Check out We, The Citizens’ spreadsheet compilation of party manifestos for this election. If you’re looking for an explainer on the election itself, New Naratif has a comic explainer for you.

I’m preparing for an opposition wipe-out.

No, that’s not a prediction. It’s just that, after GE2015, then Trump, then Brexit, I’ve decided that bracing for the worst-case scenario means I should only get good news from here on in. Let’s see if this works. I’ll let you know on 11 July.

Election campaigning has officially begun. Over the next week we’re going to be seeing posters and flags and hearing from the candidates — here’s the schedule for the party political and constituency political broadcasts. If you need a list of who’s going where, here’s a handy guide from Yahoo! Singapore.

The Workers’ Party has been worried for some time that the People’s Action Party will win big and we’ll end up with no opposition presence in the House at all. “Let us never forget that we only have a toe-hold in parliament... The risk of a wipe-out with no elected opposition represented by the Workers’ Party is a real one,” WP leader Pritam Singh said in January.

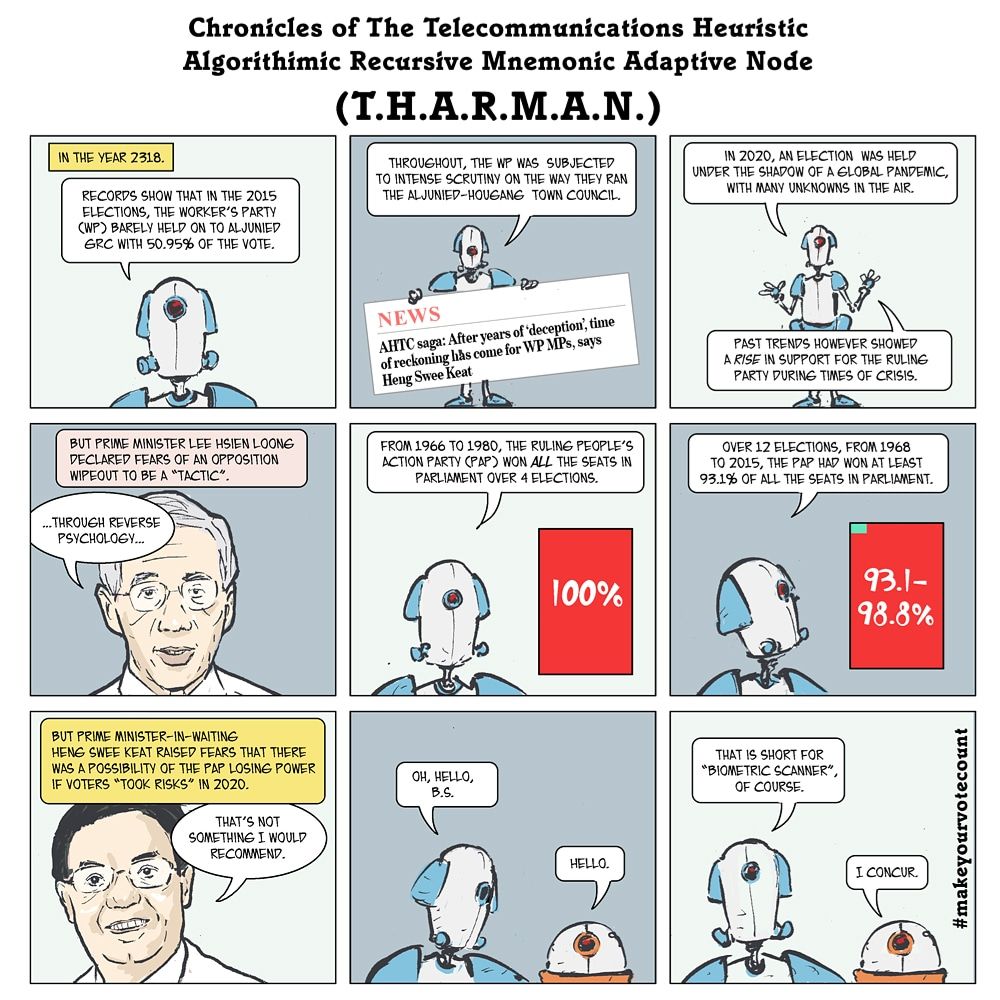

Lee Hsien Loong has rubbished this, saying that it’s just an attempt at reverse psychology and that an opposition wipe-out isn’t a “realistic outcome”. His potential successor Heng Swee Keat has gone further to suggest that it’s possible that the People’s Action Party might get voted out if everyone decides to “take a risk” and vote for the opposition.

But so what if no opposition candidates get elected? Indranee Rajah doesn’t think it’s a big deal, because she argues that there’ll be 12 Non-Constituency Members of Parliament anyway.

The Uniquely Singapore Calculation

I think most readers of this newsletter are Singaporeans who’d be familiar with this already, but there are some non-Singaporeans among you too, so I don’t want to skip anything.

When looking at the chatter about elections and voting, the first thing to understand about Singapore is that it’s not like other democracies where it’s about choosing which party to put in power. We might have inherited a Westminster system from the British, but Singapore’s politics is very far from being akin to picking between a Tory government, a Labour government, or even a hung parliament.

For the most part, Singaporeans want a PAP government. That’s why the PAP’s worst performance was still about 60% of the vote — a dream scenario for any party in more competitive, mature democracies.

But Singaporeans are also talking about the need for more opposition voices in Parliament; there’s an awareness that such overwhelming dominance in the House isn’t the best situation to be in. People want more opposition members to get into Parliament so they can ask questions, push for debate, and keep the leaders accountable (or, at least, more accountable).

This creates a need to figure out a balance, where sufficient numbers of voters elect opposition candidates, while not having too many people vote opposition to the point where we have a “freak election”, where the PAP fails to win a majority of the seats and therefore can’t form government. And because there aren’t any voter opinion polls, it’s hard for the electorate to really know which way things are going.

So. What does Indranee mean about the NCMPs?

Non-Constituency Members of Parliament aren’t elected by the public, but are the “best losers” from opposition parties. If fewer than 12 opposition candidates are elected in an election, then these “best losers” will be brought in to make up that number. In this way, there will always be at least 12 members of opposition parties in Parliament, even if they aren’t all elected MPs.

This NCMP scheme was first introduced in 1984, after Singaporeans voted in opposition politician J.B. Jeyaretnam in the Anson by-election in 1981, breaking the 100% grip the PAP had on Parliament for 16 years.

Indranee Rajah isn’t the first, and won’t be the last, PAP politician to suggest that Singaporeans eager for and opposition presence in Parliament won’t have to vote for them. To understand a little more about the motivations and reasoning behind the introduction of this scheme in the 1980s, I dug into the Hansard to look at what then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew said (emphasis below mine):

Why should we deliberately ensure that Parliament, henceforth, should have at least a few Opposition Members? There are several reasons. First, from our experience, since December 1981 when the Member for Anson entered this Chamber, we discovered that there are considerable benefits for younger Ministers and MPs. They have not faced the fearsome foes of the 1950s and 60s. Initially, they were awkward in tackling the Opposition Member. But they soon sharpened their debating skills and they have learned to put down the inanities of the Member for Anson.

(J.B. Jeyaretnam: “That is what you think.”)

Secondly, and much more important, Opposition MPs will educate a younger generation of voters who, not having experienced the conflicts in this House in the 1950s and 60s, harbour myths about the role of an Opposition. Although they may be disillusioned by the performance of the Member for Anson, some hope that other Opposition candidates can be more credible and effective. Well, let there be others. The people will learn the limits of what a constitutional Opposition can do.

Thirdly, some non-PAP MPs will ensure that every suspicion, every rumour of misconduct, will be reported to the non-PAP MPs, at least anonymously. We all know that. These MPs, unlike PAP MPs, will give vent to any allegation of misfeasance or corruption or nepotism, whereas PAP MPs know that they should only take up the matter after enquiries show that allegations have some shadow of truth. This approach of Opposition Members will dispel suspicions of cover-ups of alleged wrongdoings.

In brief, within eight months after the Member for Anson entered this Chamber, my senior colleagues and I came to the conclusion that the new situation, contrary to our expectations, was better for Singapore, better both for the Government and for the people. It is no longer in the interest of Singapore for the 1980s that the old guards should exert their dominance to exclude the Opposition in a general election so that distraction from our vital goals is minimised. We did this for the 1960s and 70s in order that the people could concentrate on the urgent tasks of survival. The position has changed, not just the challenges confronting us but also the nature of the electorate. Over 60% of today's voters are aged 40 and below. They were teenagers or toddlers when the struggles were enacted in the 1950s and 60s. They have no idea how destructive opposition can be. They feel that they are missing something. They want to experience some of the excitement of political combat.

In a nutshell, LKY and his colleagues felt that voters in the 1980s wanted opposition in Parliament. But LKY also thought that the young Singaporeans of that period didn’t understand the reality of what they wanted:

This younger generation does not know what is, or should be, an Opposition's role. Some believe that a government can be made to change its policies by vociferous protests or nagging and repetitious arguments. Others believe that they, as voters, will do boner with an Opposition pressing and coercing more benefits out of a hard-fisted government.

So the idea was that the NCMP scheme would “teach” Singaporeans that there was no need for official opposition, while PAP MPs could use NCMPs as sparring partners to sharpen their skills.

Opposition politicians have criticised the NCMP scheme — even as some of them have partaken in it. In 1984, J.B. Jeyaretnam characterised the constitutional amendment bill that would introduce this scheme as “a fraud on the electorate”.

“If the Prime Minister is genuine in his desire to see Opposition Members in Parliament and therefore bring about parliamentary democracy in Singapore, then may I tell him that there are other ways of doing this, far better ways than this sham Bill,” he said.

When the scheme was first introduced, it only allowed for three NCMPs, who would have limited powers. The number of NCMPs were increased in the intervening years, and in 2016, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that NCMPs would be given full voting powers. But the criticism remains: how democratic is the NCMP scheme? And if it’s being wielded as a tool to tell Singaporeans not to vote for the opposition, does it actually hinder the development and maturity of democracy in this country?

*For those who want further reading, check out “Constitutional-Electoral Reforms and Politics in Singapore” by Hussin Mutalib.

How realistic is an opposition wipe-out?

(Comic by Sonny Liew)

Let’s just get this out: the idea that enough Singaporeans will up and vote opposition to the point that the PAP can’t even get the 47 seats (out of 93) needed to form a majority is extremely unlikely. Before Parliament was dissolved, the PAP had 82 seats — they would have to lose 36 seats to lose the majority.

As WP’s Leon Perera points out, the PAP has also fielded senior PAP members in most of the constituencies, presenting voters with the risk of kicking out a minister should lean in favour of the opposition. This isn’t a new strategy: having GRC teams led by an anchor minister has generally worked well for the PAP. The only time it worked against them was in 2011, when WP won Aljunied GRC and George Yeo (the former foreign minister) and Lim Hwee Hua (the former minister in the Prime Minister’s Office) lost their seats.

The scenario of the PAP winning big and us ending up with no elected opposition in Parliament is far more likely. In 2015, WP only just won Aljunied GRC with 51% of the vote, and Hougang SMC with 58%. It won’t take that much of swing for them to lose their seats.

There’s already speculation that a PAP sweep will be the case, since voters might be even more risk-averse than usual given the extraordinary times that we’re in given COVID-19 and the recession. If the “flight to safety” mindset is prevalent within the electorate — and the PAP certainly keeps emphasising what challenging times it is and how they need a “strong mandate” to lead Singapore in weathering the storm — it’s possible that GE2020 will turn out very well for the ruling party.

Oh well… let’s see how things play out over the next 10 days. Despite my decision to embrace strategic pessimism, I’m actually a bit excited. And you can rest assured that there is a Plan. A together plan. Especially for those of you in East Coast.

If you enjoyed this issue, please considering becoming a Milo Peng Funder so I can keep devoting more time to writing this newsletter and covering Singapore independently!

You can also help me get the word out by sharing this issue/newsletter: