It’s time for the weekly wrap again, but I’m not writing one this week. I know it’s been newsy, what with all the coverage of the Committee of Privileges debate in Parliament, as well as the Budget, and I’ll be circling back to the COP kerfuffle later, but today I’d like to focus on something else that hasn’t been getting much attention in the local press.

Recently, whenever I speak to family members of men on death row in Changi Prison, they tell me of fears that executions might be restarted with a vengeance. There are over 50 men on death row (much less is known about the situation at the women’s prison), and around 20 of them have exhausted the legal process and even their clemency appeals, leaving them in danger of imminent execution. It’s become clear that the number of people Singapore condemns to the gallows each year is higher than the number that it’s been executing. For years, I have heard whispers of a backlog building up. People are now terrified that the prison will pick up the pace of hangings because death row is getting, as families relay to me, “too full”.

This situation is not widely known. The death penalty is not an issue that comes up in the local media much. Even when so much happened this week, coverage has been sparse, confined only to court decisions and official action.

Respite for Roslan and Pausi

In last week's wrap, I wrote about the families of Roslan Bin Bakar and Pausi Bin Jefridin receiving execution notices informing them that the prison intended to hang the two men on 16 February. A frantic week has passed, with multiple applications filed to the court and unbelievably tight timelines.

On Wednesday, the High Court heard an application at 9:30am. At 12:38pm, human rights lawyer M Ravi posted on his Facebook page that the application had been dismissed, and the lawyers directed to file their appeal by 1:45pm. (This required an undertaking of $20,000 in security, thus prompting a desperate rush of fundraising.) Incredibly, the appeal was then fixed for 3:15pm that very afternoon. It was eventually dismissed that evening.

Thursday brought more drama. A final application had been filed the evening before, and a hearing had been fixed for 9:30am. But Violet Netto, the 78-year-old lawyer arguing the case, was experiencing side effects from her Covid-19 booster shot and couldn’t make it to court. According to reports, the court demanded that she show up to argue the case anyway. She was too sick to do so. After a few hours of anxious waiting for updates, I heard from Roslan’s sister that the prison had given her a letter informing her that President Halimah Yacob had granted Roslan a respite from execution. I was later able to confirm that Pausi’s family received a similar letter.

Unlike a pardon, a respite is only temporary. It’s likely that this respite order will remain in place until Roslan and Pausi’s final application is heard by the courts. It’s by no means a full victory, but it does mean that they are safe until the next court hearing.

Hearing this news felt like being able to breathe properly for the first time in days.

But there’s more

With this temporary reprieve, Roslan and Pausi join the ranks of Pannir Selvam Pranthaman, Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin, Moad Fadzir Bin Mustaffa and Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam. All of them had been scheduled for hanging, only to be saved at a late stage by stays of execution or respite orders while legal matters were before the court. (Worryingly, Pannir, Syed and Fadzir no longer have pending court cases any more, which means they’re once again in danger of imminent execution.)

It would already be bad enough if this was the end of it. But on Wednesday I received more bad news: the prison has scheduled Rosman bin Abdullah’s execution for 23 February (Wednesday).

Like all the others mentioned here, Rosman had been convicted of drug trafficking. Like Roslan, Pausi and Nagen, he’s been on death row for over a decade. Like them, lawyers had sought life imprisonment instead of a death sentence by making arguments about abnormality of mind at the time of offence. Section 33B of the Misuse of Drugs Act says that the courts have to impose a life sentence instead of death if a drug courier was suffering from an abnormality of mind that substantively impaired their mental responsibility for the act.

Dr Munidasa Winslow, a psychiatrist, wrote a report saying that Rosman had met the diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), stimulant use disorder and sedative use disorder.

“Mr Rosman’s long-term polysubstance use history from a very young age is likely due to a combination of factors including underlying low IQ and learning difficulties exacerbated by undiagnosed and untreated ADHD, long-term physical abuse and neglect from early childhood, and the resulting subsequent stunted emotional and cognitive development,” Dr Winslow wrote. However, the Court of Appeal found that Dr Winslow’s conclusions were too general and vague, and did not satisfy the clause within the Misuse of Drugs Act relating to abnormality of mind at the time of offence. In any case, they said, the point was moot because Rosman had needed to demonstrate both abnormality of mind that diminished his responsibility for the offence and that he had merely been a courier. Since the court agreed with the prosecution that Rosman’s role had been more than that of a courier, it wasn’t actually relevant what his mental condition was.

What is all for?

I’ve written over and over and over and over again that there is no proof that Singapore’s death penalty regime actually deters the drug trade. Furthermore, capital punishment and other harsh anti-drug policies don’t help people who struggle with drug dependency or problematic drug use; it just creates more victims and more trauma out of people who are already marginalised or vulnerable.

Ethnic minorities are disproportionately represented on death row in Singapore. Between 2010–2021, out of the 77 people sentenced to death (and had their appeals dismissed), 50 of them were Malay. Many of the prisoners whose cases I have come across have also struggled with poverty, access to education and opportunities, histories of abuse or neglect, drug dependency, or intellectual or psychosocial disabilities.

As I told VICE World News this past week: “When we find that a system is repeatedly and disproportionately affecting marginalised communities and other vulnerable people, we should really be asking if such a system can really be described as ‘justice’.”

The Big Boys

One popular depiction of a drug trafficker deserving of capital punishment is the greedy peddler of death, tempting people into wrecked lifetimes of addiction for the sake of turning a hefty profit. I’ve not yet come across a case on death row that fit this description. As far as I’ve seen, there are no power- and money-hungry drug lords on death row.

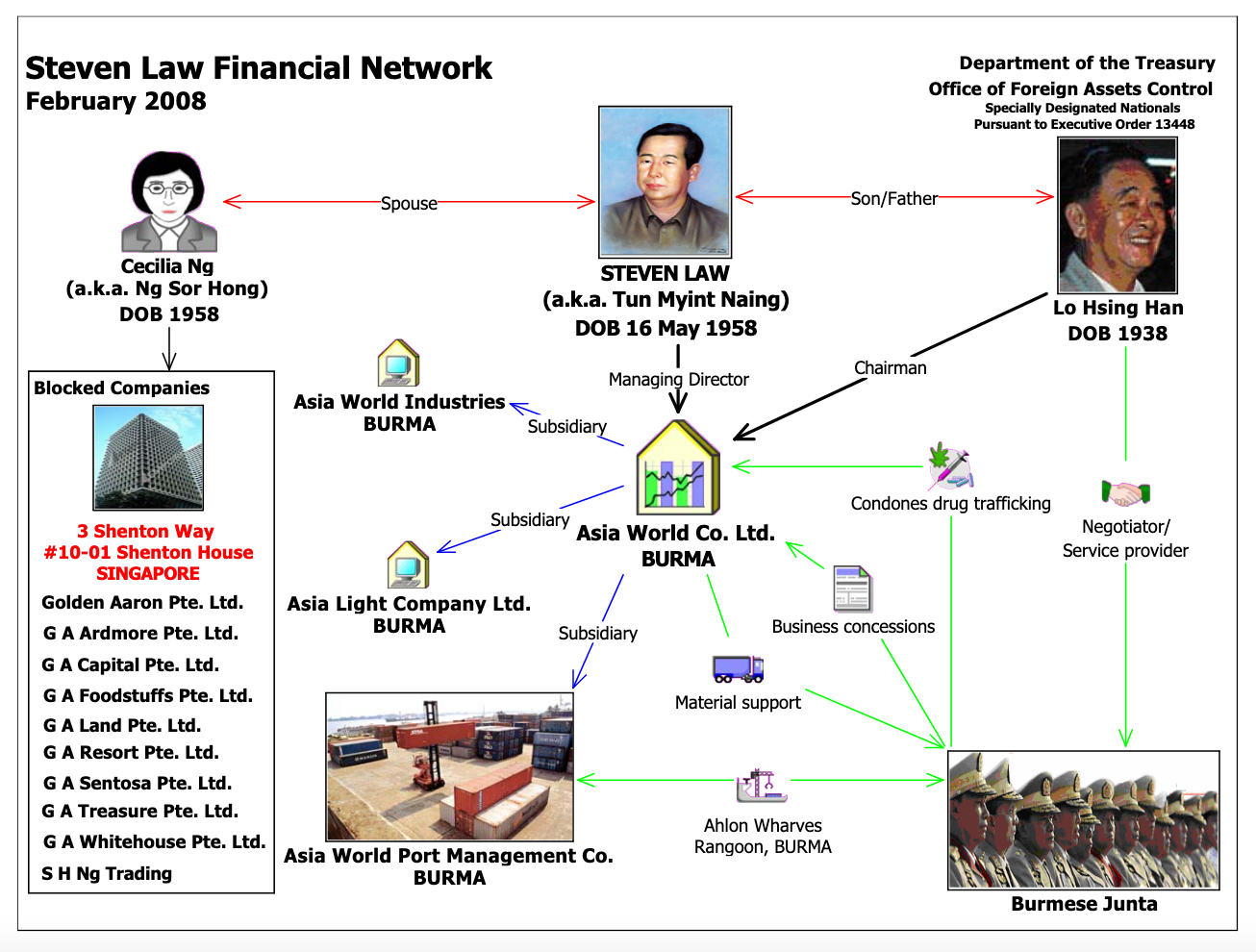

That doesn’t mean big players haven't set foot in Singapore. Back in February 2008, the United States Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added three people to their Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons (SDN) list: Burmese citizen Lo Hsing Han, his son Steven Law and his Singaporean daughter-in-law Cecilia Law. The US Treasury department described Lo Hsing Han and Steven Law as “key financial operatives of the Burmese regime” and noted that they had “a history of involvement in illicit activities.”

“Lo Hsing Han, known as the ‘Godfather of Heroin’, has been one of the world's key heroin traffickers dating back to the early 1970s. Steven Law joined his father's drug empire in the 1990s and has since become one of the wealthiest individuals in Burma,” OFAC claimed in its press statement. Also designated was the family’s conglomerate, Asia World, and 10 companies in Singapore owned by Law’s wife Cecilia.

Although Lo Hsing Han died in 2013 — and, as far as I could tell by searching OFAC’s database, Steven and Cecilia Law are no longer on the SDN list — the connection between this family, the Burmese junta and the Singapore government was known and documented. In 2005, the Australian newspaper The Age published this article in which it highlighted criticism of Singapore’s hypocritical anti-drug stance, pointing out Singapore’s investment and business ties with the Burmese state despite its reputation as one of the world’s biggest supplier of heroin. Lo Hsing Han and Steven Law were explicitly named as key players in this relationship. And that wasn’t even the first time these ties had been reported.

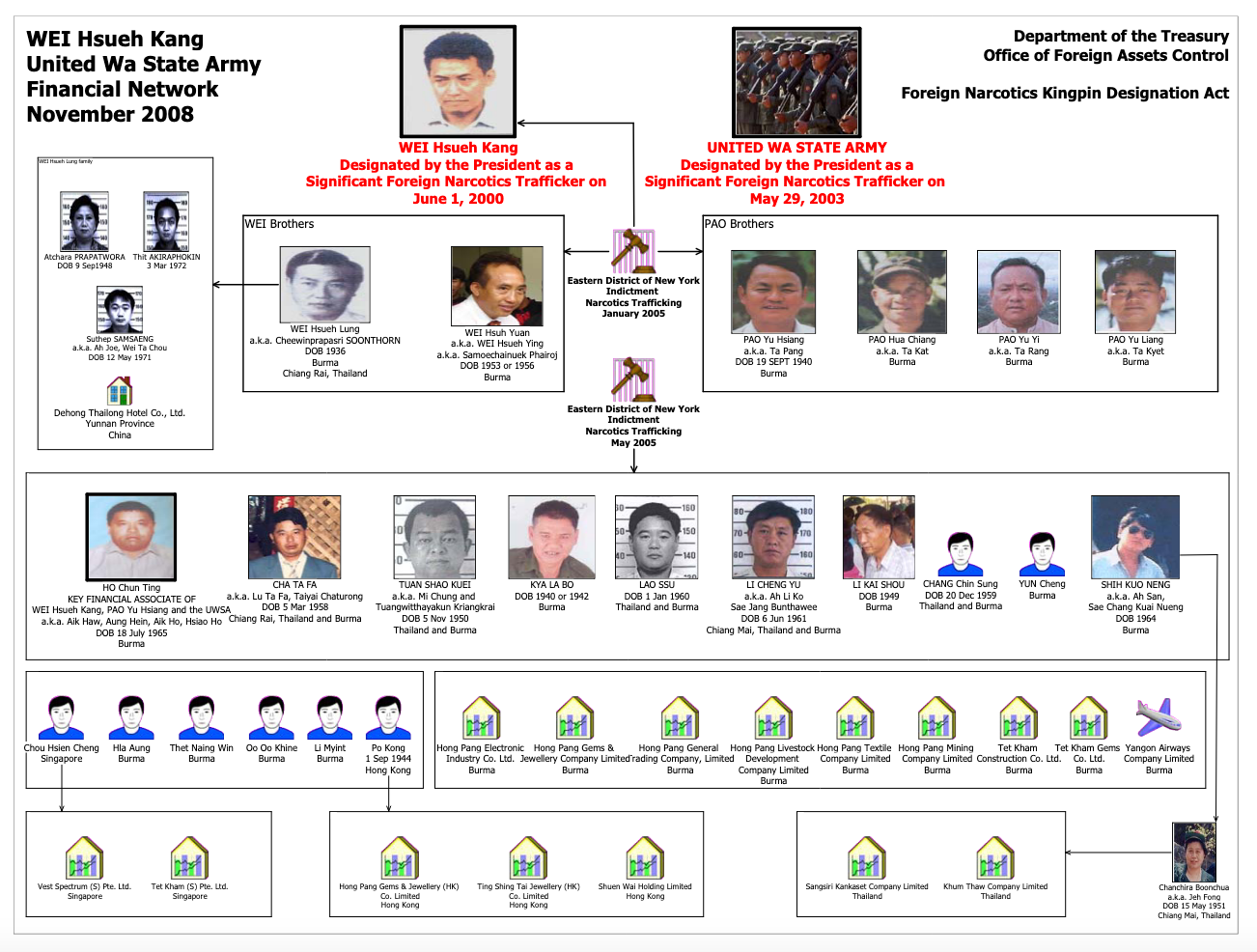

In November 2008, OFAC made another announcement: they named 26 individuals and 17 companies as Specially Designated Narcotics Traffickers under the US’ Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (also known as the Kingpin Act). These individuals and entities were linked to the drug trafficker Wei Hsueh Kang and the United Wa State Army, described by OFAC’s deputy director Barbara C. Hammerle as “the largest and most powerful drug trafficking organization in Southeast Asia and is a major producer and exporter of synthetic drugs, including methamphetamine.”

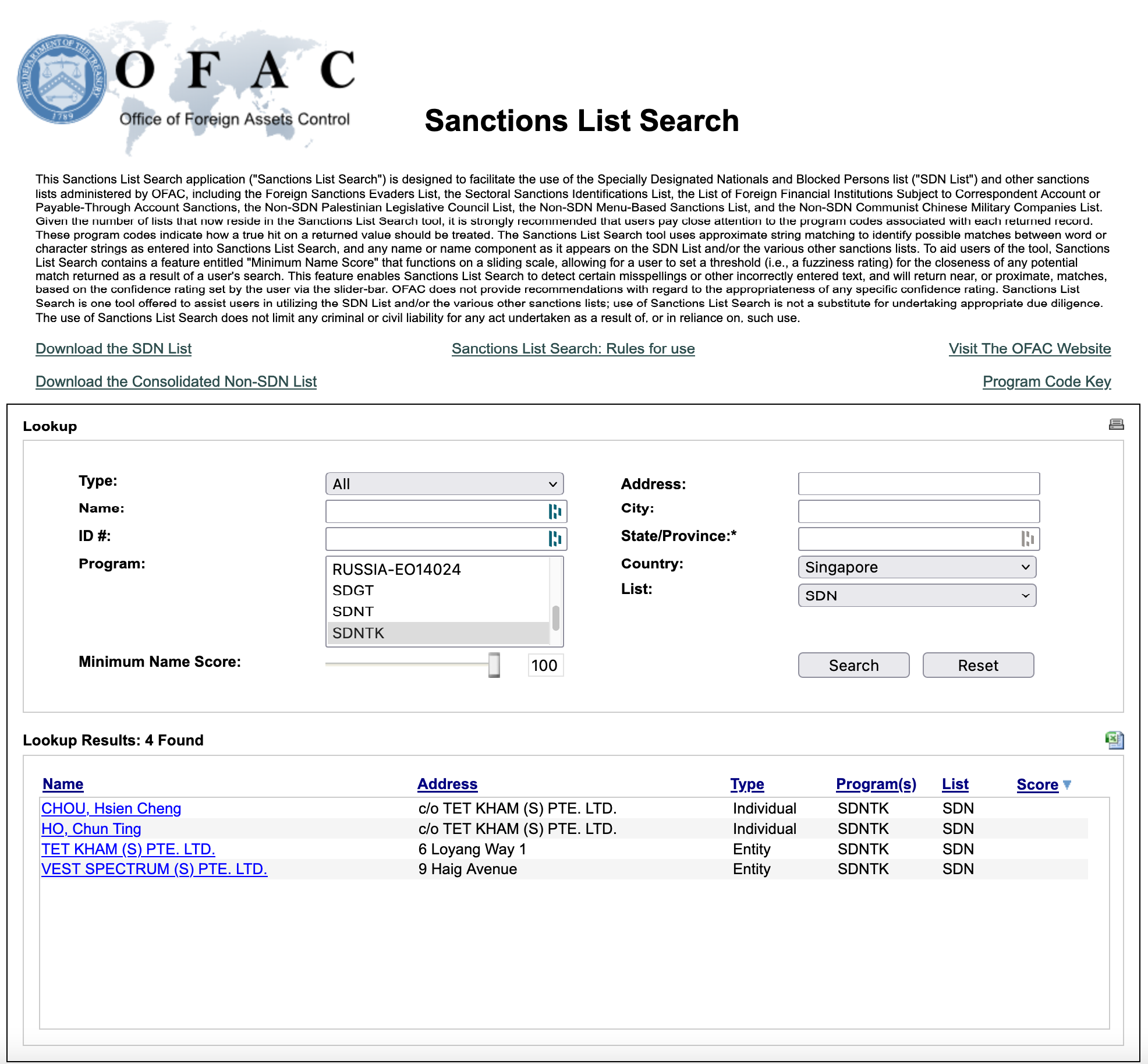

A man named Chou Hsien Cheng was on the list. When I went further down the hyperlink rabbit hole, I discovered that Chou is Singaporean and linked to the companies Tet Kham (S) Pte. Ltd. and Vest Spectrum (S) Pte. Ltd., both of which were also on the designation list. Both those companies were registered in Singapore. According to a search of the SDN database I did yesterday, Chou and the two companies are still designated.

When I searched Singapore's Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) Register, I found that both Tet Kham and Vest Spectrum have been struck off. I tried Googling both company names to see if I could find out more, but didn't find anything particularly significant. I also haven’t been able to find out what, if anything, has happened to Chou Hsien Cheng (searching both this name and his other name Chew Kheng Siang). It sure doesn't seem like he's on death row.

To be clear: I’m not saying that he should be put to death, since I don’t think the death penalty should exist at all, but our “zero tolerance” drug policies don’t make sense if we’re only putting poor ethnic minorities, carrying relatively modest amounts of drugs, to death.

What do we do now?

Singapore has spent decades putting people to death for drug offences. It's a cruel policy that's full of contradictions. We claim to be winning this war on drugs, yet there seems to be no end of people to arrest, convict and execute, to the point where we're worrying that hangings will increase because there are too many people on death row. We say that we retain this policy as a deterrence, yet information about the death penalty is kept hush-hush and the local media barely touches the subject, keeping Singaporeans in the dark about its use.

I am writing this issue in anger, in grief, in exhaustion. There has already been too much anxiety, too much fear, too much pain and trauma, and none of this is helping people who need support, treatment and environments in which they can thrive. People are being killed for a state narrative that is not true. It's not just frustrating. It's grotesque, and the fact that it's being done in all our names makes us grostesque too.

Still, I write this issue because I know we aren't helpless. Singapore's capital punishment regime operates on our behalf, which means we have a right to say something about it, to work towards pulling it down and chucking its bloodstained ruins into the dustbin of history.

If this is something that troubles you, if you think people like Rosman and Pausi and Roslan and Nagen and Syed and Fadzir and Pannir shouldn't be put to death, if you think no one should be hanged by the state at all — please write to your elected representatives and express your concerns. Go to the Meet-the-People Sessions and tell them to their faces. Post letters to the President, or hand deliver them to the Istana, to add your voice to clemency pleas for these men. Start petitions, sign petitions, write Facebook posts, send tweets, make Tiktoks, talk live on Instagram. Bring the subject up when you're out with your friends, when you're sitting down with your families. Do anything and everything you can think of to talk about this issue so that more people know about it. Not everyone will agree with us, but the more we talk about this on multiple platforms and in multiple spaces, the more entry points we provide for people to engage and consider this issue, and perhaps join us in this fight.

As I mentioned at the start of this issue, capital punishment is not something that the local mainstream media seems keen to cover in detail. That means it's left up to us to talk about it, to amplify the stories we hear and spread awareness and education from one to another however we can.

The people on death row count on their lawyers, their families, their friends, activists and NGOs to do whatever can be done to save them from the gallows. They're also counting on you.

Thank you for reading this special issue instead of the regular weekly wrap. Please feel free to share this widely — forward this email to everyone you know, share the URL on social media, anything!