The following is a lecture I delivered at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth tonight. It's closely related to my essay 'Singapore Will Always Be At War', which won the Portside Review Human Rights Essay Prize earlier this year.

In this lecture, I talk about Masoud Rahimi bin Mehrzad, the death row prisoner whose execution has been scheduled for dawn tomorrow. Just before our event began, I heard from TJC members back home that Masoud's 6pm court hearing had been suddenly cancelled. Masoud had been prepared to make oral submissions before the court, but didn't get the opportunity.

His family found out at 9pm that Masoud's application for a stay of execution has been dismissed. Barring a miracle—and I always hope for one even when I know how unlikely that is—his execution will be proceeding as planned. Despite pleas from Masoud, his family and members of the public, Masoud still has not been granted a video call with his father.

Last month, Fighting for Life was banned in Singapore.

Fighting for Life was a multimedia exhibition on the history of the anti-death penalty movement in Singapore, put together by volunteers from the Transformative Justice Collective, of which I’m a member. Refusing to provide TJC with the necessary classification to proceed with the exhibition, the Infocomm Media Development Authority said that Fighting for Life “undermines national interest”. They accused the exhibition of undermining the integrity of public institutions and the administration of justice, of presenting a misleading picture of Singapore’s capital punishment system, and of possibly being in contempt of court. We were given very few specifics about which bits of the exhibition were the problem. They said we’d have to make our own “assessment” about what to change—essentially, to self-censor—if we wanted to re-submit the exhibition for classification. But among the few things they did say they had issues with were letters written by death row prisoners.

To be a death row prisoner is to be already dead in the eyes of the state. Death row prisoners are not supposed to speak, to challenge or to fight. They are only supposed to wait, and, when the state decides that the time has come, to die.

In my essay, ‘Singapore Will Always Be At War’, I wrote about my country’s war on drugs and its victims. Today, I’d like to talk about telling the story of Singapore’s war on drugs and its victims, and how this storytelling is perceived and treated by my government as a threat.

Narratives are powerful. They set up the frames within which topics are discussed. They can tell people what to think but, even more importantly, they can inform how people think. Tell someone we’re at war, point out an enemy, and they’ll accept acts of violence that would be otherwise unthinkable. Reframe the issue as one of health, well-being and equality, point out that the ‘enemy’ is a fellow human being struggling with difficult circumstances, and suddenly we realise that different instincts and choices need to come to the fore.

The People’s Action Party, which has been in power in Singapore since 1959, has been dominating this game for a long time. The ruling party’s relationship with the local mainstream media has been described by Cherian George, a professor of media studies, as “freedom from the press”—from print to broadcast, mass media outlets don’t stray far from the official line and rarely, if ever, challenge those in power. When Singaporeans pick up the newspaper or turn on the TV for the evening news, we tend to see the world through the government’s lens, the words of PAP ministers regurgitated and blasted far and wide for national digestion.

Successive PAP governments have told Singaporeans for decades that drugs will ruin your life from the first hit, that drug traffickers are no different from mass murderers, and that the death penalty is vitally important for our collective safety and well-being. This message is drummed into the Singaporean consciousness, then reproduced through public opinion surveys in which citizens confirm that yes, they do indeed support capital punishment, and the government claims justification for its bloodthirsty policies. We’ve been riding this merry-go-round for generations, hundreds of lives crushed under its circular motion.

I was a good, obedient student in my childhood, and I learnt this story by heart. I rarely thought about the death penalty, but when I did, I thought only within the framing I’d been taught: a righteous war against crime and poison, one that Singapore could only win by doing what needed to be done. It was only when I got to see the death penalty regime up close that I realised the ‘truths’ I’d imbibed had actually been fiction.

My own experience demonstrates the importance of storytelling. While I thought of the death penalty only in abstract, black-and-white terms, it was easy to push aside niggling concerns about cruelty and killing and go along with the government propaganda. But once I acknowledged the humanity of the people on death row and witnessed their families’ struggles, the government’s narrative began to lose its power and I was forced to see things in an entirely new light.

There’s some data to back this up. An independent, comprehensive public opinion survey conducted in 2016 by researchers at the National University of Singapore, Singapore Management University and human rights group Maruah found that there was very little interest in, and knowledge of, the death penalty in Singapore among citizens.

Although a majority of Singaporeans initially indicated support for the death penalty, the survey found that “there was a large difference between the proportion of respondents who judged the death penalty to be the appropriate punishment when faced with the factual circumstances in the scenarios and the proportion who had said that they supported the death penalty in the abstract”. This was the case across the three offences that the death penalty is mainly applied to in Singapore: murder, firearms offences and drug trafficking.

“The overall findings of this survey show that while a majority of the public is in favour of the death penalty when the question is asked in general terms, it is certainly not an opinion which is held strongly or unconditionally,” the researchers concluded.

One lesson that I took from this survey was that the more information people have about the death penalty, how it’s used, and the cases to which it applies, the more likely it is for their support of capital punishment to at least waver. Singaporeans might not be persuaded to get rid of the death penalty just because other countries are abolishing it, but waking up to the realities on the ground in our own country can have a powerful impact.

Much of my contribution to the anti-death penalty movement has been about telling stories: bringing the lives and struggles of death row prisoners and their families to people, inviting them to shed all their preconceived notions about “criminals” and to see, really see, the person and the circumstances that have brought them to where they are. It’s what I tried to do with ‘Singapore Will Always Be At War’: pointing to men like Yong Vui Kong, Abdul Kahar Othman and Nazeri Lajim, making people read (and hopefully remember) their names. If they’re willing, I sit with the loved ones of death row prisoners, talking about their lives, their childhoods and their personalities. We talk about them as they are: Funny. Serious. Soft-spoken. Gregarious. Sensitive. Kind. Hot-tempered. Stubborn. Gullible. Moody. Lonely. Vulnerable. Traumatised. In pain.

Some family members don’t have many memories of them because they’ve spent so much time in reformative training as youths and prison as adults, but there are always anecdotes, flashes of temperaments and fears that show a whole person rather than just a “Prisoner Awaiting Capital Punishment”. I take these moments and put them into words, flowing them into stories that counter the dehumanisation the state imposes on those they have condemned. I ask—sometimes I beg—Singaporeans to recognise that the state is killing real people in all our names.

These are some of the people whose stories I, or other members of TJC, have told:

Kahar and Nazeri. Both were in their sixties when they were executed in 2022. Both lost their fathers at a young age and saw their families plunged into poverty. Both started using drugs when they were teenagers and struggled with addiction for the rest of their lives.

Kalwant, who raised his niece Kellvina even when he was little more than a boy himself. He called her “baby girl” right up to the last letter he wrote her before his execution. When I met Kellvina and her mother Sonia outside Changi Prison the morning of Kalwant’s long-drop hanging—a process meant to kill a person swiftly by breaking their necks—Sonia sobbed that the authorities had returned her precious brother to her “in pieces”.

Nagaenthran, or Nagaen, whose story generated momentum for the anti-death penalty movements in both Singapore and his home country of Malaysia. He’d been in prison for so long that, for most of their lives, his young nephews and niece had only known his voice from occasional phone calls. The first time they visited him in prison, he was overwhelmed by the noise—it’d been so long since he’d been in the company of children.

The government hates this work that I and my comrades at TJC do. “She is one of those who romanticises the people on death row,” K Shanmugam, Singapore’s minister for both home affairs and law, said to CNN about me in a recent article.

“Singapore might be an outlier when it comes to drugs, but it is a badge of honour we hold dear and part of our exceptionalism,” proclaimed a blog post on Petir, the PAP’s publication. “Perhaps when anti-death penalty activists stop their chase for virtue, they might start seeing drug traffickers for what they are. Scourge of the earth and proxy murderers who do not deserve our sympathy.”

“Scourge of the earth”. This is how the ruling party needs Singaporeans to think of death row prisoners in order to maintain their murderous policy. This is the only narrative they can allow to exist because it’s what’s needed to convince Singaporeans that the state must be vested with so much power it can even decide whether people live or die. And so they hate activists, hate that we remind the public of the humanity of those at the mercy of the capital punishment regime, hate that we are introducing complexity and reality and telling Singaporeans that they have the power to think for themselves, to oppose state violence, and to imagine a better, kinder, gentler society to live in.

Over the past few months the Transformative Justice Collective has been the target of “correction directions” issued under the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, better known as POFMA. (The latest one was waiting in my inbox when I arrived in Perth a couple of days ago.) This Act allows the government—and the government only—to issue orders demanding that targets publish “corrections” stating they’ve made “false statements” before providing the government’s version of “the correct facts”. The Minister for Home Affairs and Law has insisted that TJC publish notices saying that some death row prisoners “abuse the court process by filing last-minute applications” to try to avoid execution. It’s a criminal offence, with heavy penalties, not to comply with a POFMA direction.

One of TJC’s members has chosen to defy this oppressive law. Kokila, who’d written TJC’s post on an imminent execution in October, had republished the same text on her own Facebook page. When the government sent TJC a POFMA order, they sent one to Koki too. She has refused to comply and publish their outrageous “corrections”.

The government, claiming that they don’t target individuals for opposing the death penalty, says they’ve referred her to the POFMA Office for investigation. If charged, Koki will be facing a maximum penalty of a 20,000 SGD fine (close to 23,000 AUD), or imprisonment of up to 12 months, or both. When a group of us demonstrated our solidarity by republishing the original post and rejecting the government’s claim that it contained falsehoods, the government sent a POFMA direction to Meta, forcing the tech company to notify all users who’d seen our posts that it contained “false statements”.

It’s not the first time a big tech company is pushed into complicity in authoritarian control and it won’t be the last. (Not that they necessarily put up much of a fight.)

Stories have huge potential. Narratives can pose a threat to the interests of very powerful people. But they also have their limits.

If writing alone could change the world, I would write a volume for every prisoner, and no family would ever have to receive their loved ones “in pieces” ever again. But my words have failed so many times, and there has been so much death.

I’ve stood in an undertaker’s workspace, unable to tear my eyes away from the darkened, purple-tinted face of the man just hanged that morning. His cousin had requested my presence, had wanted me to take photographs of his family grieving over him, had wanted a witness to their pain.

A year later, I swept up the ashes of another man, depositing dust and bone in an urn that we brought out to sea in a little boat. Apart from the boatman, it was just me, his brother, father and best friend. We set him free, his remains vanishing quickly under the gently lapping waves.

I’ve been to so many funerals. At Nagaen’s funeral in his hometown of Ipoh, we formed a procession under the fierce glare of the sun. I held on tightly to the hand of Sangkari, the sister of Pannir, another Malaysian prisoner on death row in Singapore. In a voice low and hoarse with grief and anger, she asked me: “Do they feel satisfied, now that they’ve hanged him?”

I cannot speak to how the executioner, prison officers, lawyers, judges, police officers, government officials and politicians involved in sending Nagaen to his death felt. But I can answer Sangkari’s question in broader strokes: no, they are not satisfied. There is never any satisfaction when one is committed to an unwinnable war. There is only more killing.

I arrived in Australia in the first week of November. Since I’ve been away from home, there have been four execution notices, giving terrified families four to seven days’ advance notice of their loved ones’ killing. Three of the four men are already dead. Eight people have been hanged this year so far. My government’s murderous intent is clear.

This is Masoud. His family received an execution notice last Friday, informing them that the state intends to hang him this Friday. That is, tomorrow morning.

Masoud was only 20 years old when he was arrested. He has spent his twenties, and half of his thirties, in prison. Masoud loves reading; his sister says his cell is “like a bookshop”, because of all the titles he has requested his family bring him. He reads about theology, about psychology, about the law. In a context where local lawyers are often unwilling to take on post-appeal applications, Masoud has worked hard on legal arguments for himself and for other prisoners.

Tonight’s event began at 6pm. At the same time, Masoud was supposed to appear before Singapore’s Court of Appeal via Zoom from prison, to argue for a stay of execution. But just before this lecture, I got the news that his hearing had been cancelled. I don't know what means right now: are they going to give him a stay of execution and reschedule the hearing? Or will his case get dismissed and his execution carried out as planned?

Singapore’s president, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, has already rejected his latest appeal for clemency. Outside of prison, many of us have spent the day frantically posting on social media and emailing anyone we can think of to appeal for attention, help and support—Masoud’s father, who lives in a remote part of Iran and is in poor health, has not been able to make it to Singapore in time to see his son in person before the end of the final visit facilitated by the prison this afternoon. Masoud’s sisters, who are in Singapore, have been begging the prison to allow father and son a video call so they can speak to each other, possibly for the last time. The prison authorities have so far refused. I can’t understand why, since the fact that he was meant to appear before the court by Zoom clearly demonstrates that the facilities are available. But every time I think I’ve seen all the cruelty the death penalty can inflict, I discover that there are always more ways to deliver pain.

This week, Masoud’s family asked if he had a message to share with the world outside prison. He wrote a letter:

“Trusting God’s will does not mean we stop actively enjoining Goodness and standing up against injustice. Surrendering to Allah does not mean we stop trying, it means we stop thinking we can control the outcome of the choices we make. By surrendering, we let go of how we think things should be, and become flexible, to move with the breeze of Allah’s decree.”

As a writer, a storyteller and a human being, I bear witness to this brutality and feel the impotence of my words. I have written thousands—tens of thousands, possibly even hundreds of thousands—of words over fourteen years, yet the killings continue. And I am not the only storyteller in Singapore; there are other activists, writers, playwrights, poets, filmmakers, artists, actors, musicians, all trying in their own way to bring the death penalty before people’s eyes.

It is clear that storytelling is important, but not enough. The process of storytelling is only complete when a story is read or heard, but when it comes to human rights, justice and the death penalty, we also need people to act. Each person on death row has a story, but they aren’t just stories. They are people who have struggled, who, like Masoud, have fought tooth and nail with all the strength they have to live. They live in conditions of severe isolation and restriction. They do all they can for themselves, and for one another, in extremely challenging conditions.

Every effort they make inside should be matched by equal or greater effort by us outside, where there are so many more resources, options and opportunities. Where there is so much power and agency already inside each of us, if only we would just exercise them.

People often tell me that we activists are so brave, so strong, so incredible. I appreciate the sentiment, but we’re not the special breed of human that others seem to think we are. We’re not fearless or tireless. We are actually very, very tired. Within the anti-death penalty movement in Singapore are people who have risked, and continue to risk, their reputations, jobs, money, mental well-being, or even their freedom. We’re afraid and anxious and have probably—and by "probably" I mean "definitely"—had more than enough trauma exposure to put us in therapy for the rest of our lives. But we persist because we must. And we cannot fight this fight alone.

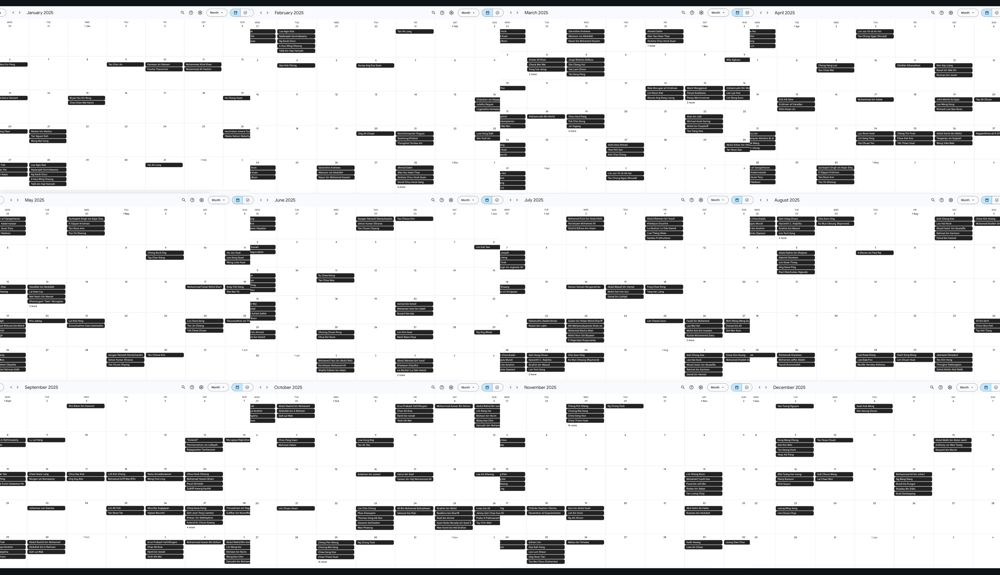

Every black box on this calendar marks the anniversary of a hanging that took place in Singapore, from October 1965 until today. Not every execution has been recorded in this calendar, because there are some old cases for which we don't have the exact date. Some days have so many death anniversaries that the list is truncated in this view. Many of these executions were for drug offences.

I do not ask any non-Singaporean or foreign state to swoop in and ‘fix’ my country. As Singaporeans, we will work to build the country we want to see. But solidarity is powerful and necessary, and there are things you can do in your own communities and countries to make the world a better, more just place. You can become storytellers too—I’m sure many of you already are—and spread awareness of what’s happening in Singapore far further than activists in Singapore can on our own. You can take action in a multitude of creative ways. You can decide how you, your communities, and your country should relate to states—and I'm not just talking about Singapore here—that do things like retain the death penalty, deprive their people of civil and political rights, or commit ethnic cleansing. You have more power than you know.

It is never easy to get authoritarians to give up their power or do the right thing. But it has been done before and I believe it can be done again. There will always be those of us who will work towards better futures, futures where no mother will ever have to be informed of her son’s impending murder via a notice bearing the prison letterhead. We do this work, and will continue to do this work, because even when it feels like Singapore will always be at war, we must also remember that Singapore must always have hope.

Thank you for reading. Feel free to share this newsletter, and this piece in particular, with your friends and family by forwarding this email.