Check out We, The Citizens’ spreadsheet compilation of party manifestos for this election.

It took me some time to build up to writing this issue. I needed to clear my head a bit and think about what I could write that would be useful, rather than just pouring disappointment, frustration, and heartache into your inboxes.

For those who need to be caught up…

The police released a statement earlier today to say that reports have been filed against Raeesah Khan, a Workers’ Party candidate for Sengkang GRC, in relation to social media comments she’d made. After consulting with the Attorney-General’s Chambers, the police have decided to open an investigation under Section 298A of the Penal Code, which states:

298A. Whoever —

(a) by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise, knowingly promotes or attempts to promote, on grounds of religion or race, disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different religious or racial groups; or

(b) commits any act which he knows is prejudicial to the maintenance of harmony between different religious or racial groups and which disturbs or is likely to disturb the public tranquility,

shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 3 years, or with fine, or with both.

What were these social media comments? Around the time the police reports were made — according to the statement, they were made on 4 and 5 July — pro-PAP Facebook pages also began circulating these particular social media posts of Raeesah’s, accusing her of trying to create racial divides:

(I’ve edited the screencap above to black out a tweet that was captured alongside Raeesah’s, as the author of the tweet has reached out to say that he would not like his tweet to be misconstrued and associated with all this.)

As you can see, one is a post Raeesah published in May this year, when Singaporeans were kicking up a stink about perceived double standards in the treatment of people (many of whom were white expatriates) breaching safe distancing rules at Robertson Quay, and the treatment of Singaporeans who have been penalised for such behaviour, as well as low-wage migrant workers who had their work permits revoked.

The other is a post Raeesah put up two years ago, expressing unhappiness about sentencing in the City Harvest Church case, where six members were found guilty criminal breach of trust. The six had been found guilty in 2015, but filed appeals, which resulted in the High Court cutting down their prison terms in 2017. The prosecution appealed for the original sentences to be reinstated, but the Court of Appeal maintained the original jail terms on 1 February 2018, a day before Raeesah’s post on Facebook. There was some public outcry that the convicted had got off too lightly — the sum, $50 million, was staggeringly large after all. This was acknowledged by Law Minister K Shanmugam in a speech on 5 February, who also said that the government agreed that the sentences were too low, and that legislation needed to be revised.

Given that neither post was made recently, people have questioned the timing of these police reports. Regardless of what the police do next, it’s likely that their statement has dealt a blow to Raeesah and her team’s campaigning in Sengkang GRC — if not the entire WP’s efforts. It’s another stick of dynamite thrown into the mix of an election that’s supposed to be focused on “serious life and death” issues, alongside quarrels about population figures, the NCMP scheme, and whether the PAP could have written the WP’s manifesto.

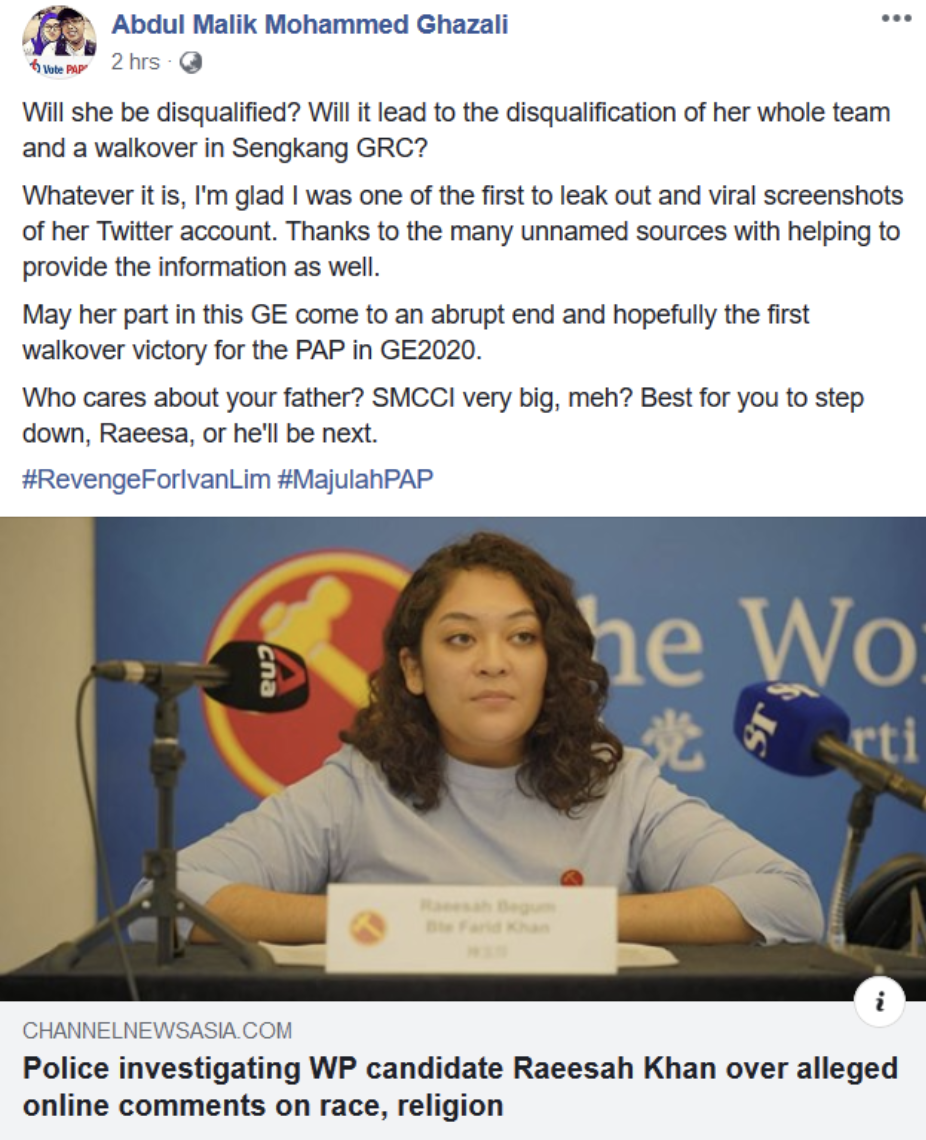

A PAP supporter has also posted publicly about how he had been among the first to dig out the posts and circulate them. He also seems to be making a threat against her father:

Raeesah has made a statement at an unscheduled doorstop saying that she’ll cooperate with any investigation. She also apologised to any racial group or community that had been hurt by her comments, saying that her remarks were “insensitive” and she regrets making them.

There is no such thing a “reverse racism”

One thing that I’ve already seen come up is cries of “reverse racism”, or racism against the Chinese who form the majority in Singapore. This is the likely at least part of the foundation for the reports against Raeesah, given that the police statement highlights her references to “rich Chinese and white people”.

I’d like to take this opportunity to state that there is no such thing as “reverse racism”, and provide as succinct an explanation as possible of why this is so:

Racism is a system of oppression. The thing about systems is that they aren’t caused by any single individual; they are built up over time and over generations. And because it’s something that develops over such a long time, it becomes entrenched in our society, and so normalised that we (especially those of us who belong to the majority race) don’t see it and don’t question it. Things simply become adopted as natural and logical, embraced as “common sense” knowledge, because we grew up with certain assumptions, stereotypes and prejudices that have become so commonplace they’ve gained the veneer of truth.

Yet this system of oppression exists despite our failure or inability to see it. As I wrote in a previous issue: “There’s ample evidence that systemic racism exists in Singapore—from the discrimination against Malays in the armed forces, to the inexplicable Ministry of Manpower rules restricting certain jobs to certain source countries (for example, people from South Asian countries can be given work permits in the marine shipyard sector, but only Malaysians and North Asians can be given work permits for the services sector), to the privileging of Chinese students in Special Assistance Plan schools that get more government support—so any claim of ignorance from a Singaporean is pretty much wilful blindness at this point.” One might argue with Raeesah’s characterisation of it being “merciless”, but it’s a fact that minority races are disproportionately represented in Singapore’s prison population, and a study suggests that “uneven distribution of ethnic capital restricts the ability of the Indians and Malays and enables the Chinese to achieve acceptance into the mainstream.”

And because it’s a system, racism is something that goes beyond individual behaviour and choices. For example, as a Chinese person, I might not want to be treated better, or have better opportunities, than my minority friends. But it doesn’t matter what I want: because I’m Chinese, and because other people in Singapore see that I’m Chinese, I’ll automatically have some advantage over non-Chinese friends: I’ll face less discrimination when I’m looking to buy or rent property (including HDB flats that are affected by ethnic quotas), I don’t have to worry about being excluded from job ads that demand bilingual speakers, where “bilingual” is really code for “Chinese people who can speak English and Mandarin”, and society is generally willing to acknowledge my personhood and not see me as a stand-in for, or representative of, my entire race. I don’t have to actively participate and be racist to benefit from this system simply because I had the good luck to be born under the “right” letter in Singapore’s CMIO society.

Some will undoubtedly ask, “Can’t minorities be or say things that are racist too?” Sure, people who are minorities in their society can definitely be prejudiced and say prejudiced and hurtful things to those in the majority. But the impact is different: when a Malay or Indian Singaporean employs a race-based slur against me, a Chinese person, it might hurt my feelings, but it doesn’t connect to an entire structure of discrimination that affects my daily life. I might feel sad or angry, but it’s unlikely to affect how employers, the rental market, and government policies treat me.

But when racist statements and slurs are made against minorities, it feeds into an entrenched mindset that justifies and props up the negative stereotypes and assumptions that allow us to continue with discriminatory behaviour. And because minorities aren’t able to simply “step out” of a society that discriminates against them, the racist comments, slurs, and micro-aggressions cause additional hurt on top of the unequal treatment they face.

So yes, people from minority races can be prejudiced, and can say things that are racist towards a member of the majority race, but what that member of the majority experiences isn’t “reverse racism”, because we aren’t experiencing an entire system of oppression. We’re experiencing interpersonal shittiness.

*Of course, a proper nuanced discussion will have to take into account intersectionality, where other factors like class and gender and nationality come into play — but I’ve chosen to only address the myth of reverse racism in the most basic way here.

How can we talk about race, religion, and injustice in Singapore?

Conversations about race and religion are generally very stunted in Singapore, because they’ve been beyond the “out-of-bounds markers” (OB markers) for such a long time that Singaporeans know they’re very sensitive and will tend to stay away from the boundaries. Laws like the Sedition Act and Section 298A of the Penal Code add to this by causing a chilling effect.

Over time, we’ve grown unfamiliar and uncomfortable with conflict. Coupled with a tendency to appeal to authority, we now have a situation where people choose to file police reports rather than engage in debate, thus further propping up the paternalism of the political elite that assumes Singaporeans need to be managed and controlled. (And then more paternalism further entrenches a mindset where Singaporeans expect the authorities to take care of everything, and the cycle continues down the authoritarian rabbit hole…)

As Cherian George points out, such laws can also be weaponised for political gain. They open up the avenues for people to go trawling through social media to find something to claim offence against.

Until we face up to and get over this fragility, it’ll continue to be extremely difficult for us to have meaningful conversations that will begin the process of dismantling systemic racism in Singapore. And we shouldn’t mistake this lack of conflict for true harmony or a lack of enmity between racial or religious groups; it just means that these issues are more likely stewing below the surface rather than openly addressed and dealt with.

Investigating Raeesah for saying that there’s differentiated treatment along class, racial, and religious lines doesn’t mean that there’s no differentiated treatment; it just means that people are warned not to speak up, and dissatisfaction and a sense of injustice can continue to fester beneath the veneer of “racial harmony”.

We should ask ourselves if this state of affairs is good for our society in the long-run.

If you’d like to read about what it’s like to be invited to lim kopi with the police, I’ve written about it here, based on my own experience and observations from seeing other members of civil society called in for questioning.

Thank you for reading! If you’d like to support my work, please consider becoming a Milo Peng Funder by getting a paid subscription, or buying one for a friend:

Subscribe nowGive a gift subscription

You can also help spread the word by sharing this issue!