I recently wrote about how humanity, empathy and compassion are especially important when fighting the death penalty.

An overhaul to adoption laws

This isn’t this week’s news — it actually happened earlier this month. It was absolutely my fault for missing it out; I knew it was a big deal for same-sex families, but hadn’t read up enough about it in the flurry of activity that was my early May.

The Adoption of Children Act 2022 was passed on 9 May; it replaces the Adoption of Children Act 1939 and extensively changes adoption laws and regulations. Under this new law, same-sex couples aren’t considered eligible to apply for adoption: Section 4 states that only couples whose marriages are recognised under Singapore law (they also have to be habitually resident in Singapore, and at least one partner has to be a citizen, or both of them need to be Permanent Residents) and individuals who are citizens/PRs and resident in Singapore are allowed to adopt. “This means that only a man and a woman married to each other can apply together,” said Masagos Zulkifli, the Minister for Social and Family Development, in Parliament.

He also said: “The Government has also stated that it is a matter of public policy that we do not support the formation of same-sex family units […] We reiterated in January 2019 that we do not support the formation of same-sex families through processes such as adoption. These public policies will be taken into consideration when determining suitability to adopt.”

While it wasn’t easy for same-sex couples to adopt before, this clearly removes that possibility. It adds to the pain that queer families already deal with, living under a system that denies their existence and love in very real ways.

I’ve heard rumblings of people trying to find a “bright side” to this, and speculating that this move is about appeasing the conservatives and paving the way for the repeal of Section 377A, which criminalises sex between men and legitimises censorship and discrimination against the LGBT community. While acknowledging that my views and feelings on this issue should take the backseat compared to what LGBT people in Singapore feel about all this, I have to say that I don’t understand that theory. Sure, Section 377A needs to be repealed, but isn’t it still horrible if the road to repeal is strewn with other legislation that denies the rights of LGBT people and their families? If the government continues appeasing conservatives in ways that materially impact LGBT people’s lives, families, and choices, what sort of victory would the repeal of Section 377A be? In any case, while there has been a bit of lip service about LGBT people here and there — in a way that might maybe perhaps hint at some possible inching towards repeal of Section 377A — we haven’t seen that much to suggest that the government really cares about LGBT equality, while we’ve seen a lot to suggest that, when push comes to shove, LGBT rights can get shoved under the bus.

Who wants to manage a Workers’ Party town council?

No one, it seems.

The Sengkang Town Council has announced that they will manage all divisions within it directly, without a managing agent. They’d put out a tender for bids that open on 8 April and closed 29 April, but there were zero bids. As it stands, Anchorvale is already being directly managed, whereas the Buangkok, Compassvale and Rivervale divisions are being managed by EM Services until 31 January next year (a contract inherited from Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC and Punggol East SMC).

Why doesn’t anyone want to work with Sengkang Town Council? (This, of course, isn’t the Workers’ Party first brush with town council-related woes: there’s also the Aljunied-Hougang Town Council [AHTC] drama.) According to EM Services, it’s because the “labour market is very tight these days”, so they have difficulty finding the right people with the “relevant skill sets” to allow them to make a bid in this tender. Sure. 🤨 I wonder how many other town councils might run into this problem of not being able to get a managing agent.

Checking in on POFMA

POFMA, the anti-“fake news” law, came into force in October 2019. How has it been used then? Singapore Samizdat, run by the brilliant Teo Kai Xiang, did a deep dive. (He’s also written an academic journal article on civil society responses to POFMA.) The piece provides valuable data, scrutinising the sort of claims that have been targeted by the law, who gets targeted the most, and who invokes the law the most.

Entry denied for Indonesian preacher

Abdul Somad Batubara, an Indonesian preacher, was blocked from entering Singapore on Monday (16 May 2022) and turned back to Batam. The Ministry of Home Affairs said in a statement that he preaches “extremist and segregationist teachings” that are “unacceptable” in Singapore. For instance, he has made comments denigrating followers of other religions, such as Christianity. Following this, the social media accounts of multiple government agencies and political office-holders were spammed by Somad’s angry supporters.

The prison correspondence case: a refresher

I wrote about the prison forwarding correspondence in 2020. This is at the heart of an ongoing civil case filed by 13 prisoners — 12 are currently on death row, and the 13th is Gobi Avedian, whose death sentence was set aside in October 2020. It's also the case that Datchinamurthy is part of; a day before his scheduled execution, he'd argued before the court that he should not be hanged until the conclusion of this case, and was granted a stay of execution.

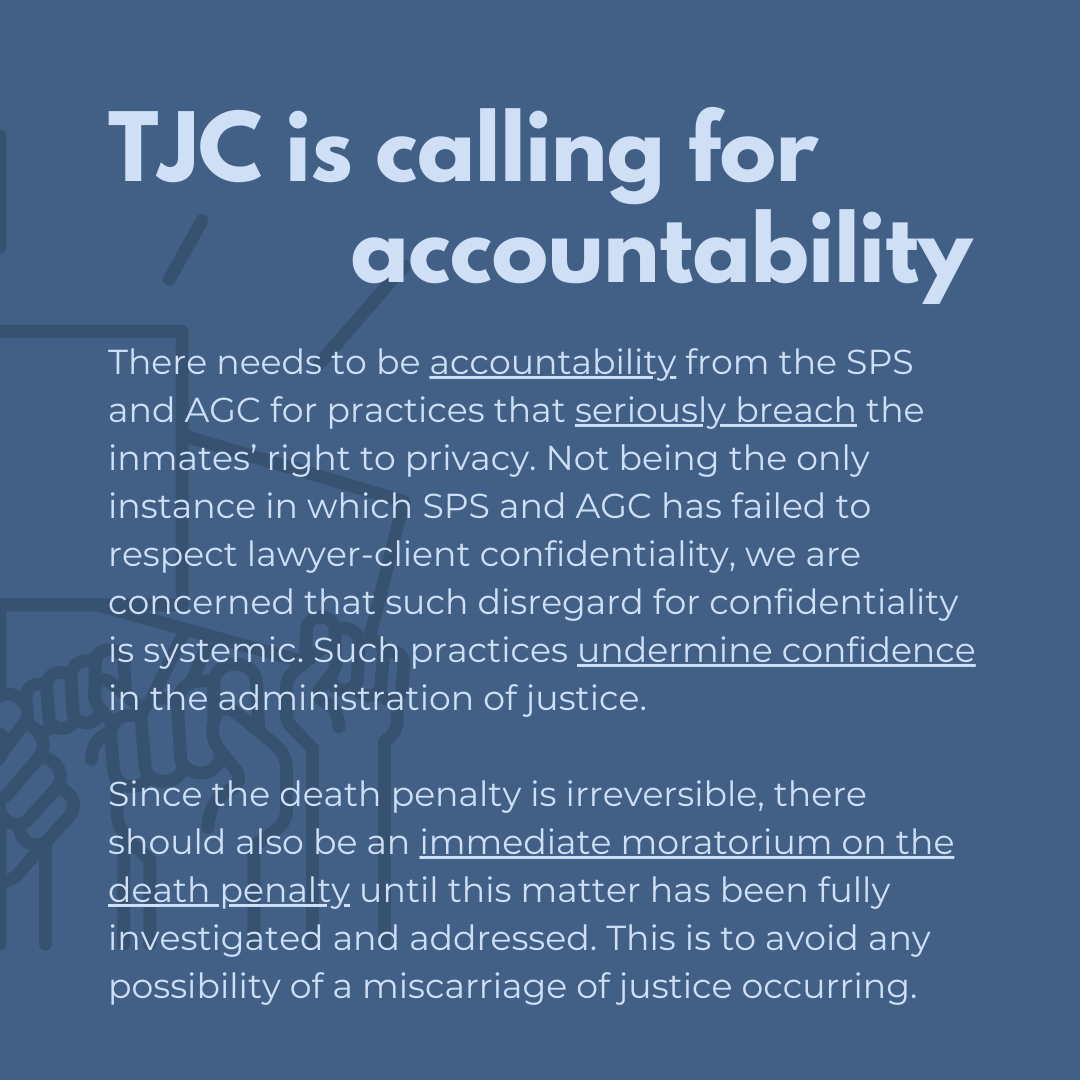

Here are some graphics from the Transformative Justice Collective about this prison correspondence case:

Checking in on the neighbours

🇧🇩 🇮🇳 🇵🇰 🇱🇰 This isn’t about Southeast Asia, but important nonetheless. This report examines the use of capital punishment for rape in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. From the executive summary:

“The introduction of capital rape laws in these four countries is a superficial response to a crisis, motivated by a political desire to be seen to be doing something about the perceived impunity of rape perpetrators. Our research found no evidence that the governments of the countries examined in this report were, in expanding capital rape laws, motivated by any serious desire to deliver justice to rape victims or to prevent rape. Rather, the introduction and expansion of capital laws has been justified on the basis that governments had ‘listened’ to public demands for harsher penalties for rape, with sensationalised media reporting construed as representative of the will of the people.”

Thank you for reading this week! As always, please help me spread the word about this newsletter by sharing it widely.