Altering States is a secondary newsletter that I run within We, The Citizens, focused on drugs and drug policy. It's irregular and always free. When you subscribe, you can choose either We, The Citizens or Altering States, or, better still, both!

From now on, I’m going to try to send out Altering States wraps on the last Thursday of every month, covering drug and drug policy-related news that didn’t warrant an entire newsletter of their own.

(1)

Harm Reduction International has published their latest report on the global state of the death penalty for drug offences. Let’s start with the basics: a quote from the foreword written by Morris Tidball-Binz, the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions:

People should never be sentenced to death, least executed, for drug offences. This practice is contrary to international law and standards as drug offences do not meet the definition of ‘most serious crimes’ to which international law requires the death penalty be limited to, in retentionist countries.

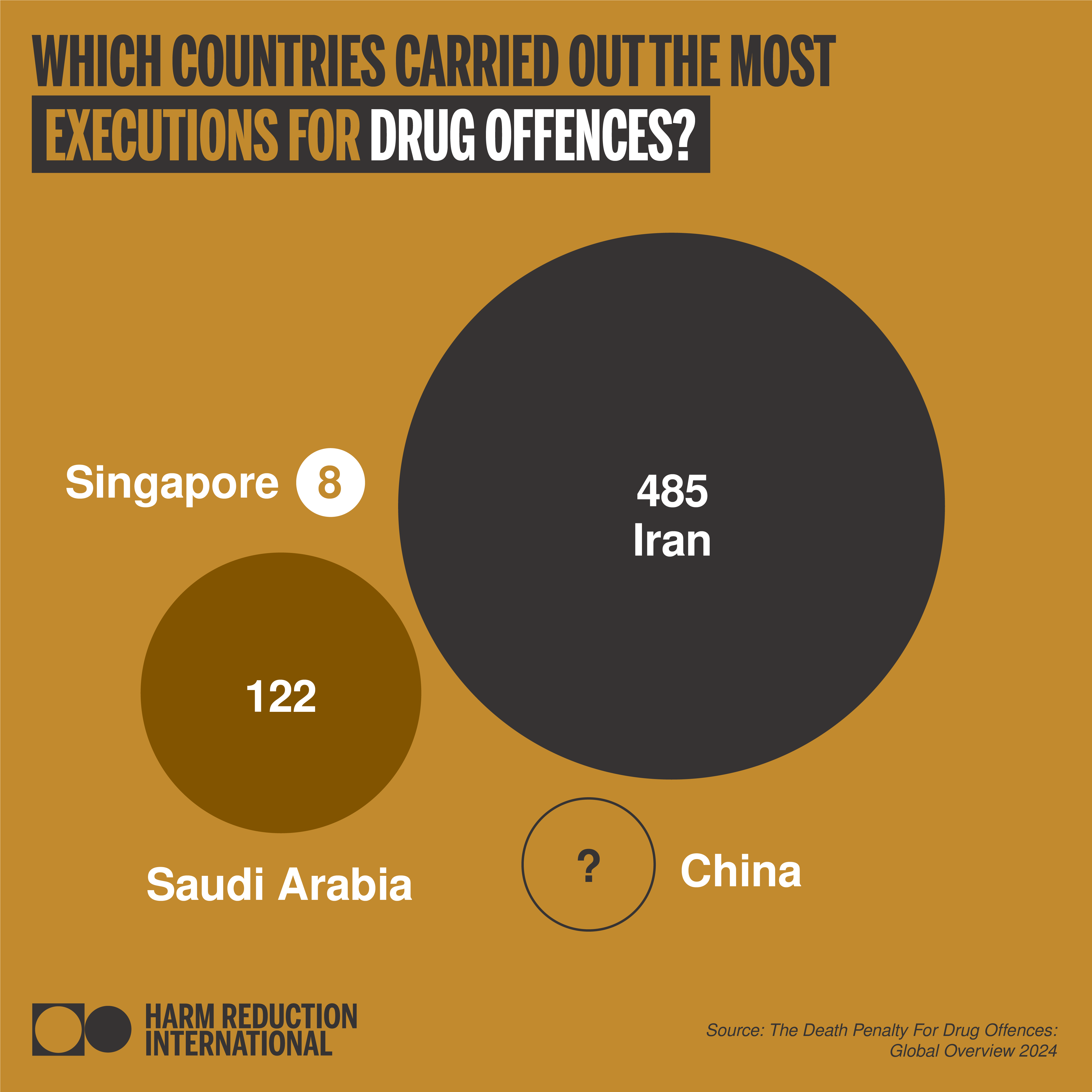

At the end of 2024, only 34 countries in the world retained the death penalty for drug offences. The number of drug-related executions has reached what HRI describes as “crisis levels”: 32% more in 2024 than in 2023. The 615 documented executions don’t even include the number of drug-related executions in China, North Korea and Vietnam, where such data is unavailable.

As HRI observes, it’s just a tiny group of countries that’s “responsible for an incommensurate number of executions”. Singapore is one of them, of course. We’re categorised as a “high application state”, putting us in the company of countries like China, Iran, North Korea and Saudi Arabia. (Malaysia is still on the list for now, but now that they’ve abolished the mandatory death penalty and loads of prisoners have had their death sentences set aside, I expect them to drop off this table in next year’s report.)

(2)

Earlier this month, Josephine Teo, the Minister for Digital Development and Information and Second Minister for Home Affairs, addressed the 2025 DrugFreeSG Champions Conference. It was generally the usual narrative: drugs are terrible and harmful and the global drug situation is worsening, so let’s buckle up and double down on our drug war. But Teo also paid special attention to one thing: young people consuming cannabis.

Government surveys have been finding that younger Singaporeans have “more permissive attitudes towards drugs”. This is seen by the authorities as a Big Problem that needs to be whacked hard with more anti-drug propaganda. Teo lamented the spread of “misinformation” about cannabis:

There are all kinds of ridiculous claims, for example: “Cannabis is natural, so it must be safe.”; “It is legal in other countries, so how harmful can it be and why must we take such a tough stance in Singapore?”; or “Cannabis is not very different from alcohol or tobacco. And since it’s not against the law once you reach a certain age to consume alcohol and to smoke a cigarette, why should it be so problematic that we consume cannabis?”. These assertions, however, cannot be further from the truth.

The science on cannabis is very clear and it is compelling: cannabis is addictive, with far-reaching and irreversible health effects.

I find this a rather strange statement to make, because alcohol and cigarettes are also “addictive, with far-reaching and irreversible health effects”. Yet we don’t criminalise them; we just enforce regulations related to their contents, import, distribution, sale and use.

Teo goes on to talk about the risks and dangers of cannabis, including “physical detriments such as headaches and nausea” and also “psychosis, memory issues and mood swings” plus “a person’s ability to think clearly and function normally”. Again… I think alcohol does this too.

I’m not here to say that there are no risks to consuming cannabis or that it’s perfectly safe. As with any substance, there are risks and benefits—the key is to be informed and clear-eyed about what they are before we make decisions about what and how we want to use. It’s not clear to me what good is really being achieved by arresting kids as young as 13 for using cannabis.

(3)

Since we’re on the subject of cannabis, I’d like to do a little plug for Currents, my husband Calum’s newsletter and podcast series. In her speech, Josephine Teo said:

Closer to home, we have the experience of Thailand. Within six months of changing the law to decriminalise cannabis, the number of cannabis addicts quadrupled. The Thai government had then intended to re-criminalise the use of cannabis, but faced fierce opposition from those seeking to profit from it. And so that shows very clearly: once you decriminalise, you will find it very difficult to roll things back.

What’s the real situation? Is it true that the number of “addicts” surged or are people like Teo conflating use and dependency? Is recriminalisation the answer, or are there better ways to support well-being? Calum’s latest podcast is a two-parter with Kitty Chopaka and Gloria Lai, both experts on the issue, here and here. What really stood out for me, listening to these episodes, is how much thought, care and consideration is required to craft and implement a holistic, proportionate and evidence-based cannabis policy.

We often talk as if it’s a binary between a drug war and a free-for-all, but that’s simply not the case. Drug policy—like any other nation- or society-wide policy, really—needs to be tailored to specific contexts, based on reliable data and a commitment to addressing systemic and structural issues rather than taking shortcuts. Knee-jerk reactions are not only rarely effective but also often counter-productive; we need to recognise that sustained engagement, education and investment is needed to create robust policies that respect human agency while also mitigating risks and promoting well-being. And we need to be flexible and open-minded enough to allow these policies to change and evolve over time as we monitor and study and learn.

Calum also reviewed Weed Rules: Blazing the Way to a Just and Joyful Marijuana Policy by Jay Wexler, an American law professor and expert on cannabis legalisation in the US. A lot of Weed Rules is US-centric, of course, but learning about the history and experiences of other countries can also help us arrive at more informed conclusions about what we need in our own societies and countries. We might not be able to copy-paste solutions, but we can learn from other people’s mistakes and successes.

Learning and reflecting

This month, I'm looking at the Charter of Rights for People Affected by Substance Use that was published in Scotland at the end of last year. The document was put together by people affected by substance use, family members and carers, service providers and national drug and alcohol support organisations, so it's supported by both policy, research and lived experience. The process of developing this Charter was led by the National Collaborative, which is an independent organisation that's also supported by the Scottish Government. One of the purposes of this Charter is to "shift the power and change the culture from criminalisation and stigma towards public health and human rights… the so-called 'undeserving' coming to see themselves as 'rights-holders' and the service providers better understanding what their role may be as 'duty bearers'".

The Charter sets out key rights for people affected by substance use: the right to life; the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; the right to an adequate standard of living; the right to private and family life; the right to a healthy environment; the right to be free from torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment; and the right to be free from arbitrary arrest or detention.

As you can see, Singapore's war on drugs would breach quite a lot of these rights. In fact, this entire process—from the idea to draft such a Charter in the first place through to its development and final publication—is so incredibly different from our approach in Singapore. It shows how much further we have to go to adopt a people-centric and rights-based approach to drugs.

Thank you for reading! As mentioned above, Altering States will always be free to access, so please share this with anyone who you think might be interested. If you’d like to support my work, please consider subscribing to We, The Citizens or leaving a tip!