I'm sorry that there's no weekly wrap on Saturday morning again this week; I just arrived back in Singapore to a flurry of emails and text messages about Tangaraju's upcoming execution, so I haven't had any time to write the wrap tonight.

That said, I wrote this piece about rule of law, due process and fair trials on the plane. I thought of sharing it privately to INGOs and lawyer-y organisations at first (which is why it's written in this open letter-like form), but figured that I might as well send it out as a newsletter because these are important matters that more people should be aware of. So feel free to share this piece with your networks!

My name is Kirsten Han, and I come from Singapore. I work as an independent journalist in my home country, with a particular focus on politics, democracy, human rights and social justice issues. I have also been active as an anti-death penalty activist, volunteering and working in solidarity with the families of people on death row, for the past 13 years.

I am writing this because, while there are many legal professional organisations, surveys and reports that attempt to reflect the state of rule of law, due process and justice in jurisdictions around the world, I don't think there is widespread knowledge of serious problems in precisely these areas in Singapore.

My motivation for writing this now is because, on 19 April 2023, the family of Tangaraju s/o Suppiah, a 46-year-old Tamil Singaporean man, received a notice from the Singapore Prison Service informing them that his hanging has been scheduled for Wednesday, 26 April 2023. This is the first execution notice issued in Singapore in 2023, but last year we saw 15 execution notices issued to death row prisoners convicted of drug trafficking. Eleven of those men are now dead. They are among around 500 people who have been hanged in Singapore since 1990, most of them for non-violent drug offences. It is in blatant violation of international law, which states that the death penalty, if used at all, should only be reserved for the “most serious crimes”.

Much of this horror stems from government policy — including that of a brutal war on drugs — but there are also serious issues with access to justice and fairness, and Tangaraju’s case illustrates these problems very clearly.

Lack of timely access to legal counsel

In Singapore, one has a right to counsel, but only within an ambiguous “reasonable time”, which usually means that you only get to speak to a lawyer and seek legal advice once the police are done with their interrogations and investigations. With capital cases, it is common to see multiple statements recorded from a suspect or accused person, all without the presence of legal counsel or adequate information about their legal rights. This puts the individual at a severe disadvantage; even more so when the stakes are as high as life and death.

This was the case with Tangaraju, who was questioned by the police without legal counsel. (He is far from the only one — last year we even saw a 19-year-old boy, accused of murder, denied permission to speak with his lawyer because the prosecution claimed that it was "premature" for him to have access to legal counsel.)

Inadequate access to professional interpretation

To make matters worse, Tangaraju said that he had asked for a Tamil interpreter when the police were recording his statement, but his request was denied. Because of this, he said that he had trouble understanding his statement when it was read back to him. The High Court judge characterised this claim as "disingenuous" because Tangaraju had only raised this during cross-examination and had not asked again for an interpreter when subsequent statements were recorded.

Tangaraju had a Tamil interpreter during his trial, but was unhappy with the quality of interpretation.

Issues with recording statements

As far as we know, the interrogations of people who might be facing capital charges are not recorded (either video or audio). Instead, the individual’s answers are typed out by the investigating officers, and there is no requirement for these statements to be verbatim. Police officers routinely paraphrase answers given during interrogation — I can attest to this from personal experience of having been questioned by the police on three separate occasions between 2017 and 2022 for either my activist or journalist work. It is up to the individual being questioned to check, clarify or amend the recorded statement before signing off on it. Once signed, it is taken that the individual agrees that the statement is accurate. It is an offence to refuse to sign the statement. Individuals are not provided with a copy of their statement.

This is a challenge for any layperson at any time, but the difficulty was exacerbated for someone like Tangaraju, who not only had to deal with the stress and fear of facing a capital charge, but also struggle through the questioning without both a lawyer and an interpreter. Given that he said he was unable to properly understand the statement when it was read back to him in English, how could he have been in a position to make clarifications or amendments — with consideration for legal implications — before he was required to sign it?

Questions about evidence

Tangaraju was charged with abetting by conspiracy to traffic 1,017.9g of cannabis into Singapore. He was accused of having conspired with Mogan Valo, who had been arrested in possession of the cannabis in September 2013. However, Tangaraju has never handled the drugs that he allegedly tried to traffic.

Tangaraju is tied to the trafficking offence via two mobile phone numbers that are said to belong to him. He was already in remand for a separate offence by the time he was linked to this offence in March 2014, around six months after the arrest of Mogan Valo and another man, Suresh. Both Mogan and Suresh gave evidence that the two phone numbers they had saved in their mobile phones — one of which Mogan had used to coordinate the delivery of the cannabis — belonged to Tangaraju. Tangaraju was already in custody and his mobile phones were never recovered for analysis.

As an abolitionist, I am against capital punishment in all circumstances. But if states insist on retaining the death penalty, then there needs to be the highest standards of due process, evidence, and proof beyond reasonable doubt. The evidence against Tangaraju is so frighteningly thin. As my TJC colleague Kokila Annamalai told Vice World News, “There is such a high risk that this is an unsafe conviction.”

(Mogan, who gave evidence implicating Tangaraju, was charged with possession of the purposes of trafficking not less than 499.99g of cannabis. This is 0.01g below the 500g threshold that would attract the mandatory death penalty for trafficking cannabis, so it's likely an act of prosecutorial discretion not to charge him with a capital offence. Mogan plead guilty and was sentenced to 23 years imprisonment with 15 strokes of the cane.)

Challenges with legal representation and access to justice post-appeal

In Singapore, accused persons facing capital charges who can't afford to hire a lawyer can have legal counsel appointed for them via the Legal Aid Scheme for Capital Offences (LASCO) scheme. However, this scheme only recognises the individual’s right to a lawyer at trial and appeal, rather than throughout their encounter with the criminal justice system, from point of arrest to execution. As Sara Kowal of the Capital Punishment Justice Project wrote last year (in relation to Singapore's execution spree): "To be meaningful, [the right to legal counsel] must be afforded to the accused from the very start of a police investigation until a condemned person is literally led to the gallows."

In recent years we have seen many instances in which prisoners who filed applications seeking review of their cases post-appeal are accused of abusing court process. Lawyers who represented some of these prisoners have been fined for making such applications on behalf of their clients. The International Commission of Jurists called for an end to such punitive cost orders last year.

It has now become incredibly difficult — indeed, almost impossible — to find local lawyers willing to represent death row prisoners in post-appeal applications. This severely affects these prisoners' right to access to justice. In August 2022, 24 death row prisoners (Tangaraju among them) filed a joint application on this very point. They were left with no choice but to self-represent, and had to prepare for the case the best they could within an extremely tight and unusual timeline, as proceedings were sped up in light of the fact that one of their number was scheduled to be executed that week. A process that would normally have stretched for months was dispensed of within the week. A prisoner, Datchinamurthy a/l Kataiah, told the court that the prison had also not allowed them to meet to discuss their case together ahead of the hearings.

The Court of Appeal dismissed their application after deliberating for seven hours, during which the prisoners had to wait. Because of this, Abdul Rahim bin Shapiee missed his last meal before his execution.

Due to this troubling situation, multiple death row prisoners have had to self-represent in court. A couple of notable examples:

- A day before his scheduled hanging, the mother of Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam had to represent her son to plead for a stay of execution. Mdm Panchalai Supermaniam is in her 60s and works as a cleaner in Ipoh, Malaysia. She does not speak English. It was incredibly intimidating for her to stand before the Singapore Court of Appeal, across from state prosecutors, with only a court interpreter and a niece on her side. Mdm Panchalai was told that she was abusing court process, and her application was dismissed. The next day, the same day Nagaenthran was hanged, the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) issued a press statement again accusing Mdm Panchalai of abusing court process and suggesting that action for contempt of court might be taken against those who might have assisted her in filing the application. The AGC noted that the email address listed as a point of contact in the filing did not belong to Mdm Panchalai — the email address belonged to me, as Mdm Panchalai cannot read or write English, and would have been uncontactable that day while visiting her son in prison. The AGC published the email address in full in their press statement and, as a result, my email address was published in local mainstream media news reports.

- Nazeri bin Lajim, a 64-year-old Singaporean, had to represent himself in court the day before his execution. He pleaded with the court for more time, so that his family could continue their efforts to try to find him a lawyer. He also asked for more time so that more members of his large family would have time to visit him. His application was dismissed. One of the last things he said in court was that the judgment had been read out too quickly, and that, even with the assistance of a Malay interpreter, it was too complex and he could not really understand.

To make matters worse, in November 2022 the Parliament of Singapore passed new legislation that made it even more difficult to file post-appeal applications in capital cases.

In conclusion

Singapore has a dazzling international reputation. My country has consistently ranked highly in, among others, rule of law rankings. There is much admiration for our system, and we are often held up as a role model for others.

My interactions with people outside of my country have made me realise that many of the struggles and serious problems that we face on the ground are not well known or understood. This makes it difficult for human rights defenders and people like death row prisoners — who bear the brunt of the consequences of Singapore’s shortfalls when it comes to due process and access to justice — to receive solidarity and support, and for the government and institutions of Singapore to be held accountable for human rights abuses.

International reports, rankings, and endorsements carry weight. In writing this, I am not seeking intervention or meddling in my country’s domestic affairs or legal system, as my government might accuse me of doing (and it would not be the first time). I am merely asking that grave issues related to due process, fair trials and access to justice are recognised.

I make this appeal to the international community — particularly those of you who are committed to the rule of law, human rights and justice: praise my country for our successes if you must, but please remember to hold my government accountable for systemic failings and human rights abuses too.

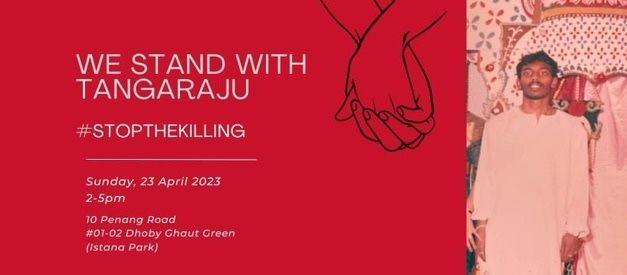

There will be a public event on Sunday at 2pm in the Visual Arts Centre on Dhoby Ghaut Green where Tangaraju's loved ones will speak and appeal for his execution to be halted and his case reviewed. We'll also be writing clemency appeal letters together. Please join us if you can.