Altering States is a secondary newsletter that I run within We, The Citizens, focused on drugs and drug policy. It's irregular and always free. When you subscribe, you can choose either We, The Citizens or Altering States or, better still, both!

Since it's Budget season, some of us at the Transformative Justice Collective decided to look at how much our government spends on fighting its war against (people who use) drugs. We published our post on Instagram here, but I figured I’ll take this opportunity to write a newsletter to show our workings and elaborate a little more.

Where we found the data

Every year when the Budget is delivered, the Ministry of Finance publishes the government’s revenue and expenditure estimates for the financial year on its website. It’s whopper of a document that they thankfully break down into more manageable PDFs. I’m most interested in “Expenditure Estimates by Head of Expenditure” because that’s where you find data on how much each ministry or state organ spent in the previous financial year and how much they estimate they will spend this financial year.

For this little project we zoomed in on the revenue and expenditure estimates of two ministries: the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF). Don’t forget to also look at the annexes where there’s more detail/information!

Punish versus Nourish

We set out to compare how much the government spends on punitive policies and programmes (Punish) versus programmes that provide social support and care (Nourish). We wanted to get an idea of the resources the government puts towards alleviating the difficult conditions that might contribute to people using drugs (as a way to self-medicate, escape from pain and trauma, to push themselves to work longer hours to make ends meet, etc.) versus the amount of resources dedicated to policing, surveilling, controlling and inflicting pain as “deterrent” punishment.

The challenge was how to determine what comes under “Punish” and what under “Nourish”.

“Punish” was a little more straightforward: look for spending on narcotics policing, prisons and mandatory drug detention. But it’s also more than that. What about the prosecutors at the Attorney-General’s Chambers who take on drug-related offences? What about the time and resources taken up in the courts for drug-related legal proceedings? These would also be financial costs linked to the war on drugs.

“Nourish” was complicated because it isn’t about just this or that programme—it’s about how our entire society is structured. It’s about how people experience life in Singapore. There are obvious things, of course, like how much we spend on harm reduction programmes for people who use drugs (an easy question to answer because we have zero internationally recognised harm reduction practices) but more fundamental are things that significantly impact individual well-being, stress and trauma. Factors like financial security, housing, work hours and conditions, access to universal/affordable healthcare (including mental healthcare) all come into play when we want to look holistically at drug use and drug dependence.

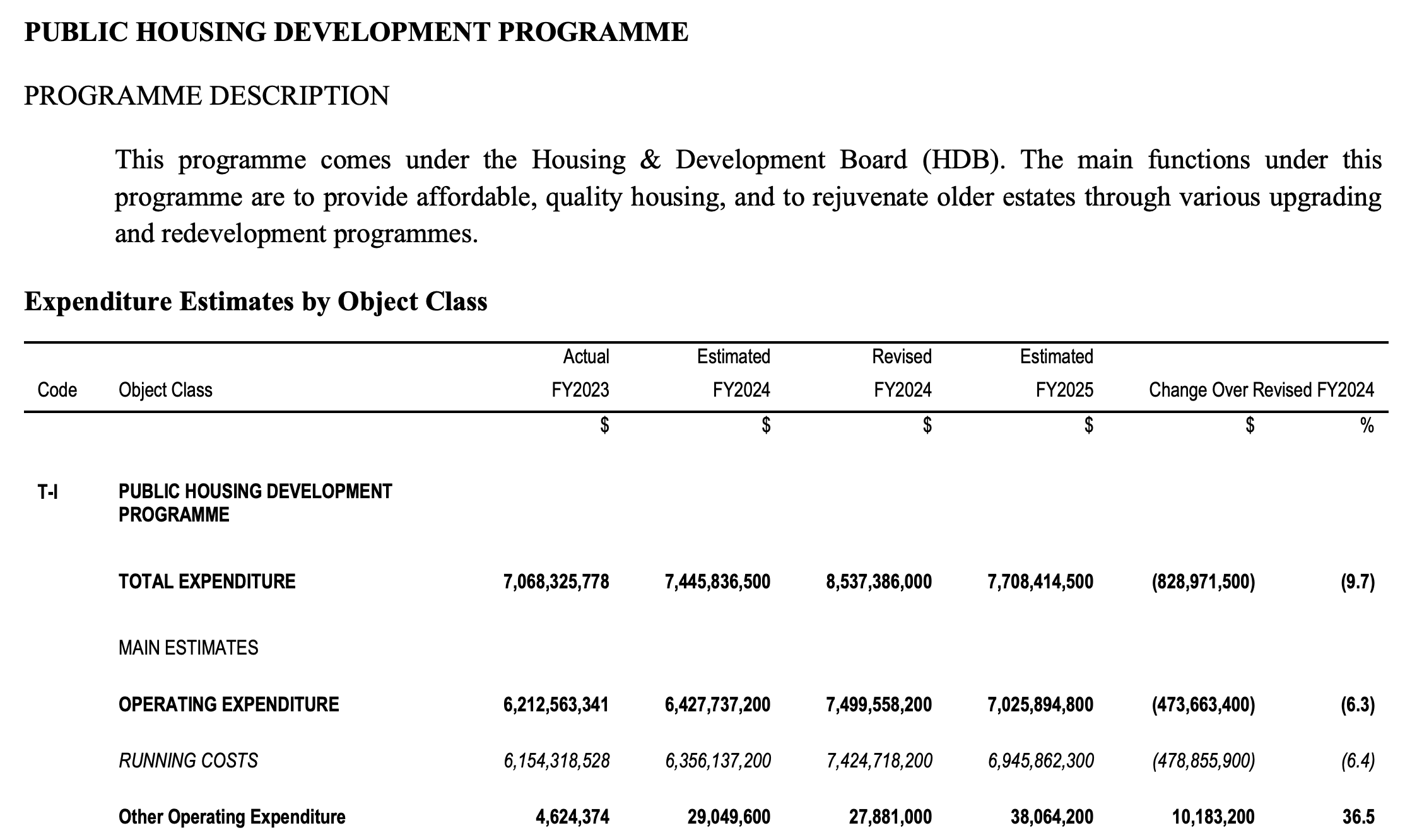

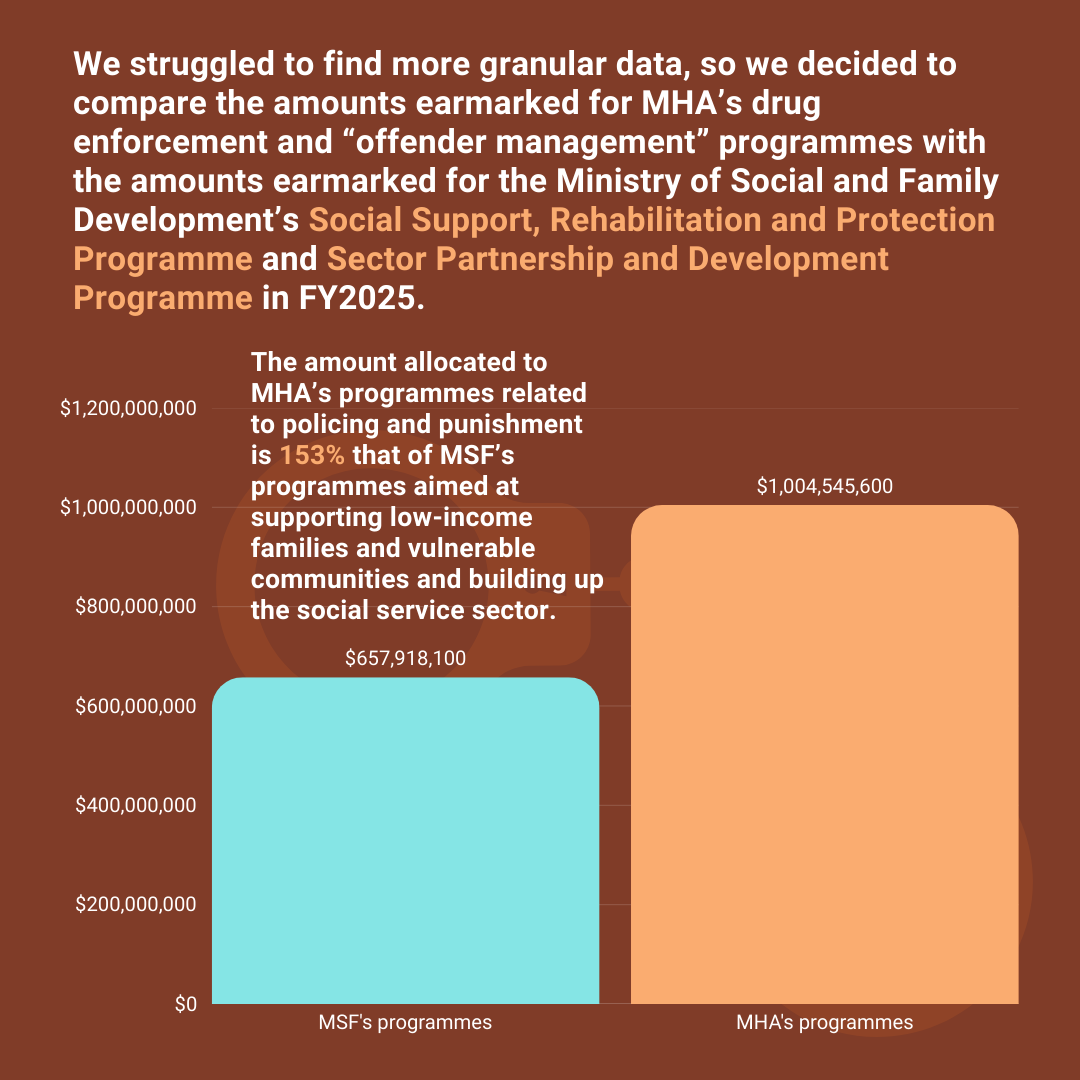

How should we calculate all this based on what's available in the Budget reports? We struggled to find the granular data we needed. For example, on the issue of housing, we looked at the Ministry of National Development’s expenditure estimates. While government ministers keep insisting that housing is totally affordable, mere mortals have a different experience. The Public Housing Development Programme (details in the annex), which is about providing “affordable, quality housing”, has a huge estimated budget of more than $7.7 billion for FY2025.

But most of that goes to operating expenditure and a lot of the development expenditure is actually for Select En-bloc Redevelopment Schemes (SERS) in various estates. We couldn’t figure out how much is actually spent on making sure that public housing is accessible and affordable even for the poorest among us. (It’s possible that this information isn’t in the MND report and maybe comes under some other ministry or somewhere else entirely.)

In the end, given the time and resources that our little band of volunteers had, we decided to keep it simple for now and go with the clearest indicators. This means we don't have exact figures but it at least allows us to start a conversation about how public funds are distributed.

MHA spends how much???!!!

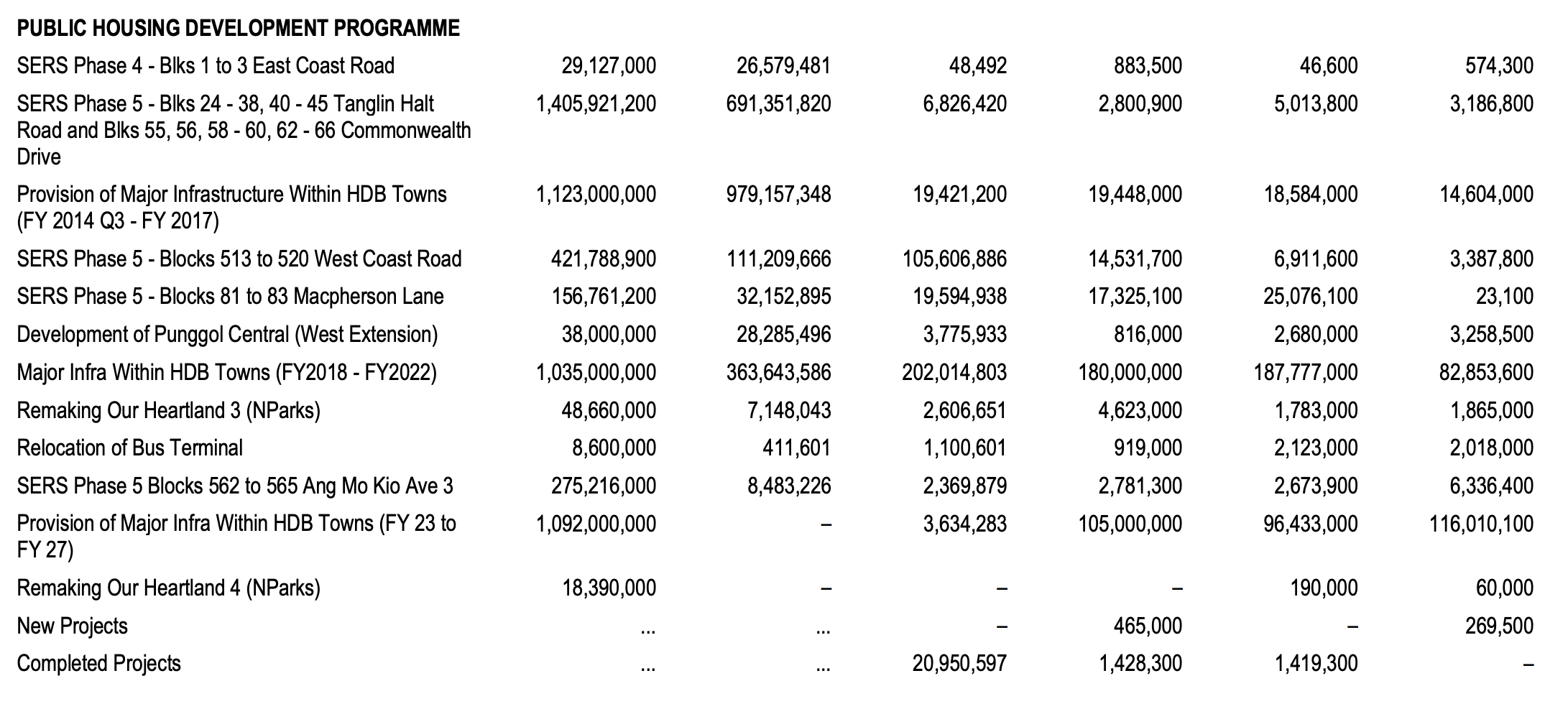

First up: MHA’s Drug Enforcement Programme.

This is the budget for the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB), which is not only in charge of drug-related policing but also Singapore’s overall approach to substances that have been made illegal. For example, public communications and “education” about drugs generally comes from the CNB, instead of, say, the Ministry of Health where one would expect the medical experts and healthcare practitioners to be.

Anyway… In FY2024, MHA spent $211,660,500, over $9.7 million more than estimated. For FY2025, they estimate that they’ll spend $215,379,100—an increase of more than $3.7 million from the previous year.

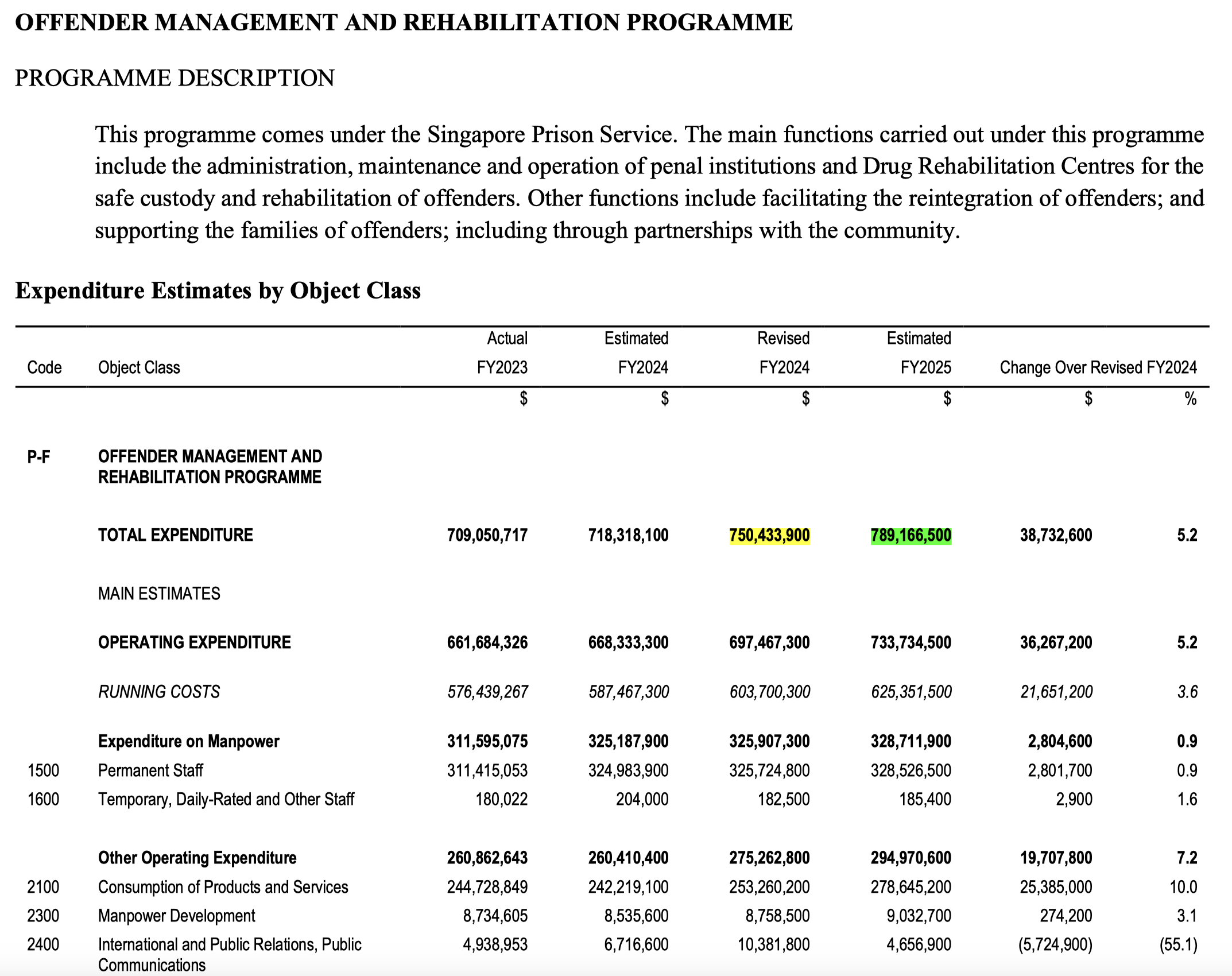

Next, we looked at the prisons budget or, as MHA calls it, the Offender Management and Rehabilitation Programme.

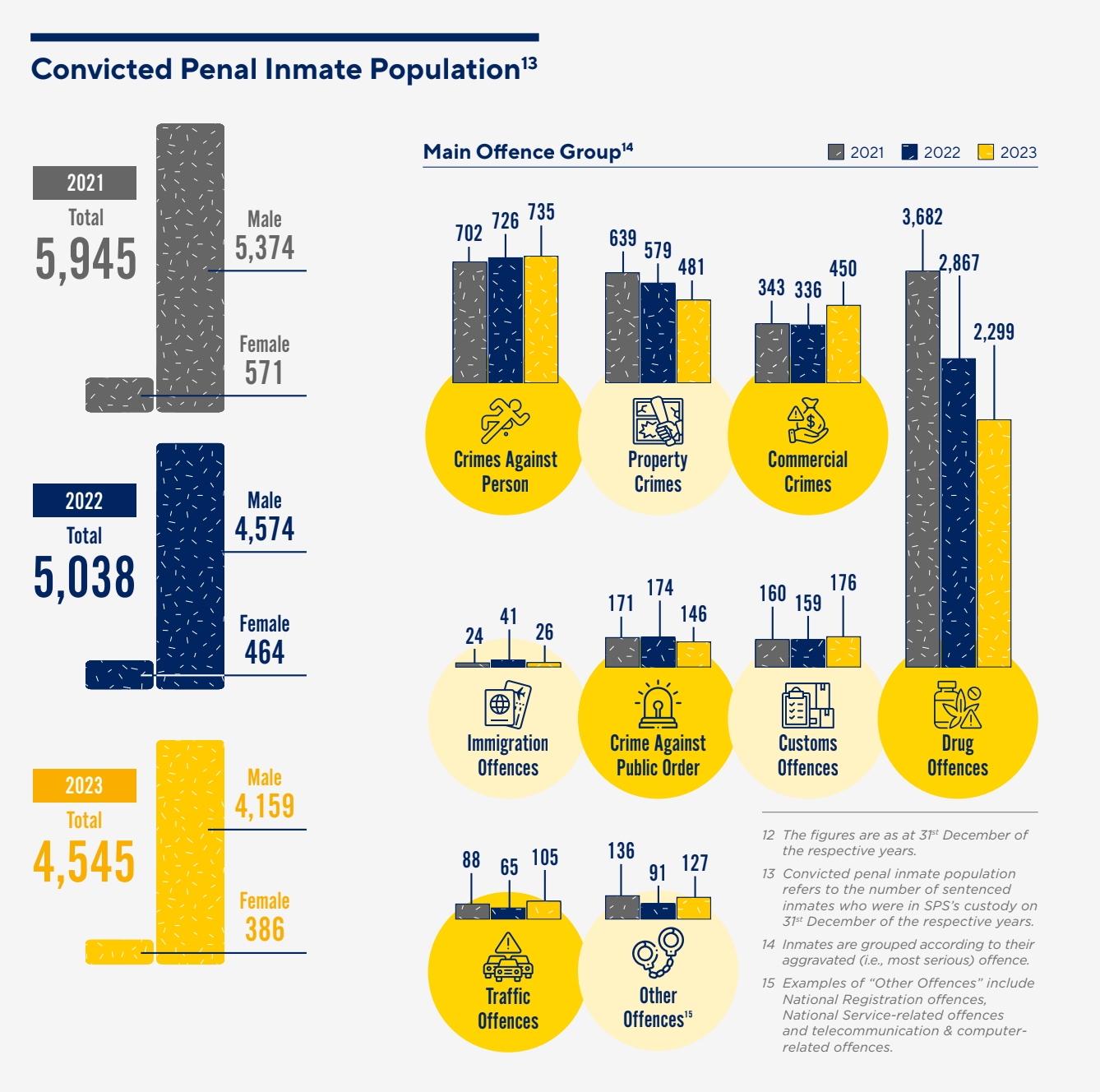

Not everyone in prison is there because of drugs. But a heck of a lot of them are. Statistics from the Singapore Prison Service show that drug offences form the largest category of incarcerated persons. While the number of people in prison for offences like “crimes against person”, “property crimes” or “crimes against public order” are in the hundreds for each category, the number of people in prison for drug offences is in the thousands. And then we have the Drug Rehabilitation Centres and those in remand (where, again, drug offences form the largest category). I think it’s safe to say that a sizeable chunk of the prison budget is related to the war on drugs.

In FY2024 MHA spent $750,433,900 on the Offender Management and Rehabilitation Programme, over $32 million more than estimated. For FY2025 they estimate they’ll spend about another $38.7 million more—a total of $789,166,500.

Is this a good distribution of resources?

For MSF, we looked at two things: the Social Support, Rehabilitation and Protection Programme, which is about helping lower-income families, vulnerable individuals and youth at risk, and the Sector Partnership and Development Programme, focused on building a “strong social service sector and a caring community”.

Both these programmes are getting a boost this year: a $71 million increase for the former to $438,794,000 and a $105 million increase for the latter to $219,124,100. In total, MSF expects to spend close to $658 million on both these programmes in FY2025.

Here’s the comparison:

While it’s good that MSF’s programmes are getting more funding this year, it still pales in comparison to what MHA has for drug enforcement and incarceration. This is despite clear evidence from around the world that the war on drugs has failed to eliminate, or even contain, the drug trade and that such punitive policies put people at more risk because prohibition means these black market substances aren’t subject to testing or regulation like other foods and drugs are, we can’t provide education on safer use and people who use are terrified of seeking help lest they get reported to law enforcement.

The ‘War on Drugs’ destroyed lives and damaged communities. Criminalisation and prohibition have failed to reduce drug use and deter drug-related crimes. We need new approaches prioritising health, dignity and inclusion, guided by the Int.Guidelines onHuman Rights & Drug Policy. pic.twitter.com/WbRPaSWZGk

— Volker Türk (@volker_turk) December 5, 2024

There are indications that even after half a century since we introduced the mandatory death penalty for drugs, Singapore’s not winning the war on drugs. In February 2023 MHA said in a press statement that

CNB has observed in recent years that syndicates are willing to deal in larger quantities of controlled drugs in each transaction. This shift may correlate with abusers purchasing larger quantities of drugs in a single transaction, instead of multiple smaller quantity purchases.

Why might someone purchase larger quantities of drugs?

One of the reasons why someone might buy a larger quantity of drugs at one go is the war on drugs. Because of harsh policing and punishment, a person who uses drugs might try to reduce the risk of getting caught in the middle of a transaction with their dealer by buying more in a single purchase so they don't have to meet up as often.

In February 2024 it was reported that the number of people arrested for using cannabis had hit a ten-year high. This year, it was reported that the two-year recidivism rate for people in DRCs is the highest it's been since 2015. Our response to this never seems to be to ask why people choose to use drugs, nor do we try to seek clarity about what would really protect the health and well-being of the maximum number of people. Instead, we just keep defaulting to deterrent punishments and moral panic-inducing propaganda campaigns.

Decades and billions of dollars later—with thousands of people either put to death, dead of overdose or with lives and relationships wrecked by incarceration and stigma—surely it's time for a different approach?

So what now?

As mentioned earlier, these are not exact calculations, just rough indicators. I'll admit that, as I posted the slides on Instagram and write this newsletter, I'm wondering if I'm going to get POFMAed because I haven't included this or that or interpreted the data the government's preferred way. But this is an important subject to raise because, with no political party willing to challenge our current drug policy, it's unlikely we'll hear much about this in Parliament. It's crucial that Singaporeans know about the significant resources we're pouring into punishment and ask ourselves if this is really protecting us and helping us thrive.

A lot more data is needed for further research and study. For example, how much do we spend on treatment programmes for people who use drugs while they're incarcerated? What sort of healthcare and mental healthcare is available to people who use drugs, especially those from working class communities who can't afford to go private for things like rehab and therapy?

While there's a dearth of information in Singapore, research and practice from elsewhere suggest that harm reduction is more effective (in terms of outcome and cost) than the war on drugs. This is something I and the other volunteers at TJC would like to look into soon—so watch this space!

Thank you for reading! As mentioned above, Altering States will always be free to access, so please share this with anyone who you think might be interested.