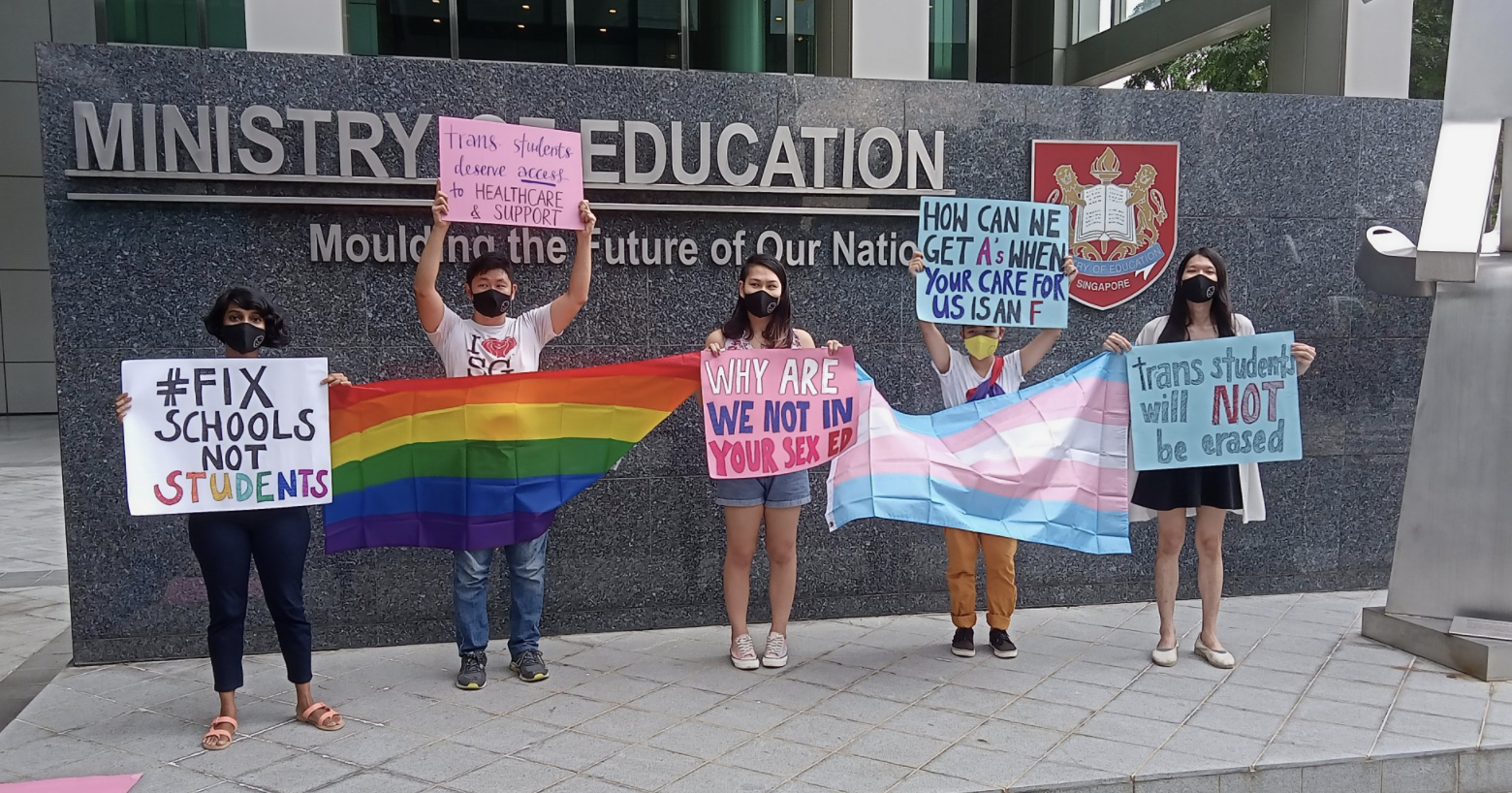

Yesterday, five Singaporeans — some students, some not — staged a very short-lived protest outside the Ministry of Education headquarters, against institutionalised transphobia in schools. They stood next to the MOE sign with a Pride flag, a Trans Pride flag, and placards.

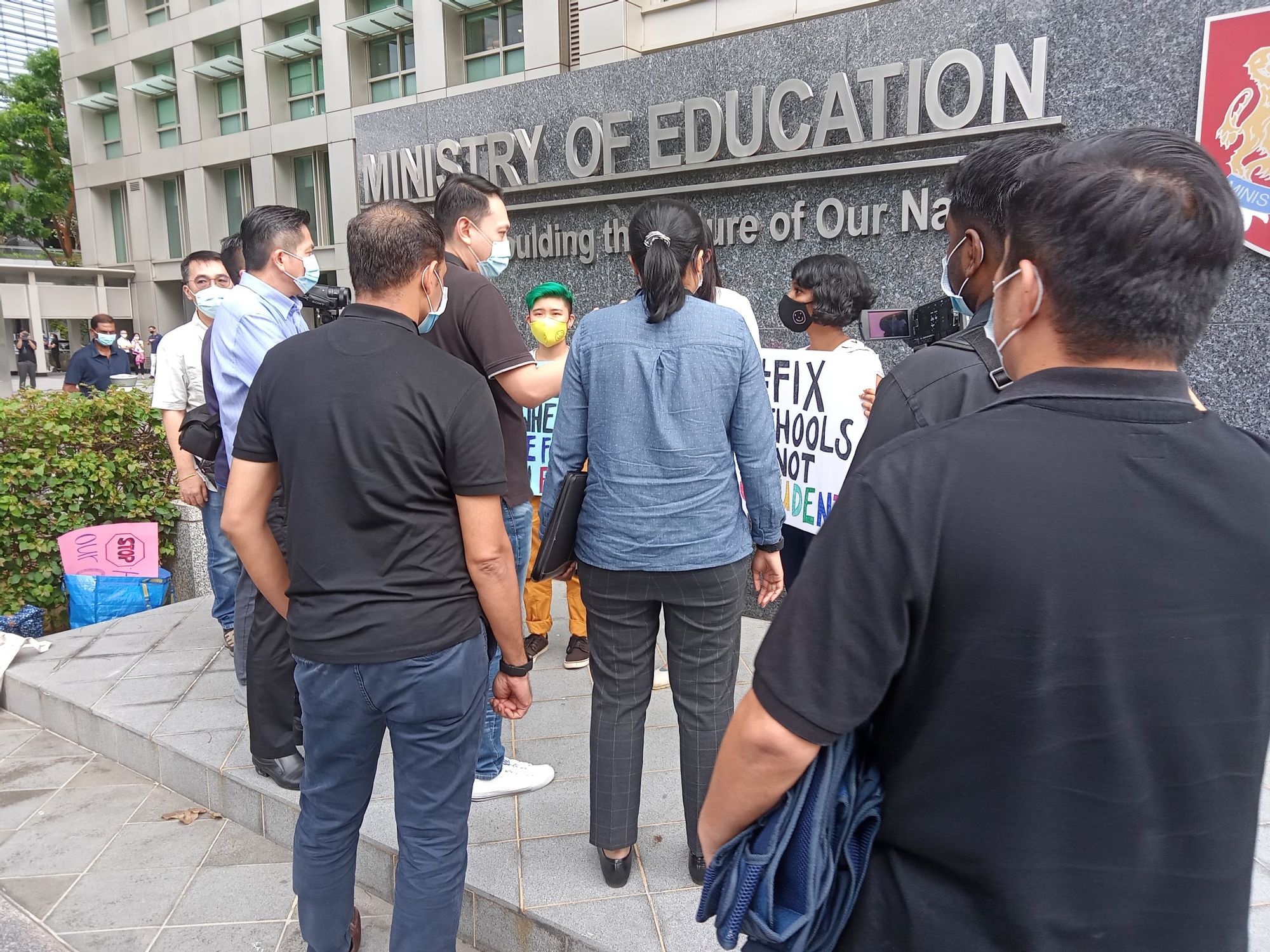

I suspect that the police knew they were coming; even as they were setting up, I noticed a guy (who might have been plainclothes police) filming/photographing them. The protesters were approached by security within minutes. Two of the protesters then decided to leave. Judging from the speed with which a bunch of plainclothes police appeared and surrounded the remaining three protesters, they couldn’t have come from very far.

There was some back-and-forth between the officers and the protesters. I didn’t catch the whole conversation — there were so many cops, outnumbering the protesters and surrounding them — but officers tried to convince them to leave. The protesters were polite, but firm; they discussed the situation among themselves and chose to stay. I heard one officer say that there were “other avenues” for them to raise their issues.

"There have not been other successful avenues,” was the response. The protesters pointed out that, over the years, LGBT groups have put out multiple statements about discrimination and prejudice. But so little has changed.

The protesters were issued “move on” orders, but decided to stay on. Eventually, they were placed under arrest and put into a police van.

It all happened so quickly: from the taking out of the placards in the beginning to the arrest at the end, it’d all only taken about half an hour. The amount of police presence ended up creating a larger crowd than would ever have been managed by three protesters with signs.

The three arrested protesters were eventually bailed out later at night by friends and supporters. The other two protesters who’d left — and therefore not been arrested — were called in for questioning; one has already spoken to the police, and the other is going in later this afternoon. We’ll have to wait and see what happens next; they’re currently being investigated under the Public Order Act.

Ng Yi-sheng, one of the protesters who wasn’t arrested, has written about his decision to participate:

Though MOE boasts of "Moulding the Future of Our Nation", it's been failing trans SGans for generations. Friends tell me it's routine for trans girls to drop out early because of bullying & become sex workers cos they have few other options. (Sex work is valid work, but it should be chosen freely.) #fixschoolsnotstudents isn't just about Ashlee: we need to do better by *all* trans youth in the system.

[…] & it's not just about trans youth! Kids of all genders & sexual orientations—including me, including some of my cishet friends—have suffered bullying & shaming in school because of v rigid ideas of "masculinity" & "femininity". Better acceptance of transgender folks *also* helps cisgender folks.

[…] Regarding the legality of this action. Public protests w/o a permit are illegal in SG. But so is jaywalking. Wouldn't you jaywalk to help a child?

[…] As you may have noticed, I'm the only cisgender man among the 5 protesters. At 40, I'm also the oldest among them by far. But this wasn't my idea: when I was invited to join, I felt the same kind of fears as anyone would, & only agreed when I realised I wouldn't be able to live with myself if I refused. I'm economically privileged & already have an established reputation that isn't going to be greatly damaged by this. If trans youth want me to stand up as an ally—if they're willing to accommodate my fears enough to let me leave as soon as trouble arrives—then how can I say no?

Although public case has recently been drawn to this issue of transphobia in Singaporean schools by Ashlee, an 18-year-old transgender student who says her school, Millennia Institute, continues to force her to cut her hair and don the boys’ uniform (I covered this in a previous issue), the issue of LGBT discrimination in schools is not new. The protesters' statement draws attention to this:

Students themselves, human rights and civil society groups, as well as educators, counsellors and other professionals working with young people, have raised concerns about discriminatory and intrusive practices by schools, which hurt both LGBTQ+ students, as well as heterosexual and cisgender students, by undermining privacy, bodily autonomy and well-being. These practices include (but are not limited to):

• Checking and controlling whether students’ clothes, hair and bodies match gender norms imposed by schools, including through intrusive clothing checks (e.g. examining underclothes)

• Prohibiting and policing students’ dating and intimate relationships, including punishing or shaming students for relationships

• School counselling which treats LGBTQ+ identities as problems to be done away with (e.g. conversion therapy) rather than affirming students’ autonomy and identities

• Disrespecting students’ confidentiality and outing them as LGBTQ+ to family members or other persons without their consent

• Physically excluding students from school based on whether they look like a gender the school imposes upon them. Home-Based Learning (HBL) could be offered, but not imposed, for all students whose circumstances might make HBL a preferred option for a period.

• Refusing to use gender pronouns requested by students

• Censoring mention and open discussion of LGBTQ+ experiences and identities, including by disciplining or policing educators

• Continuing to discuss LGBTQ+ identities mainly in the context of informing students during sex-ed that Section 377A deems homosexual conduct illegal and opposed to societal norms, and failing to provide LGBTQ-inclusive information on sexual and reproductive health and well-being.

The following is a guest contribution to the newsletter written by Alexander. Alexander (he/him/his) is a youth worker with Oogachaga, a community-based, non-profit professional organisation working with LGBTQ+ individuals, couples, and families.

I’d asked Alexander to write this before the protest, and am so glad this issue has been made richer by his contribution! 🙏🏼

In 2018, then-Minister for Education Ong Ye Kung said that there’s no discrimination against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community “at work, housing (and) education” in Singapore.

The sheer confidence with which he made his proclamation made me want to believe him, despite knowing full well that this wasn’t, and still isn’t, the case.

In a recent Reddit post, 18-year-old transgender student Ashlee (not her real name) shared being denied the right to proceed with hormone replacement therapy while continuing her education in junior college. This happened despite her producing a psychiatrist’s letter confirming her diagnosis of gender dysphoria — a prerequisite for transgender people in Singapore to commence gender-affirming medical treatment.

[Note: Hormone replacement therapy, or HRT, is one of the treatments recommended for individuals who are diagnosed with gender dysphoria — the psychological discomfort experienced by a person whose gender identity does not match their assigned sex at birth.]

Although Ashlee’s parents have consented and are supportive of her transition, the school insisted that she’d have to keep her hair short, in accordance with the school’s rules for boys. She was also told that she had to keep wearing the boys’ uniform, and to ensure that her hormone replacement therapy wouldn’t result in physical changes that would prevent her from fitting into it.

Not complying with these conditions would mean expulsion from school.

While the Ministry of Education (MOE) has disputed this account, Ashlee’s case isn’t an isolated one. As a gay transgender man, I’ve personally experienced and heard of other instances of discrimination towards LGBTQ+ students in the formal education system.

Unlike Ashlee, I never went to junior college. My secondary school years were extremely unpleasant (and I also failed Combined Science), so that’s when I decided the polytechnic route was for me, and my time in a school uniform ended. But during that time, I, like Ashlee, had to contend with rigid school rules, ill-informed teachers and school staff, and downright uncomfortable everyday school experiences.

My classmates and I were made to sign abstinence cards after a very passionately delivered sexuality education class. At the tender age of 13, we vowed not to have sex until we were in a “faithful”, monogamous marriage with someone of the opposite sex. We were only taught about boy/girl relationships. A good friend of mine who was seen holding hands with her younger sister on school grounds was pulled aside by a teacher, and told in hushed tones that “this is not the correct way to behave”. We would overhear teachers and staff mocking their colleagues and gossiping about students and who they thought was a “butch”, or “fairy”, or “pondan”, or “bapok”, or “tranny”.

I was made fun of for my rapidly developing body, a body I tried so desperately to hide under an oversized school blouse and a slouch that I’m still trying to get rid of years later. After I confided in one of my favourite teachers about how I felt, she brushed it aside, telling me to get my hormone levels checked and “sorted out” and I’d be all right.

There are no known policies that protect LGBTQ+ students against discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity, nor is there a curriculum that teaches children about, and affirms, diverse identities. Adolescence is in itself a trying time for many; for young LGBTQ+ people, especially those who are transgender, feeling the need to hide their journey of self-discovery and identity, so as to avoid being bullied, is exhausting and demoralising.

What upsets me the most hearing about Ashlee’s case is being reminded, yet again, that Singapore hasn’t only failed in tackling discrimination against a marginalised community; we’ve also denied a young person their right to education in a safe, affirming environment.

Ashlee has other options to continue her post-secondary education; she’s said that she’s considering leaving junior college and going to a polytechnic instead. But this isn’t a choice that she should have to make; she has every right to pursue her chosen path. Nobody should have to choose between their education and their freedom to be their authentic selves without fear.

Unfortunately, even after hanging up our school uniforms for good, there are other hoops for us to jump through. Transgender folks experience various instances of discrimination well beyond our school years. The absence of legal protection means that transphobic employers can reject our applications or fire us for being transgender. Lengthy government job application forms require male applicants to declare their National Service — an experience that transgender women often find awkward and unpleasant to share, and one that transgender men do not have.

Marriage — and by extension applying for public housing and adopting children — is often off the cards for many of us who aren’t in straight relationships, or those of us who haven’t changed our sex markers on our NRICs. That is, if we’re lucky enough to be able to change our sex markers at all: ICA now requires transgender people to undergo invasive genital reconstruction surgeries, and be examined by a specialist before being allowed to make the change on our documents. Even though gender affirming surgeries have been proven to have long-term benefits on transgender individuals’ mental health, it isn’t covered by insurance companies in Singapore, rendering a happy, healthy life inaccessible to many, particularly younger transgender people.

I turn 26 this year. It’ll be ten years since I’ve left the formal education system. It frustrates me greatly knowing that, although my country places great emphasis on the quality of formal education, it ignores young LGBTQ+ students fighting to live their lives authentically in their schools — places that young people should be able to consider safe harbour. Do we really believe in ensuring each child has the opportunity to an education when we insist on policing who they are allowed to be as individuals?

This is a reminder of the desperate need for MOE, and the rest of the government, to re-evaluate their priorities. Perhaps then, future Ministers for Education can stand in Parliament and declare that there is no discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community at work, housing, and education… and actually mean it.

Feel free to share this post!

Oogachaga does extremely valuable work providing LGBT-friendly counselling services. Click the button below to donate to them: