division for questioning. We'd been summoned in relation to investigations, under the Public Order Act, into alleged illegal assemblies.

Today in Singapore, on my way home after an event, I was met at the MRT station by two police officers, who then got MRT staff to let us into a private (isolation?) room, just to hand me this letter summoning me for questioning re: "taking part in a public assembly w/o a permit". pic.twitter.com/K0gY0RZqaV

— Kirsten Han 韩俐颖 (@kixes) June 15, 2022

The two incidents that the police were saying were illegal assemblies were:

(1) When four of us sat on the public pavement outside Changi Prison late at night in March, hours before Abdul Kahar bin Othman was hanged at dawn. We chatted quietly, just keeping each other company so we wouldn't have to deal with the grief over a looming execution alone. I put up a Facebook post about this, which the police screencapped hours after it went up.

(2) Late at night on 25 April, four of us posed for photos outside Changi Prison ahead of the execution of Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam on 27 April. This is my Facebook post, also screencapped by the police.

It's ridiculous to me that the authorities expected us to seek police permission to hang out and take photos, but that's the position they're taking. Then things got even worse...

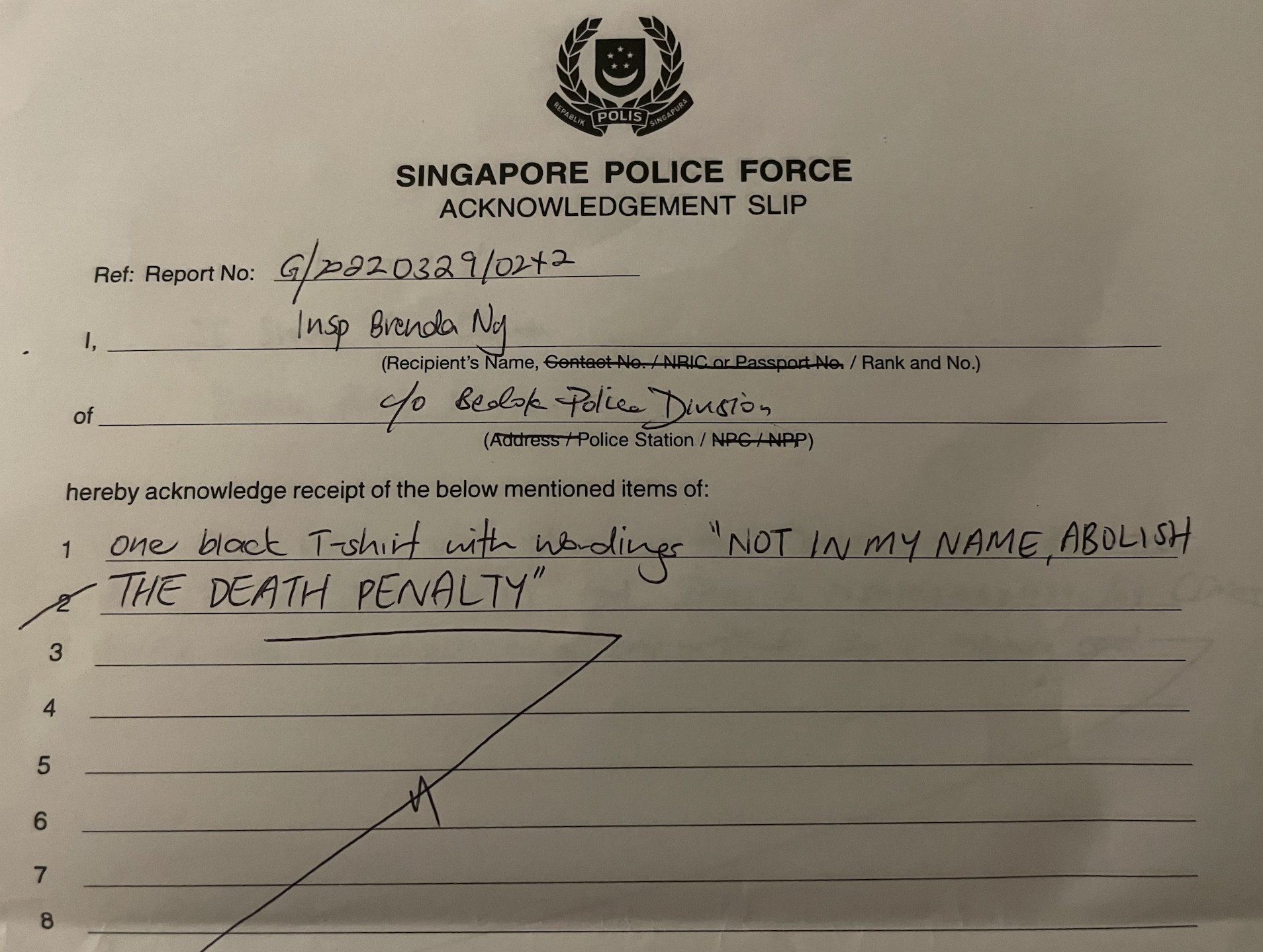

The police took issue with the shirts that Rocky and I were wearing yesterday. I was wearing the same black "Not In My Name: Abolish the Death Penalty" T-shirt that I wore in the photo we'd taken outside Changi Prison, while Rocky had shown up wearing a bright yellow shirt saying "2nd Chances Means Not Killing Them". We were flabbergasted to discover that, because we'd walked from the market across the street (where we had breakfast) to the police station while wearing these shirts, the police took the view that we had participated in an illegal procession. They then demanded to confiscate our shirts. I was made to call our friend Soh Lung, who was waiting for us in the foyer, to get her to go to the market to buy us new shirts, so that we could change and surrender our T-shirts. We weren't allowed to leave until that was done, which is the main reason why a one-hour interrogation turned into a three-hour affair. Soh Lung has written an account from her perspective here.

This should concern all Singaporeans because the Public Order Act is so broadly worded that the police are saying you can be participating in an illegal procession simply for walking on the street in a T-shirt that they deem "sensitive". I'd asked the investigation officer what about other types of shirts, like shirts with "save the panda" slogans, or other messages of support for other causes? Would walking around in public while wearing such shirts also constitute an illegal procession? I was not given an answer.

On top of that, the police, while seizing our phones, also demanded that I hand over my social media accounts. They wanted me to give them the logins and passwords to my Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram accounts (and, according to my notes, Gmail was mentioned too). I was also told by an officer, who identified himself as being from the cybercrimes response team, that after surrendering the accounts I shouldn't use them for the duration of the investigation, however long that might be.

I refused. I use social media for work, and communicate with people on those platforms. Some of these people turn out to be sources for my journalism work. I have a responsibility to all these contacts, and no amount of assurances that the police would be "professional" and handle things properly could dispel the serious privacy and digital security concerns I had. I had surrendered my phone (with most apps either logged out or uninstalled), but I could not hand over login details.

For this, I was told that I could get in trouble under Section 39(2) of the Criminal Procedure Code, which has to do with obstruction. This section bears the penalty of "a fine not exceeding $5,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or to both." I'm going to have to talk to a lawyer about this, but it's also a concerning that S39(2) is an arrestable offence, which means that the police can arrest me, search premises, and seize property without a warrant. So I walked out of the police station of more potential offences than I'd walked in with.

All this, stemming from two incidents in which there had been no disruption, danger, or disorder caused. In fact, in the first incident, we had already been leaving when the police showed up. In the second incident, we were only there long enough to take photos and didn't encounter anyone at all.

What a waste of resources. Such harassment wastes everyone's time while sending a signal about the state of civil liberties and human rights in Singapore. We're all poorer for it.

Thank you for reading this week! As usual, feel free to forward this issue and share it with people — it helps me get the word out about the newsletter.