This is We, The Citizens’s second GE2025 special issue. While WTC’s special issues are usually only emailed to Milo Peng Funders and are sometimes paywalled, GE2025 special issues will be made accessible to all. Please support this work by sharing this newsletter and subscribing/tipping if you can! Since April is WTC’s birthday month, there are also discounts off monthly and annual subscriptions—just click the preferred button below.

On Tuesday morning—yup, April Fool’s Day—Jolovan Wham will once again be appearing at the State Courts. He’s already been charged with five counts under the Public Order Act for participating in vigils for death row prisoners who were about to be executed by the state. Tomorrow he’ll find out if the prosecution intends to add more charges.

When the state targets an activist, what they’re trying to do is make an example of that individual—to mark them out as ‘bad’ or ‘criminal’ or ‘dangerous’, to make them seem radioactive so everyone will give them a wide berth. This is how they undermine movements, so that resistance remains small, scattered and easily quashed. But Singaporean civil society is learning and growing: we’re building more and more solidarity, refusing to fall into the divide-and-conquer trap by showing up for one another over and over again.

When Jolovan was charged in court in February, close to 30 of us turned up. We left the building together after his court mention and took some photos. Others have posed for photos in the same area before. We’ve seen plenty of journalists, photographers and videographers clustering around people there, too—the Workers’ Party’s Pritam Singh being a notable recent case—so it didn’t seem like a big deal. After that, we went on our way, leaving the State Courts standing as safe and secure as ever.

Singaporean civil society is learning and growing: we’re building more and more solidarity, refusing to fall into the divide-and-conquer trap by showing up for one another over and over again.

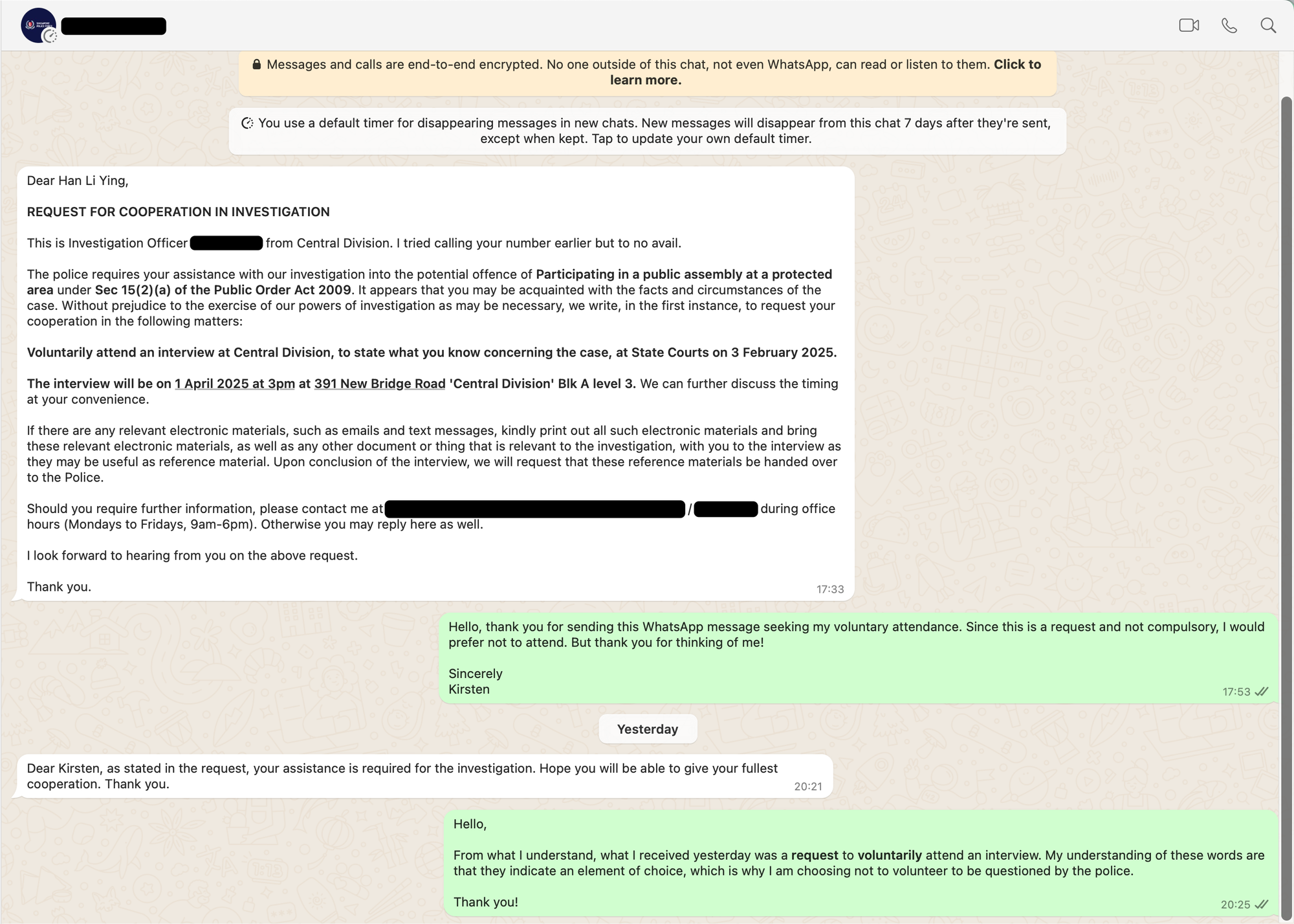

On Friday evening, I received a WhatsApp message from a business account with the Singapore Police Force logo as its profile photo. An investigation officer (or someone who identified himself as an investigation officer) wrote that the police “requires your assistance with our investigation into the potential offence of Participating in a public assembly at a protected area under Sec 15(2)(a) of the Public Order Act 2009”.

The message continued: “Without prejudice to the exercise of our powers of investigation as may be necessary, we write, in the first instance, to request your cooperation in the following matters: Voluntarily attend an interview at Central Division, to state what you know concerning the case, at State Courts on 3 February 2025.” (emphasis mine)

The officer wasn’t very specific, but unless the SPF’s position is that a bunch of people attending a public court session together is an illegal assembly, it appears as if they’re considering the mere act of taking photos outside the State Courts to have been “participating in a public assembly at a protected area”.

The problem with volunteering to be questioned

A request sounds pretty polite. But why should I volunteer to be interrogated about something that’s so clearly a waste of everyone’s time? Why would I volunteer to be harassed?

I've learnt this lesson the hard way. Back in October 2022, I received a phone call from a police officer asking me to present myself at the station. She refused to tell me what it was about, saying she could only tell me at the station. There was a little bit of to-ing and fro-ing—with plenty of uncertainty and confusion on my part—but I never found out what the matter was until I actually went down. It turned out that the officer, at the request of the Attorney-General’s Chambers, just wanted to hand me a conditional warning for alleged contempt of court. After all that mystery, the whole exchange only took a few minutes.

Why should I volunteer to be interrogated about something that’s so clearly a waste of everyone’s time? Why would I volunteer to be harassed?

When I challenged the conditional warning in court, my lawyer also brought up the way in which the police had conducted the whole affair. Why couldn’t they have just told me over the phone that it was about a conditional warning, instead of letting me speculate and worry about whether it was an investigation (or even arrest) that would disrupt the upcoming work and travel plans? I, through my lawyer, sought a declaration from the court that the police had no right to make me go to the police station in the way they did.

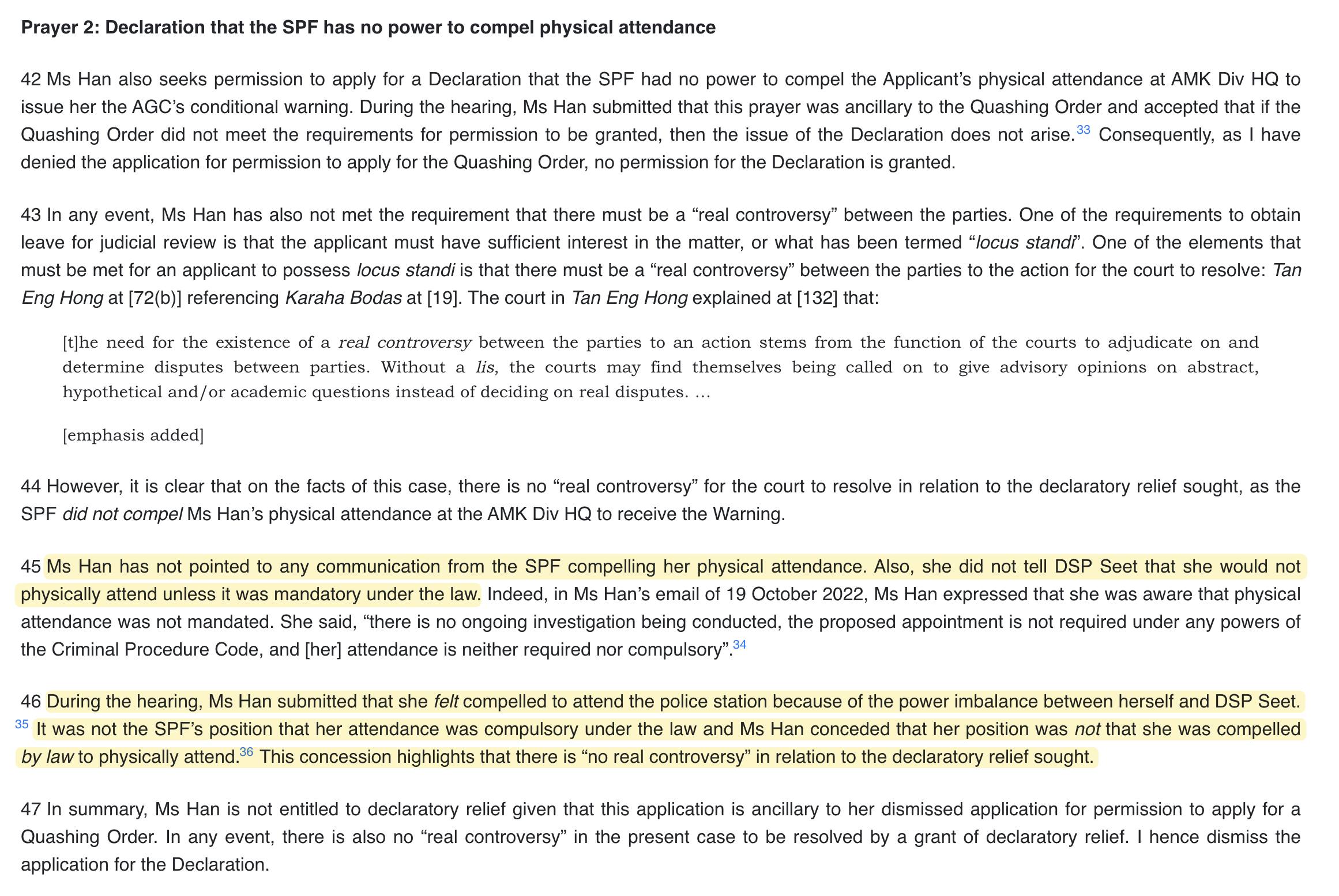

The judge refused to grant permission for such a declaration since he also dismissed the prayer for the conditional warning to be quashed. But he said that my situation hadn’t met the requirement of there being a “real controversy”, in any case, because the police hadn’t forced me to go to the station. “Ms Han has not pointed to any communication from the SPF compelling her physical attendance,” the judge wrote in his 2023 judgment. “Also, she did not tell DSP Seet that she would not physically attend unless it was mandatory under the law.”

He continued: “During the hearing, Ms Han submitted that she felt compelled to attend the police station because of the power imbalance between herself and DSP Seet. It was not the SPF’s position that her attendance was compulsory under the law and Ms Han conceded that her position was not that she was compelled by law to physically attend. This concession highlights that there is ‘no real controversy’ in relation to the declaratory relief sought.”

I’ve learnt my lesson. I no longer want to be told that, because I hadn't been explicitly forced, I'd willingly submitted myself to such treatment. If the police want something, they should be able to state—clearly and in writing—what it is that they want and what power they have under the law to demand or require it. They shouldn't be able to make "requests" and pressure people into obeying before claiming that it was all "voluntary".

That's not what "voluntarily" means

My exchange with the investigation officer—who, if not for other friends receiving the same “request”, I might have assumed was a scammer—over the weekend suggests that SPF has a rather poor understanding of the words “request” and “voluntarily”. After I told the officer that I preferred not to attend, his response was that my “assistance” was “required for the investigation”.

Well, which is it? Is it a request, or is it a requirement?

I’ve experienced a number of police investigations and witnessed many more. There’s a lack of clarity and consistency: I’ve been called in for questioning via phone call, or cops have shown up at my door with printed summons. Once, a couple of officers were so determined to put the summons directly in my hands that they met me at an MRT station where we were escorted by SMRT staff to a private room. I’ve also been handed such requests for voluntary attendance in person, or received summons in the mail or by email.

This time, I received a text via WhatsApp. But others, like the students under investigation for their pro-Palestine memorial, have experienced police officers showing up unexpectedly to search their residence, confiscate their property and even question them in their own homes. From the outside—and often even from inside the interview room—it appears confusingly arbitrary.

In many of these cases the alleged offence has been related to illegal assemblies prohibited by the Public Order Act. None of these cases involved any violence or harm. What is the protocol? What are the rules? What thresholds, if any, must be met before the police considers one course of action over another?

Legally, I know that the police has wide discretion to conduct investigations. Yet I can make no sense of why they act one way in some cases and another way in others. Meanwhile, we aren't allowed legal counsel during questioning to look out for our best interests’ and keep us informed of our rights.

Power and political rights

Nonsense investigations and confusing or unpredictable behaviour. This is how they use their power. The state, under the control of successive PAP governments, has stretched the Public Order Act to its most absurd extremes, wasting public resources on bullying citizens who refuse to stay silent and obey.

We are not allowed to grieve, we are not allowed to mourn, we are not allowed to express anger and horror in the face of relentless brutality, we are not allowed to challenge, we are not allowed to stand in solidarity.

It’s illegal to stand outside Changi Prison—or any public place, really—to grieve when the state kills a person in all our names. Police officers sometimes struggle to articulate what exactly is illegal and why, but it’s apparently illegal all the same and people have been investigated, issued warnings, or even charged.

It’s illegal to deliver letters to national institutions or government ministries as a group, especially if you’re holding particular umbrellas or wearing particular T-shirts. They’re not illegal—maybe, I think—if the group is umbrella-less and uncoordinated fashion-wise, because I’ve participated in such letter deliveries with no incident. It’s unclear why umbrellas and T-shirts transform a legal thing into an illegal thing. But people have been questioned and charged.

It’s illegal to arrange shoes and set up a memorial—with zero people in attendance—to mourn a genocide. The police will go over the CCTV footage and track down people they think were involved and search some of their homes and seize phones, laptops, even clothes.

It’s potentially illegal to be wearing the wrong T-shirt (?) in the wrong place (?) at the wrong time (?) I’m very confused about this one and I’m not the only one. In 2022 police officers confiscated the anti-death penalty T-shirts my Transformative Justice Collective colleague Rocky and I were wearing because they thought we might have constituted an illegal procession by walking from the hawker centre to the police station together. The AGC later advised that there was no offence. But when students put on shirts saying “THERE ARE NO MORE UNIVERSITIES IN GAZA” and walked from Novena MRT to the Ministry of Home Affairs, that was a problem.

And now, it seems as if it might also be illegal to show up and take group photos outside the courts.

We are not allowed to grieve, we are not allowed to mourn, we are not allowed to express anger and horror in the face of relentless brutality, we are not allowed to challenge, we are not allowed to stand in solidarity.

Simply put: Singaporeans are not allowed to defy.

The promise of openness

What does this have to do with GE2025? Everything.

Elections are the process through which we arrive at the government we’ll have for a term of up to five years. Even if there isn’t a drastic change in political power, elections can set the tone for our politics in the years to come. Look at how closely the PAP watches its share of the vote; it’s not just about winning, it’s also about how much they win and what they need to do to maintain their lead.

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong talks a big game about a “more open society” and starting conversations with “civil society leaders”. But what we see on the ground is completely different. I don’t know if he’s being dishonest or if he doesn’t have enough clout to keep the more hardline members of his party in line. Neither scenario is good. Neither will save us from a Singapore of increasingly petty authoritarianism. We can't rely on Wong or any single politician. We, as voters, can only rely on ourselves to send a message loud and clear about the sort of politics and leadership we want in our country.

Civil and political rights cut across all issues and are fundamentally about the space that we have to speak our minds and act in accordance with our consciences.

This isn’t just about the death penalty or Palestine or a bunch of activists whom you may or may not agree with. When our civil and political rights are suppressed or denied, we lose our ability to participate as active citizens on all issues—including the “bread and butter” ones often touted as more important and relevant to Singaporeans. The harassment and hostility currently directed at Singaporeans speaking out against capital punishment, Palestine and POFMA can just as easily be turned toward citizens who want to organise around issues like the cost of living, CPF or property prices. The hammer can come down—any time and on any issue—the moment people stop confining themselves to PAP-dominated “proper channels” and start engaging in ways that make the ruling party uncomfortable.

Civil and political rights cut across all issues and are fundamentally about the space that we have to speak our minds and act in accordance with our consciences. More than any NMP scheme, NCMP scheme, government-led “national conversation” or REACH portal, civil and political rights allow Singaporeans to claim our own space, discover our own power and live on our own terms.

This is why, for this coming GE2025, we must not be so easily swayed or bought over with empty promises of “openness” and “conversation” and “Forward Singapore”. Nor should we buy into the narrative that talk of rights and values are less important than “bread and butter issues” and municipal upkeep.

It’s all connected.

Thank you for reading this special issue! Please help me get the word out about WTC by sharing this newsletter.