The following is based on observations made and research done in the course of campaigning against the death penalty and working with the families of death row inmates, which I have been doing since 2010.

Efforts have been made over the years to verify information, but given the scarcity of publicly available data, this is always a challenge. If there are any inaccuracies, I’d be happy to correct or clarify them. I urge the government to make more information related the use of the death penalty in Singapore publicly accessible.

FIRST PUBLISHED: 18 September 2020

UPDATED: 16 August 2022

First, the basics

What offences are punishable by death in Singapore?

The death penalty is on the books as a punishment for a multitude of offences in Singapore, but it’s generally used for three main ones (in this order): drug trafficking, murder, and firearms offences.

Since the vast majority of death row cases in Singapore have to do with drug offences, the rest of this piece will focus on the death penalty for drugs.

Are Singaporeans in favour of the death penalty?

The Singapore government often points to their own surveys indicating widespread support for the death penalty. However, so far the only independent and comprehensive study of public opinion on the question of capital punishment was a survey conducted in 2016 with 1,500 Singaporean respondents. This survey, using a questionnaire designed by criminologist Roger Hood, was conducted by academics Chan Wing Cheong (NUS), Tan Ern Ser (NUS) and Jack Tsen-Ta Lee (SMU), alongside Braema Mathi of human rights NGO Maruah.

The survey found that “Singaporeans apparently favoured the death penalty despite admitting that they knew very little about it, was not interested in it and could not give an accurate estimate of the number of persons executed.” The researchers also noted that support for capital punishment in Singapore is “not as strong as it appears”:

“There was a much lower support for the death penalty when respondents were faced with scenarios of cases—all of which would have merited the mandatory sentence under the current Singapore law—than the proportion who said they favoured it in the abstract. This was particularly so for drug trafficking and firearm offences.”

The survey also found than less than half the number of respondents were in favour of the mandatory death penalty for drugs. This is significant, because the majority of prisoners on death row received the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking.

How many people are executed every year?

The Singapore Prison Service publishes the number of executions carried out in its annual reports. There were no executions carried out in 2020 and 2021, likely due to challenges in court involving multiple people on death row. However, executions have resumed at an alarming pace in 2022. As of the time of writing, there have already been 10 executions (all for drug offences), out of 14 execution notices issued. (The remaining four received stays or respite orders due to legal intervention.)

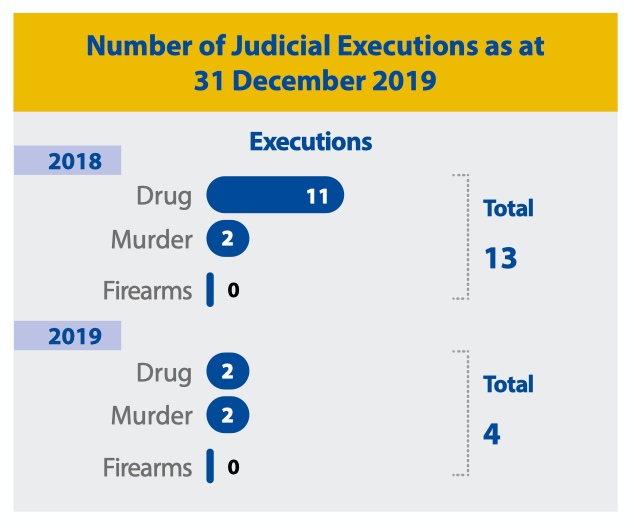

In 2019, four people were hanged (two for drug offences, and two for murder). There was a spike in 2018 and 13 people were hanged that year (11 for drug offences, and two for murder).

(Taken from the Singapore Prison Service’s 2019 annual report.)

What is the process like?

The general process for capital cases is as follows (there are, of course, variations from case to case, depending on the circumstances):

- After one is charged with a capital offence, the trial takes place in the High Court before a judge (Singapore abolished jury trials in 1969).

- If one is convicted by the High Court and sentenced to death, one is entitled to appeal the conviction and sentence at the Court of Appeal, which is the highest court in the land. A bench of three to five judges will hear the appeal, after which they can choose to uphold or overturn the decision of the lower court. The decision does not need to be unanimous: it is possible for a death sentence to be upheld by a 2-1 or 3-2 split among the appeal judges.

- If the Court of Appeal upholds the sentence, the individual has the option of appealing to the President for clemency. The President does not actually have discretion, but has to act on the advice of the Cabinet.

- If clemency is rejected, the prison authorities can then schedule the execution (after the President signs the order), which is carried out by long-drop hanging. Based on previous executions, this usually takes place around 6am. While hangings used to only be carried out on Fridays, we have seen in recent years (particularly in 2022) that executions can now be carried out on other days of the week.

There is no independent body that oversees executions and publishes its findings, and therefore no data on whether executions have been botched in Singapore. Unlike the United States, family members, journalists and independent observers are not allowed to witness executions.

How is the death penalty for drugs imposed?

Under Section 17 of the Misuse of Drugs Act, if someone is found in possession of a certain amount of drugs as specified in the law (for example, 2g of heroin or 15g of cannabis), they are presumed to have those drugs for the purpose of trafficking, unless they can prove otherwise. Section 18(1) says that anyone proven to have custody of anything containing a controlled drug, or even the keys to premises or places containing a controlled drug, is presumed to have the drug in their possession, unless proven otherwise. Section 18(2) then goes on to say that, if it is proven or presumed that the drug is in one's possession, it is presumed that the person knew the nature of the drug unless it is proven otherwise.

If the amount of the controlled drug goes over another threshold (specified in the Second Schedule of the same law), such as 15g for heroin or 500g of cannabis, the offence carries the mandatory death penalty — this means that, as long as one is found guilty, the only penalty the judge can hand down is death.

In 2012, the government amended the Misuse of Drugs Act to make tweaks to this mandatory death penalty regime. These changes laid out specific and narrow circumstances in which the courts will be able to sentence someone to life imprisonment with caning, instead of death. These circumstances are:

- If the offender was only a drug courier (i.e. they have no other role except transporting drugs from one point to another), AND

- Was suffering from an “abnormality of the mind” that “substantially impaired his mental responsibility for his acts”, OR

- Has received a Certificate of Substantive Assistance from the prosecution, certifying that they had “substantively assisted” the authorities in disrupting drug trafficking activities

While these amendments to the mandatory death penalty regime for drugs have allowed some accused persons to escape the gallows, they continue to be very problematic.

One of the most troubling aspects is the Certificate of Substantive Assistance system, as it’s unclear how the authorities make their decision whether or not to grant such a certificate.

There have been cases, such as that of Cheong Chun Yin, where the Attorney-General’s Chambers first refused to issue a certificate, only to change their minds later. In other cases, co-accused persons who both told the authorities what they knew found that one had been issued a Certificate, and the other not.

This certificate system essentially reduces the question of whether a human being should be given the chance to live to a consideration of how useful that person is to law enforcement. This was made abundantly clear in the case of Pannir Selvam Pranthanaman, whose application for a judicial review was dismissed on 26 November 2021. Although the AGC accepted that Pannir cooperated with the investigators and provided them with information, that information had not been "useful" because the Central Narcotics Bureau claimed to have already known about it and therefore did not have to "use" what he told them. Pannir was therefore not eligible for a certificate, which meant that the courts could only uphold his death sentence.

Another problem with this certificate system is that it is in essence a form of inducement that encourages people under interrogation to self-incriminate. An individual being questioned for a drug trafficking offence is left to make the difficult choice between offering as much information as they can in the hopes of being able to obtain a Certificate of Substantive Assistance — while likely also self-incriminating and undermining any defence they might later present — or remaining silent, and losing their chance to escape the gallows should they be found guilty. As individuals do not have access to legal counsel during interrogation, this is a difficult decision that has to be made without legal advice.

What is death row like? Who is on death row?

There isn’t much public information about death row conditions. Prison officers, executioners, and counsellors are bound by the Official Secrets Act and therefore cannot speak publicly about what conditions on death row are like. There are currently over 50 people on death row in Singapore, with ethnic minorities disproportionately over-represented within this number.

From what activists have been able to gather, those on death row stay in single cells. Even when they have 'yard time', they are in rooms alone, although they might be able to speak with the person having yard time in the next room, through a mesh/screen that blocks their view. I’ve heard from some family members that the execution chamber is in the same part of the prison as death row — some of the men on death row say that they hear sounds coming from the execution chamber when someone is being hanged.

People on death row are usually allowed visits from family members once a week, for about 40 minutes to an hour each time. Prisoners and their families are usually given seven days' advance warning of an execution. During that final week, daily family visits are allowed, and for a longer period of time (about 10am–12pm, then 2pm–4pm). These visits take place behind a pane of glass; no contact is allowed. Usually, three visitors are allowed into the room at a time, so if one has a big family or many visitors, they will have to take turns.

When the borders were closed due to Covid-19, families not in Singapore were unable to visit their loved ones. The Malaysian family of Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam was only able to enter Singapore to visit him on death row after they received a notice of execution, and even that required overcoming numerous administrative hurdles. In place of visits, prisoners were given 30 minutes of phone calls every week. However, once the borders reopened, these phone calls were halted, even if the families were not yet able to travel to Singapore to visit.

Travelling to Singapore for prison visits

For non-Singaporean families, travelling to Singapore to visit their loved ones on death row can be a challenge for many reasons, from health concerns to financial woes. Many of these families are working class and cannot easily afford the travel expenses, especially when things are often so much more expensive in Singapore.

The Transformative Justice Collective, of which I'm a member, runs a Support Fund that helps families with these expenses (among other things). You can find out more about the Support Fund here.

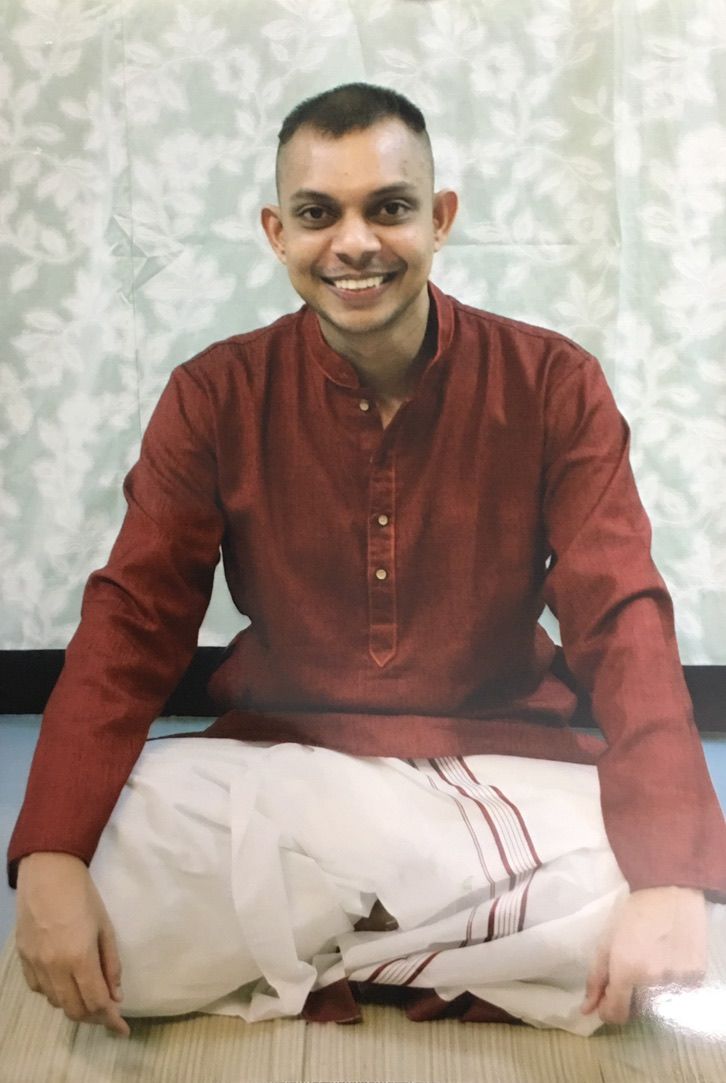

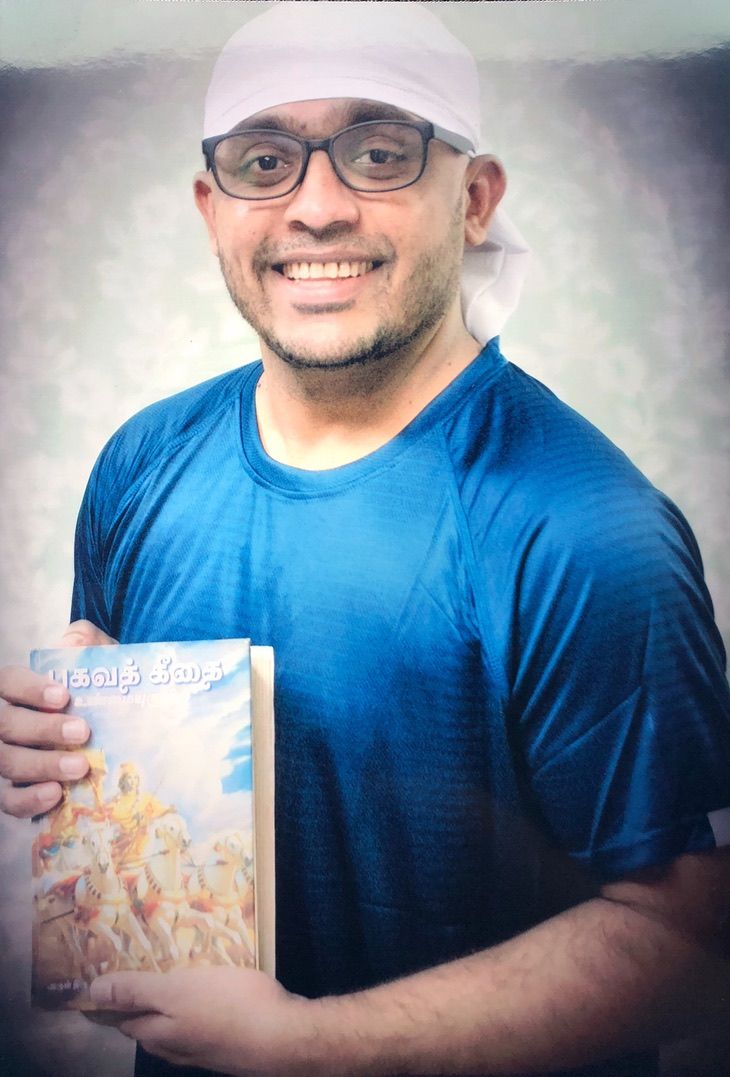

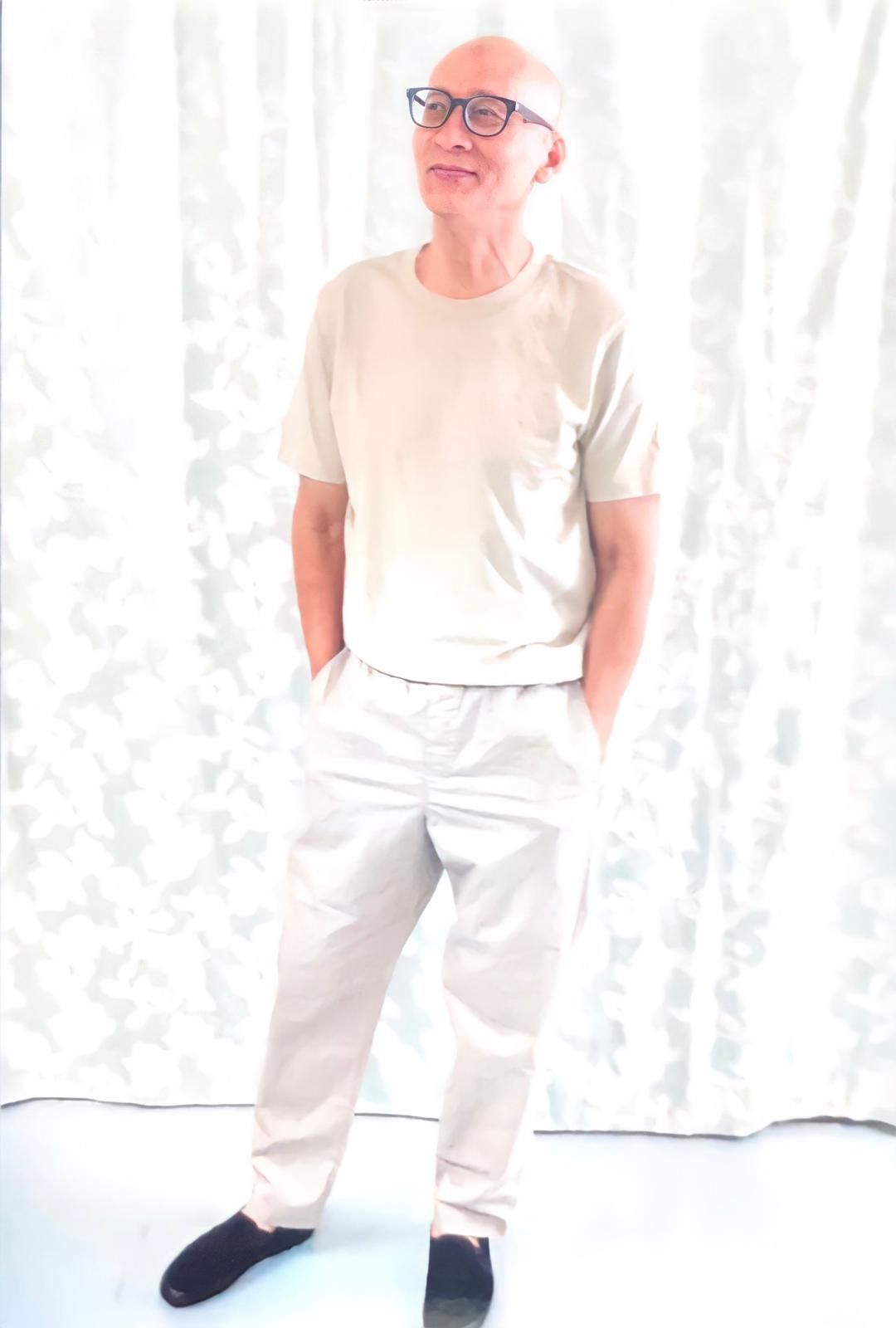

At some point in the week before their execution, the inmate is allowed to change into different outfits — provided by their family — and pose for photos. These portrait photos are given to the family as keepsakes.

Frequently Heard

The following are common responses that I’ve come across over the years, accompanied by my responses/counter-arguments.

“This is the law, and everyone knows about this.”

The first thing to keep in mind: laws are man-made. Laws can be unjust, get out-dated, and be amended. History is full of laws that were enforced for years, only to be changed or repealed as society evolved, or as injustices were righted. Singapore itself made amendments to the death penalty regime following a review in 2012 — there are people who were hanged prior to 2012 who might have been spared the gallows under these amendments.

Just because something is legal or enshrined in the law does not automatically make it ethical, moral, right, or just. When talking about the death penalty, it isn’t enough to say “it’s the law” — we should also ask ourselves if the offence is one that is deserving of death, and why we think that.

We also need to ask ourselves if a country’s criminal justice system should be given the power to decide who lives and who dies. We should ask: What exactly does the death penalty achieve? Who does it help? What does it say about our society? What do we want “justice” to be about?

There are many reasons and factors behind the choices people make. These could be related to upbringing, socioeconomic circumstances, psychosocial disabilities, financial pressures, past trauma, and many others. It’s easy for us to judge someone based on our own experiences (which could be very different from theirs) and conclude that they were irrational, stupid, untrustworthy, or undeserving. But when the penalty is as harsh and irreversible as death, we must be careful not to pass judgment on others too easily or too quickly.

And all this is even before we consider the very important, very scary, and (worst of all) very likely possibility of wrongful executions. No legal or criminal justice system is perfect, and mistakes are bound to occur in both capital and non-capital cases. In non-capital cases, these mistakes can be addressed by releasing the individual from prison and sometimes even by paying compensation. In capital cases, however, there would be no way to bring back the individual from the grave.

In September 2020, the Court of Appeal overturned their own decision and acquitted Ilechukwu Uchechukwu Chukwudi of drug trafficking, setting him free. The appeal court had previously convicted him of trafficking drugs, saying that he had made “numerous lies and omissions” in his statements to the Central Narcotics Bureau. However, his pro bono lawyers persisted and managed to get the case reviewed again (no easy feat), whereupon it was found that Ilechukwu was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, which could have explained his behaviour during investigation, making it “unsafe to draw any adverse inference against him from his lies and omissions.”

If Ilechukwu’s lawyers hadn’t persisted, he could have been sentenced to death (or at the very least life imprisonment with caning), and been at risk of execution. He’s the second Nigerian in as many years to be acquitted of a capital offence related to drugs in Singapore: last year, Adili Chibuike Ejike walked free after spending over two years on death row.

Here’s a short clip of a debate on whether capital punishment should return to the United Kingdom that touches on the point of wrongful executions:

(This video is from BBC Question Time. Ian Hislop, the editor of Private Eye, is debating capital punishment with Priti Patel, who is currently the UK's Home Secretary.)

“Singapore’s capital punishment regime keeps us safe, unlike other countries with higher rates of crime.”

While Singapore has a lower crime rate than various other jurisdictions, there’s no evidence proving that this is due to the death penalty. Remember: correlation does not mean causation! There are many other variables that come into play, such as education, socio-economic status, community support, quality of law enforcement, etc.

We should also ask ourselves: safe from what? There’s no evidence that the death penalty works better than any other punishment in deterring crime. While most of the research has been done in relation to homicide — including a study comparing the murder rates of Hong Kong (no death penalty) and Singapore (death penalty) — when it comes to studying capital punishment’s impact on drug-related crime, it becomes much more complicated, as pointed out by Harm Reduction International:

“A plethora of indicators could be used to consider deterrence with drugs. Might it be arrests for drug offences? Representation of drug offenders in the prison population? Hospital admissions for drug-related issues? Overdose statistics (which can be brought down anyway with simple and cheap harm reduction interventions)? Moreover, which drugs: marijuana, cocaine, heroin, so-called ‘party drugs’ like ecstasy? Would a reduction in arrests for marijuana represent a successful indicator for all drugs? Trying to prove or disprove the deterrent value of drug laws is extraordinarily difficult. Anecdotally, one could say harsh drug laws do not work. For example, Iran has some of the toughest drug laws in the world and a high prevalence of injection drug use. Sweden does not have the death penalty and it has comparatively low rates of problematic drug use.”

Oxford professors Roger Hood and Carolyn Hoyle wrote in their book, The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective, that in all the countries — including Singapore — that retain capital punishment for drug offences, “it has been argued that the death penalty is an indisputable deterrent to drug trafficking, but no evidence of a statistical kind has been forthcoming to support this contention”.

What we do know, however, is that the death penalty has been used against people from disadvantaged or marginalised backgrounds, people struggling with addiction, and even against people with borderline IQ.

Thank you for reading Tochi's story yesterday.

— Kirsten Han 韩俐颖 (@kixes) September 25, 2020

Today I'd like to talk about Rozman bin Jusoh, a Malaysian arrested in #Singapore in 1993. He was 22 years old.

He was charged w/ trafficking 1040.8g + 943.3g of cannabis. Under the law, 500g or more = mandatory #deathpenalty.

“What about the victims? Drugs destroy lives and families — why are we pleading for traffickers instead of the victims?”

This is a common concern, and a fair one — we should be concerned about those whose lives have been negatively affected by drug use and abuse. But given that there’s no evidence the death penalty actually deters or reduces drug trafficking (see above), it’s unclear how the death penalty actually helps people struggling with addiction, or those affected by their behaviour.

It’s also wrong to imagine that “traffickers”, “addicts”, and “victims” are mutually exclusive categories. The lines are often not so clear. Sometimes those who are caught and charged as traffickers are themselves struggling with drug dependency (especially given the presumption clauses within the Misuse of Drugs Act). Abdul Kahar bin Othman and Nazeri bin Lajim are good examples of this. Instead of helping people overcome their dependency on drugs, the death penalty sometimes actually kills them.

Abolitionists don’t campaign against the death penalty because we don’t care for people who have suffered from drug addiction and abuse. Instead, we argue that society has to approach the issue in a holistic way that focuses on support, rehabilitation, and reintegration into society, rather than punishment. We believe that we need to make changes in society that make it more equal and provide conditions that protect people from being easily exploited. We believe that addiction should be predominantly treated as a public health issue, and not a criminal one. We believe that compulsory drug detention centres — described by some as “jail with a different name” — don't actually provide the support and treatment that people with drug dependence actually need. We also emphasise the importance of dismantling prejudice and stigma in society against drug users and ex-offenders, so that they’ll have more support when trying to reintegrate and get their lives back on track. Harm reduction approaches, which emphasise care, solidarity, and respect for human rights, are much more effective than dehumanising punishments that end up causing more harm to individuals and society. Research conducted in Malaysia shows that people who go to voluntary treatment centres providing evidence-based treatment do not relapse as quickly as those sent to compulsory drug detention centres.

Furthermore, the families of people on death row — be they parents, partners, siblings, children, or other relatives and close friends — also become victims of the system. While they themselves haven’t been convicted of any crime, the death penalty puts them through significant emotional, mental, and often financial distress.

This Twitter thread provides an example of the anxiety that families and inmates can go through:

One of the most sickening things about the #deathpenalty is how cold and administrative is. I wrote about this in 2017, but have never felt like I've been able to convey the full horror of it: https://t.co/AgjH8ZTBRG Something that happened last night provides another example...

— Kirsten Han 韩俐颖 (@kixes) September 18, 2020

If we don’t execute them, then what?

Under the current system, the alternative to the death penalty for drugs is life imprisonment (generally with caning, itself also a very cruel and inhumane punishment).

Given the controversial yet fixed position of the capital punishment regime in Singapore (as well as broader restrictions on freedom of expression and dissent), Singaporeans have not yet had much opportunity or space to talk about alternatives to the status quo. But groups like the Transformative Justice Collective are committed to thinking and learning about transformative and restorative justice approaches, and creating space for such discussions.

When it comes to the death penalty for drugs, this is also a question of drug policy. Instead of just focusing on capital punishment, we also need much wider discussions about how Singapore treats drug use and drug users. We need more evidence-based information, instead of moral panic and finger-wagging. (Look at the section above!)

Why should we spend taxpayers’ money to feed and house these criminals in prison?

This is a question of values. Abolitionists believe that no matter what someone has done, we cannot reduce human life to dollars and cents. This is why the question “why should we pay to keep someone alive?” is a highly problematic one. As an anti-death penalty activist, I find it difficult to engage on these grounds, because it already signals a great disconnect in terms of personal values and beliefs.

That said, it’s not always the case that the death penalty is cheaper than keeping someone in prison, even if it’s for a long period of time. This has already been proven in the United States, where capital cases turn out to be far more expensive than other cases due to the number of appeals and challenges. There is insufficient data in Singapore to determine what the situation is here.

If we’re concerned about the death penalty, what can we do as Singaporeans?

It’s not easy to advocate against the death penalty, because it’s a very emotive issue, and, in Singapore, is also considered politically sensitive. Singapore’s government is very committed to the retention of the death penalty, and ministers have spoken in favour of capital punishment even on the international stage.

But this doesn’t mean that Singaporeans are helpless. As the public opinion survey indicates, most Singaporeans don’t know very much about capital punishment and how it is applied in our country, and, when faced with specifics, support for the death penalty falters or drops. This means that there is a great need for public education and awareness-raising, so that more people can be prompted to get informed and to consider their positions on the issue. Sharing articles, petitions, videos, and other resources on capital punishment, criminal justice, drug policy, and harm reduction can help reach more people and encourage them to think about where they stand. It also creates more and more space for Singaporeans to discuss this issue; the more we normalise talking about the death penalty, the more we can push it into the public eye.

Writing to Members of Parliament, the Cabinet, and the President is also very useful and important. Not only is it a way to practice taking action as engaged citizens, it also signals to those in power that the death penalty is an issue that Singaporeans pay attention to and care about. The more people speak out against the death penalty and let politicians know about it, the greater the political cost of arguing for the death penalty or executing someone.

Issues that were once neglected or ignored — such as migrant workers’ rights — have, over the years, slowly made its way into the public consciousness, prompting action. This can be done for capital punishment too, and every little bit of effort counts.

If you found this useful, please share!