Parliament is dissolved and we’re heading into the election period proper. This year’s election is going to look really different from previous ones; in this special issue, I’d like to look at what this might mean.

As elections go, GE2011 was a great time to be a first-time voter. More seats were contested in 2011 than in previous elections, which meant that my family’s constituency actually got to vote. It was also the first election since social media really took off, giving Singaporeans a relatively new and free space to talk politics. I remember the hopeful, perhaps naive, speculation that perhaps the “climate of fear” was finally, finally, eroding. (Narrator voice: “It wasn’t.”)

I attended my first political rallies that year, stepping into stadiums and onto fields, winding my way through crowds and craning my neck to see the speakers on the stage. I was a volunteer for The Online Citizen then, so I was busy taking photos, taking notes, or texting updates. It was exciting and thrilling; Singapore as I’d never seen it before.

(A photo I took at a Workers’ Party rally in 2011.)

It’s a pity that first-time voters — and all the rest of us — won’t have this experience this year. With Singapore still grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, special arrangements and guidelines will see the bulk of the political contest shifting online.

Farewell for now, rallies

Physical rallies will be replaced with live-streamed e-rallies. On top of party political broadcasts, each candidate will also get three minutes of broadcast airtime. While walkabouts can and have resumed, safe distancing rules restrict social gatherings to not more than five people, and some have already had their names written down (ah, this is giving me flashbacks to my short-lived school prefect days).

Apart from the loss to Singaporeans, who already have so few opportunities to (legally) gather in physical spaces for political causes, the lack of rallies are a blow to opposition parties. With such a short campaigning period, these smaller (in relation to the ruling People’s Action Party) parties have traditionally used rallies to introduce their candidates and blast their messages to a large number of people in a small amount of time.

(A Singapore Democratic Party rally at Jurong East Stadium in 2011.)

Then there’s the emotional impact: the excitement, the passion, the momentum generated by people gathered to listen to speeches, heckle or shout encouragement, chat to other attendees, buy party merchandise, eat ice cream while sitting on the grass. The buzz of the atmosphere can make one feel bolder, braver, safer. This is something that’s going to be very difficult — perhaps impossible — to replicate, if people are just going to be sitting before laptop and television screens in their homes.

My experience of the past two elections were of coming together: gathering in spaces, meeting with people, discussions with friends and taxi drivers alike. This year, GE2020 will see us more atomised, unable to properly meet up, except on social media platforms. But it’s not the same.

The online arms race

I’m not the first to observe that an Internet election like this will benefit established, well-resourced parties the most. While it’s true that all parties and candidates can set up their own Facebook pages and profiles, we should all know by now that social media is not really a great equaliser.

Parties with the most established presence on social media, with the capacity and skill and talent (or, as the case may be, the money to hire the capacity and skill and talent) to keep the algorithms happy with the most optimised content, will be able to reach more people. Newer parties who are only just now trying to get their “like” counts and engagement up will struggle for organic reach, and paying to promote content, while not as eye-watering as purchasing a full-page newspaper ad, can still add up and burden the budget.

Conversations can get derailed and go on irrelevant tangents extremely easily online, especially if any party can mobilise large numbers of supporters or trolls to flood spaces for discussion (like comment threads). Legitimate questions and conversations can be drowned out with bad faith accusations, non-sequiturs, ad hominem attacks, or even just incoherent ramblings that go on and on. We’ve all seen threads like that, which suck all the motivation out of anyone who might actually have had something worth saying.

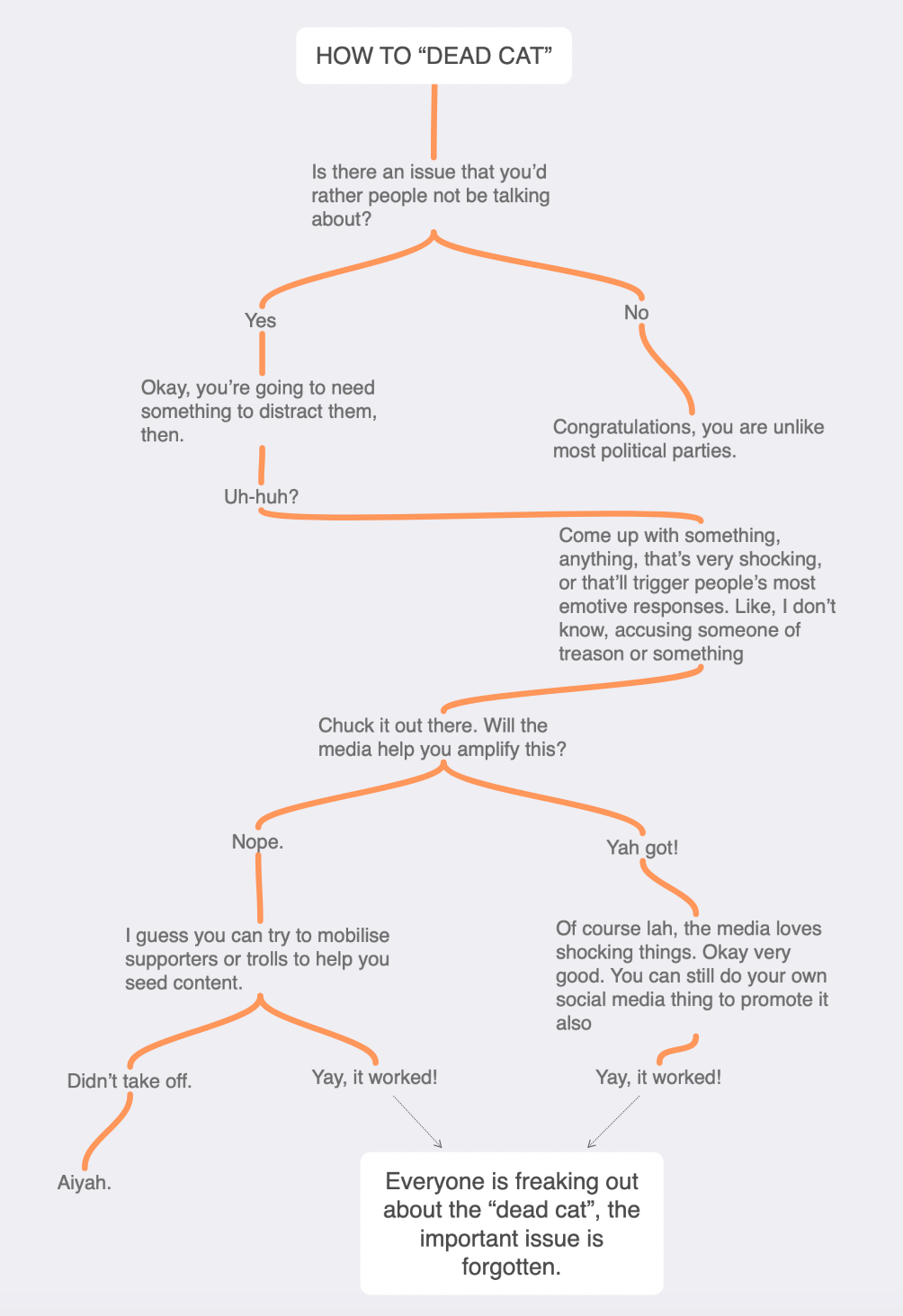

As mentioned during a webinar on this upcoming election, Singaporeans should also be vigilant and aware of tactics such as the “dead cat strategy”. This is where one party tosses something really shocking — i.e. the “dead cat” — into the public domain, which distracts everyone from more relevant and important issues, the discussion of which might not benefit them.

Another thing to be wary of as we become inundated with political advertising and other content: dog-whistle politics.

So what’s going to happen?

I’m not going to spend time trying to predict the outcome of the election, beyond what’s already fairly apparent: the PAP will win. At this point, speculation over the vote-share is pretty meaningless, since none of us really have a clue, and there will be no public opinion polls to help us.

Another factor that will shake things up a bit is that there appears to not have been any horse-trading this year. Previously, opposition parties met to carve up territory, so as to avoid multi-cornered fights that would likely split the vote and work to the PAP’s advantage. They don’t seem to have done that this year (paywalled), and the Progress Singapore Party is unapologetic about the possibility of there being multiple parties competing in the same constituency. There’ll probably be a three-cornered fight at West Coast GRC, for example, since both the Progress Singapore Party and Reform Party are eyeing it.

Although there’d been some consideration of opposition coalitions, it’s not really gone anywhere — the Reform Party, People’s Power Party, Singaporeans First, and the Democratic Progressive Party have given up on their bid to join the Singapore Democratic Alliance, and say they will have their own informal alliance.

What I hope to come out of this no-horse-trading election is that some of the parties might eventually recognise their own weakness/insignificance, and either bow out, or merge with other parties to present a stronger challenge. This might upset some people, but there’s just no point to some of these smaller opposition parties.

What should we do?

This election might look and feel different from any other, but the stakes remain the same: this is the time for Singaporeans to carefully consider the different parties and candidates vying for our vote, and to make an informed choice.

Someone recently asked me what advice I’d give to first-time voters. The question also came up during the webinar on the elections organised by CAPE and Academia.sg. Here are some things that come to mind:

Understand how the game works

If you missed the CAPE and Academia.sg webinar, I recommend clicking on the link above and listening to the academics who have devoted significant amounts of time to researching and studying Singapore’s politics, parties, and elections.

If you don’t already know, look up how Singapore’s electoral system works, so you have clarity about what Members of Parliament are supposed to do, and what you’re voting for. There are plenty of resources, from CAPE’s handy infographics to this GE crash course page to more detailed explainers.

Read manifestos (DO IT!)

I get it. Manifestos are not always super interesting. But it’s important that we scrutinise the platforms that parties are running on, and manifestos are how we know what they stand for, and what they are promising (or not promising) should they win. Most of us aren’t voting for the individual candidates we want to represent us, anyway, but for the party that they’re from.

Ask yourself what’s important to you

No one is a single-issue voter. Everyone has their reasons for why they vote, and the right to make their own decision. Think about what’s important to you, and try to find out where the candidates and parties stand on that issue — which brings us back to reading manifestos. If you aren’t satisfied, or can’t find what you’re looking for in the manifestos, you can also reach out to the parties and candidates via social media, email, etc. You’re entitled to ask questions — use that power!

Given the obvious public interest in all this, I’m continuing my practice of not paywalling content on the Substack site. Milo Peng Funders, though, will get election coverage delivered straight to their inbox for convenience. If you’d like to share this post with others, you can use the button below:

I’d like to thank all the Milo Peng Funders so far — your paid subscription helps me to continue working on this newsletter, and I really value your support! As we enter this election period, I’m planning to start Milo Peng Funder threads that will provide a safe (or, as safe as I can manage) space for us to ask questions and interact with one another.